Great Britain, in 1588, was the separate nations of England, Scotland and Ireland. It would not be until 1691 that England gained control of Ireland and 1707 that Parliament would unite England and Scotland to create Great Britain. In 1588, the separate - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 30

Title:

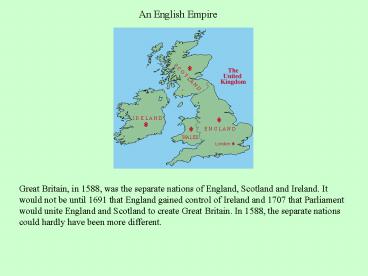

Great Britain, in 1588, was the separate nations of England, Scotland and Ireland. It would not be until 1691 that England gained control of Ireland and 1707 that Parliament would unite England and Scotland to create Great Britain. In 1588, the separate

Description:

An English Empire Great Britain, in 1588, was the separate nations of England, Scotland and Ireland. It would not be until 1691 that England gained control of Ireland ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:916

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Great Britain, in 1588, was the separate nations of England, Scotland and Ireland. It would not be until 1691 that England gained control of Ireland and 1707 that Parliament would unite England and Scotland to create Great Britain. In 1588, the separate

1

An English Empire

Great Britain, in 1588, was the separate nations

of England, Scotland and Ireland. It would not be

until 1691 that England gained control of Ireland

and 1707 that Parliament would unite England and

Scotland to create Great Britain. In 1588, the

separate nations could hardly have been more

different.

2

The House of Tudor had governed England for more

than 100 years. Under Queen Elizabeth I, it

enjoyed unprecedented peace and prosperity as it

morphed from a minor backwater island into a

dynamic commercial society.

Scotland, by contrast, was still half wild. Scots

managed their affairs with crude abandon, not

terribly unlike the events in Shakespeare's

Macbeth. This was the era of the sex-driven Mary

Stuart, Queen of Scots. Marys exploits

eventually caused the Scottish nobility to force

Mary to flee to England. Once in England, Mary

was imprisoned for conspiring to kill Queen

Elizabeth and in 1587, after 19 years in the

Tower of London, lost her head to the

executioner's axe. Scotland was further torn

apart by religious warfare as the Catholic

Stuarts and roughly half the population fought

the arch-Calvinist John Knox, founder of the

Presbyterian Church, and the other half of the

population.

3

England, for the most part, escaped religious

warfare in the 16th century. In 1547, King Henry

VIII split with the Catholic Church, but the

early English Reformation had little to do with

theology. The new church, the Church of England

(Anglican Church), was imposed from above. Much

of the liturgy remained the same, as did most of

the sacramental ritual. In this early Anglican

Church little was changed save that the king

became the religious head instead of the pope.

After King Henry's death, attempts were made to

reform the Anglican Church in a more Protestant

image, but their success was short-lived. In

1553, Henry's successor Edward VI died and was

replaced by Queen Mary Tudor, Bloody Mary, the

daughter of Henry and Catherine, and an arch

Catholic. She reunited England and Rome, burned

at the stake several hundred persons who dared to

protest, and married the dauphin of France and

when he died married the future King Philip II of

Spain. When she involved England in a losing war

with France, her reign was in jeopardy. She died

in 1558, before she could be overthrown.

4

Elizabeth I proved to be the only monarch of the

1500s able to handle the religious issue.

Elizabeth and Parliament worked out a compromise

to reorganize the Church of England. The new

church would outwardly mirror the Catholic Church

but would inwardly reflect Protestant dogma. All

citizens were required to attend public worship

in the national church, but no one's inner

conscience was publicly scrutinized. This system

worked until Elizabeth's death in 1603, when King

James I, a Stuart and a Catholic, restricted some

Protestant practices, particularly those of the

Scots Presbyterians. The system broke down when

James' successor, Charles I, went even further

and plunged England into civil war in the 1640s.

But until then England was religiously tranquil

enough to begin an era of prosperity and overseas

expansion.

5

English Economics, Exploration, and the Lost

Colony, 1496-1600

Although England was but a rather negligible

world power in the late fifteenth century, it

mustered enough resources to begin its own age of

exploration. In 1496, King Henry VII commissioned

the Genoese sea captain John Cabot, to seeke

out, discover, and find whatsoever isles,

countreys, regions, or provinces of the heathen

and infidels whatsover they be and to look for a

shorter sea route to Cathay (China). Cabot did

not find the Northwest Passage, but he did

discover the Grand Banks, a fishing region at the

edge of the continental shelf and claimed them

for England. Cabot was lost at sea on his second

voyage. His son, Sebastian, retraced Cabots

route and reached as far as the entrance into

Hudsons Bay

6

Enclosure Movement and the Crash of the Antwerp

Wool Market

In the sixteenth century, England underwent a

significant internal reorganization. As wool

prices rose, landowners began fencing land

(enclosing the land) to make more room for

grazing sheep. Englishmen greatly increased the

production of wool, channeling it through the

Antwerp Wool Market. Huge profits were made,

bringing more people into the market and

increasing production even more. By mid-century

England produced more wool than Europe could

consume. The price crashed in 1551. The collapse

of the market led English policymakers to search

for ways to avoid such economic disaster in the

future. They sought new markets as outlets of

wool and cloth. And to get more capital into the

economy, individual investors pooled their money

in proto-corporations, or joint-stock

companies. The Enclosure Movement forced poor

tenants off the large estates that had been their

home for centuries. Although population posed no

problem in England, the visible presence of

vagabonds and unemployed disturbed may powerful

Englishmen. Many believed that England was

over-populated and looked for some

outlet. European rivals, Spain and France, had

created colonies in the Caribbean and Florida

causing further concern in England. The three

elements (markets, surplus population, and

international rivalry) created a nexus that

provided the impulse for colonization.

7

English Motives for Colonizing

This westerne discoverie will be greately for

the inlargement of the gospell of Christe and

the refourmed relligion. This will yelde all the

commodities of Europe, Affrica, and Asia, as far

as wee were wonte to travell, and supply the

wantes of all our decayed trades. This will be

for manifolde imploymente of nombers of idle men.

This will be a great bridle to the Indies of the

kinge of Spaine and will be a means that one

or twoo hundred saile of his subjectes shippes

may go at fysshinge in Newfounde lande.

Richard Hakluyt

The key architects of this movement for

colonization were two cousins who became

prominent in the court of Queen Elizabeth, Walter

Raleigh and Richard Hakluyt. Raleigh provided the

money Hakluyt provided the reasoning. Hakluyts

Discourse of Western Planting, (1584) offers the

clearest expression of why England should create

colonies in the New World. The Oxford clergyman

wrote it to convince Queen Elizabeth I to grant

permission to colonize America. The book suggests

ways that colonies could benefit England (1) to

extend the reformed religion (2) to expand

trade (3) to provide England with needed

resources and markets (4) to enlarge the Queens

revenues and navy (5) to discover a Northwest

Passage to Asia and (6) to provide an outlet for

the growing English population.

8

Roanoke, The Lost Colony

Raleigh succeeded in winning a charter to

organize a private expedition to the area around

Albemarle Sound at Roanoke Island in 1585.

Raleighs 108-man team clashed with local

Indians, but they remained through the winter.

Hardship plagued the settlement, however, and in

the late spring the group packed up and returned

to England with Francis Drake when he happened

by.

9

A ship had already been sent to relieve the

first, but its eighteen men were killed in an

Indian attack. A second expedition landed off

Hatarask Island in July 1587. Led by Governor

John White, its 117 men, women, and children

resettled on Roanoke Island. White left the

settlers, including his granddaughter, Virginia

Dare (the first English child born in the New

World), and returned to England for supplies.

Before leaving, White carved the letters C.R.O.

into a tree and told the men to carve a cross

over them as a distress signal should they run

into trouble before he returned. He did not

return for three years because of the conflict

with Spain and the Spanish Armada. When White

reached the place of the settlement in 1590, no

one was there. He looked for a cross on the tree,

but found none. He found only the word Croatoan

carved into a post. Taking it to mean that the

mission had moved to Croatoan Island, he sailed

south in search of the settlers. He found no

English settlement on Croatoan or anywhere else.

War with Philip II of Spain during the 1590s kept

England from making another stab at colonizing

the New World until the early 1600s. No trace

of the Lost Colony of Roanoke has ever been found.

10

Jamestown

11

Queen Elizabeths death in 1603 did not interrupt

Britains pursuit of global power. King James I,

in 1606, granted charter to a joint-stock company

headed by Richard Hakluyt. The Virginia Company

of London, as it was known, divided the British

claims in North America with a rival company, the

Virginia Company of Plymouth. The original

charters had no western boundaries hence in

theory, they ran from the Atlantic to the

Pacific. The London Company was made up of

merchants and gentry from the west of England and

from London, itself. On December 20, 1606,

three ships, the Susan Constant (120 tons), the

Godspeed (40 tons), and the Discovery (20 tons)

left London with 144 passengers, under the

command of Captain Christopher Newport. The ships

briefly laid over at the Canary Islands and the

Bahamas, before arriving in Virginia at

Chesapeake Bay on April 26th with 104 survivors.

12

Following the orders of the London Company, and

after facing a brief conflict with the local

Indians, the Powhatan, the ships landed up the

newly-named James River and encamped at what

became Jamestown on May 13, 1607. Of the 104

survivors, 39 had noble titles and 36 more were

described as gentlemen. The others were

attendants, soldiers, and artisans skilled at

metalworkthat is to say, they were goldsmiths

and jewelers. Among the soldiers was a boorish

troublemaker of immense ego, Captain John Smith.

Smiths mouth more than once got him into trouble

with his commanders, as near the Canaries he was

accused of trying to foment a mutiny and so was

locked up for the rest of the voyage. When the

settlers unsealed their orders, however, they

found that Smith was named to the Council of the

Colony and put in command of the day-to-day

running of the settlement.

13

From the outset, the settlement was in trouble.

Located on the site of an abandoned Indian

village and in the Powhatan hunting grounds, it

continually faced Indian attack. Many of the

settlers refused to work. Instead they searched

for gold and left the chore of building shelter

to the soldiers. Instead of gathering or hunting

for food, many chose to steal it from the

Indians, causing no small amount of hostility.

The Indians, meanwhile, raided Jamestown to steal

weapons and gunpowder. Smith tried to force all

to work and, failing that, traded for Indian

maize. The English also gave Chief Powhatan a

formal coronation and made him an ally of King

James. This briefly improved relations with the

Indians, but did little to guarantee the success

of the colony, neither did the arrival of some

women to the community. Conditions hit bottom

during the winter of 1609-1610, after Smith

returned to England as a result of an illness.

That winter was known as the Starving Time.

Crop yields were miniscule because of a drought,

but there was still game in the woods and fish in

the river. Despite that, however, starvation

reduced the settlements population from nearly

500 down to 54 by the time a ship finally arrived

with fresh provisions and new settlers in May

1610. Shockingly, settlers had resorted to

cannibalism to survive. They dug up graves to eat

the remains. Equally shocking, the new Assistant

Governor recorded the settlers activities as he

sailed in. They were not out foraging for food in

the spring forests. They were bowling in the

street! Obviously, this settlement needed a

reworking.

14

Now we all found the losse of Captain Smith, yea

his greatest maligners could now curse his losse

as for corne, provision and contribution from the

Salvages, we had nothing but mortall wounds, with

clubs and arrowes as for our Hogs, hens Goats,

Sheepe, Horse, or what lived, our commanders,

officers Salvages daily consumed them, some

small proportions sometimes we tasted, till all

was devoured. . . . Of five hundred within six

moneths after Captain Smiths departure, there

remained not past sixtie men, women and children,

most miserable and poore creatures and those

were preserved for the most part, by roots,

herbes, acornes, walnuts, berries, now and then a

little fish they that had startch in these

extremities, made no small use of it yea even

the very skinnes of our horses. Nay, so great was

our famine, that a Salvage we slew, and burried,

the poorer sort tooke him up againe and eat him.

. . . And one amongst the rest did kill his wife,

powdered her, and had eaten part of her before it

was knowne, for which he was executed, as hee

well deserved now whether shee was better

roasted, boyled or carbonadod, I know not, but

of such a dish as powdered wife I never heard of.

This was that time, which still to this day we

called the starving time it were too vile to

say, and scarce to be beleeved, what we endured.

Q1. How does this vivid account by John Smith

compare with your previous sense of early life in

colonial Virginia? Q2. Who or what do you think

was to blame for the situation known as the

Starving Time?

15

In June 1610, Governor Lord De la Warr restored

order through a new code, the Lawes Divine,

Moral, and Martiall. All settlers were required

to work in work gangs under military discipline.

The day was divided by drumbeats 6 a.m. until 10

a.m. they worked in the fields. During the heat

of the day, they ate, did household chores, and

rested. They were back in the fields again from 2

p.m. til 4 p.m. If they still did not work hard

then they would be punished. Punishments were

also meted out for crimes, such as rape,

adultery, theft, lying, sacrilege, blasphemy,

killing a domestic animal, weeding a garden,

taking of a crop, and private trade. Anyone who

ran away from the settlement and was caught was

executed. The new rules helped save the colony,

but they still could not feed themselves. The

colony had still not found its purpose and the

London Companys investors were beginning to

wonder whether it had been worth it, particularly

after a new round of conflict with the Powhatan

emerged about 1611.

16

Eventually, an enterprising settler named John

Rolfe did find a profitable crop. Rolfe arrived

in Jamestown in May 1610 aboard Gates ship.

Rolfe had brought with him to Virginia some

Spanish tobacco plantings, hoping successfully to

cultivate them. By 1612, he gave his friends a

small sampling of his produce to see if it suited

their tastes. While not of the quality of Spanish

tobacco at the time, it was still palatable

enough for larger-scale cultivation. By 1617,

Virginia shipped 20,000 pounds of tobacco (at 3

shillings per pound) to England and the crop

became so profitable that if became known as

brown gold.

17

Rolfe also brought peace with the Indians. In

1614, the First Powhatan War ended when Rolfe

married the daughter of Chief Powhatan,

Pocahontas. In 1616, Rolfe, Pocahontas, and their

son traveled to England and Pocahontas met the

King. Tragically, just before they set sail to

return to the New World, the 22-year-old

Pocahontas died, likely of pneumonia. She is

buried in a churchyard at Gravesend.

18

With the colony saved, under new Governor Edwin

Sandys, the London Company created a new policy

for land distribution and to entice more

settlers. The headright system promised that

every new company shareholder who settled in

Virginia would get 50 acres of land for himself

and 50 acres for each family member he brought

over, including servants. Further to entice

settlement, the company a new constitution for

the colony, granting settlers the Rights of

Englishmen. In July 1619, Virginia created the

House of Burgesses, the first legislative

assembly in America. Its twenty-two members

represented their local settlements and governed

along with a Governor and executive council. Two

other events in 1619 further expanded the colony

(1) more women arrived as the company sponsored

the sale of women for wives 90 women were

bought for the princely sum of 125 pounds of

tobacco creating a better gender balance in the

colony (2) the first Africans arrived they

came on a Dutch trade ship, but were indentured

servants, not slaves. An indenture is a

contract. So, in return for the masters paying

their passage to the New World, an indentured

servant contracts to work for a specific term,

usually seven years. During that time the servant

has no rights to property. Upon completion of the

term, the servant is free to do whatever he or

she wishes and under Virginia law would receive a

headright of 50 acres.

19

The shift from a commodity-based company to a

realtor changed the London Companys relationship

with the colony. The companys new goal was to

get as many people to Virginia as possible. It

cared less about the condition of the settlers

when they got there and so the condition of the

colony suffered. Making matters worse, an Indian

war arose. Powhatans brother, Opechancanough,

seems never to have accepted the settlers or his

brothers peace. Upon his brothers death, in

March 1622, he led raids on the settlement that

turned into nearly two years of warfare and

killed 347 settlers, including John Rolfe. The

turmoil finally caused King James to appoint a

Royal Commission to investigate the Company. It

found that between 1607 and 1622 more than 14,000

people had emigrated to Virginia, but in 1624

only 1,132 of them still lived there. The

investigation forced James I to revoke the

Companys charter and make Virginia a Royal

Colony. Under the kings authority for most of

the remainder of the 1620s, Virginia stabilized

and slowly began to prosper.

20

Maryland

With settlements established in Virginia, other

Britons began to look at the Chesapeake region

for possible opportunities. As intolerance toward

Catholics increased in England, one family led

the charge for escape to religious freedom. In

1628-29, George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, visited

the Chesapeake region to check out its prospect

as a refuge for persecuted Catholics. He died

before winning a kings charter to the land, but

his son, Cecil Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore,

carried out the project. In 1632, King Charles I

granted all lands from the Potomac River north to

the Delaware River and a few hundred miles west

to the Appalachians to Calvert. In return for a

pledge of allegiance and a token payment of two

Indian arrowheads and a royalty of one-fifth of

any gold or silver discovered in the region,

Calvert could create whatever type of government

he chose, so long as any legislation was passed

with the Advice, Assent, and Approbation of the

Free-Men. This was to be the successful first

proprietary colony. Whereas the original colonies

were based on a charter granted to a joint-stock

company, and Virginia by 1624 had been turned

into a royal colony, Maryland was given to a

single man to do with whatever he chose.

21

Beginning in 1632, Calvert set up a recruiting

office for settlers and convinced about two

hundred settlers to join the first expedition. In

March 1634, Governor Leonard Calvert and the

other settlers established a settlement at St.

Mary's on a creek just north of the mouth of the

Potomac. Having learned from the mistakes of

Jamestown, they brought enough supplies to

sustain them. They also made sure they arrived

early enough in the year to plant a crop.

Finally, they were lucky to have friendly Indian

neighbors.

Saint Francis Xavier Church, Leonardtown, MD

Rebuilt on original site (1766)

22

Things went fairly well for the Calverts during

the 1630s in the early years of the colony, but

because he perceived that Catholics would likely

remain in a minority in the new colony, he

directed Leonard to establish a government based

on religious toleration. Religious questions

would not be part of public discourse. Land was

to be divided up based on a quasi-Feudal model.

Blood relatives of Calvert were to be granted

manors of 6000 acres. Manor lords would have

the power to adjudicate over local manor courts.

Lesser manors would consist of 3000 acres. The

rest of the population would be divided between a

tenant group and a small property-owning group.

Tenants would pay rent, either with labor or with

produce, and thereby sustain the lords. Small

farmers would be able to profit on their own

output. The land distribution plan did not

survive the first few years because of the

abundance of land and the dearth of labor. A few

years after the establishment of the colony,

manor lords were ordered by law to import labor

at first lords had to import five, then ten, and

eventually twenty laborers. In 1640, a

Virginia-style headright plan was imposed.

23

As Calvert expected, however, the settlers were

not Catholics. Indeed the hope for a religious

sanctuary was a failure. Puritans from Virginia

moved into the colony in large numbers. In the

1640s, as the Civil War raged between Puritans

and the Catholic King in England, religious

warfare erupted in Maryland. With Calvert's

death, in 1647, the Puritan William Stone became

governor. Tension continued until the passage of

the Maryland Act Concerning Religion (often

called, incorrectly, the Maryland Religious

Toleration Act) in 1649. The law guaranteed

religious toleration to all followers of Jesus

Christ and believers in the Trinity. It is

important to note, however, that the law promised

toleration only for Trinitarian Christians. Under

the Act, Jews and non-Trinitarian Christians

(Quakers, Unitarians) were not permitted freedom

of religion. The Act did, however, put an end to

the broader religious strife. With the good

chances for prosperity in tobacco production,

settlement increased. By the 1670s, the

population of Maryland neared 13,000, including

Catholic planters, Protestant farmers, indentured

servants, and a small but increasing number of

black slaves.

24

An Act Concerning Religion, Maryland 1649

Forasmuch as in a well governed and Christian

Common Wealth matters concerning Religion and the

honor of God ought in the first place to bee

taken, into serious consideracion and endeavoured

to bee settled, Be it therefore ordered and

enacted by the Right Honourable Cecilius Lord

Baron of Baltemore absolute Lord and Proprietary

of this Province with the advise and consent of

this Generall Assembly That whatsoever person

or persons within this Province and the Islands

thereunto belonging shall from henceforth

blaspheme God, that is Curse him, or deny our

Saviour Jesus Christ to bee the sonne of God, or

shall deny the holy Trinity the father sonne and

holy Ghost, or the Godhead of any of the said

Three persons of the Trinity or the Unity of the

Godhead, or shall use or utter any reproachfull

Speeches, words or language concerning the said

Holy Trinity, or any of the said three persons

thereof, shalbe punished with death and

confiscation or forfeiture of all his or her

lands and goods to the Lord Proprietary and his

heires. And bee it also Enacted by the Authority

and with the advise and assent aforesaid, That

whatsoever person or persons shall from

henceforth use or utter any reproachfull words or

Speeches concerning the blessed Virgin Mary the

Mother of our Saviour or the holy Apostles or

Evangelists or any of them shall in such case for

the first offence forfeit . . . the summe of five

pound Sterling or the value thereof in goods

and chattells, . . . but in case such Offender or

Offenders, shall not then have goods and

chattells sufficient to pay shalbe publiquely

whipt and bee imprisoned. . . . And that every

such Offender or Offenders for every second

offence shall forfeit tenne pound sterling or the

value thereof to bee levyed as aforesaid, or in

case such offender or Offenders shall not then

have goods and chattells within this Province

sufficient for that purpose then to bee

publiquely and severely whipt and imprisoned as

before is expressed. And that every person or

persons before mentioned offending herein the

third time, shall for such third Offence forfeit

all his lands and Goods and bee for ever banished

and expelled out of this Province. . . .

25

(No Transcript)

26

Chesapeake Society

How miserable that man is that governs a people

where six parts of seven at least are poor,

indebted, discontented, and armed. Governor

William Berkeley

In 1642, Governor William Berkeley arrived in

Virginia to begin thirty-four years of stable

governance. But colonizing was still no easy

task. Conditions had sufficiently improved to

make slavery a more viable economic choice.

Relations with the Indians, however, remained

difficult. In 1644, an elderly Opechancanough led

a second raid on the colony. It, too, killed

several hundred settlers, but this time, the

colonists were strong enough to retaliate with

great force. The raid was put down and

hostilities with the local Indians

ended. Tobacco production increased through the

1630s. But, ironically, it was so profitable that

so many settlers began planting tobacco that for

much of the period after 1650 it glutted the

market, causing the price to fall, and pushing

marginal farmers into severe debt. As the

population of poor grew and as the colony spread

deeper into the interior, above the falls at what

would become Richmond and toward the Blue Ridge

and up the Potomac, it became harder to govern

the colony. Adding to public displeasure was the

fact that Berkeleys government had become a

clique of family members and business relations.

The colonial treasurer was a Berkeley cousin, as

was the Secretary of State.

27

The discontent reached a head in 1675. Settlers

on the frontier believed the government was not

looking after their interests. In particular,

they thought it was not protecting them from

Indian attack as settlement moved west it came

into lands of different Indian tribes, notably

the Susquehanna. A minor squabble between

settlers and Indians along the Potomac turned

ugly and left nearly twenty-five Indians dead.

The Indians retaliated by attacking settlers

along the frontier and the James River. The

overseer of an up-river planter named Nathaniel

Bacon was killed in a raid. Berkeley proposed a

series of forts be built along the frontier, but

the assembly believed it would be too expensive

and besides what the settlers really wanted was

to get rid of the Indians and take their land.

Tensions grew.

28

In May 1676, Nathaniel Bacon led a group of

vigilantes against the Indians, despite

Berkeleys prohibition. Then Bacon and his men, a

collection of landless servants, small farmers,

and slaves, went on a rampage down river,

ultimately torching Jamestown itself. By October,

the rebellion was over, however, and Bacon was

dead, from malaria. Order was restored and

Berkeley had twenty-three of the rebels executed.

When news of the rebellion reached England,

Berkeley was recalled and a new regime was put in

place in Virginia, one that more clearly

protected the interests of common Virginians.

A peace treaty was made with the Indians who were

given reservations of protected land, leaving the

rest for development by colonials. By 1677, the

difficult infancy of Virginia ended. Now a

toddler, the colony would prosper.

29

Declaration of Nathaniel Bacon in the Name of

the People of Virginia, July 30, 1676

1. For having, upon specious pretenses of public

works, raised great unjust taxes upon the

commonalty for the advancement of private

favorites and other sinister ends, but no visible

effects in any measure adequate for not having,

during this long time of his government, in any

measure advanced this hopeful colony either by

fortifications, towns, or trade. 2. For having

abused and rendered contemptible the magistrates

of justice by advancing to places of judicature

scandalous and ignorant favorites. 3. For

having wronged his Majestys prerogative and

interest by assuming monopoly of the beaver trade

and for having in it unjust gain betrayed and

sold his Majestys country and the lives of his

loyal subjects to the barbarous heathen. 4. For

having protected, favored, and emboldened the

Indians against his Majestys loyal subjects,

never contriving, requiring, or appointing any

due or proper means of satisfaction for their

many invasions, robberies, and murders committed

upon us. 5. For having, when the army of

English was just upon the track of those Indians,

. . . and when we might with ease have destroyed

them who then were in open hostility, for then

having expressly countermanded and sent back our

army by passing his word for the peaceable

demeanor of the said Indians, who immediately

prosecuted their evil intentions, committing

horrid murders and robberies in all places, being

protected by the said engagement and word past of

him the said Sir William Berkeley . . . 6. And

lately, when, upon the loud outcries of blood,

the assembly had, with all care, raised and

framed an army for the preventing of further

mischief and safeguard of this his Majestys

colony.

30

7. For having, with only the privacy of some few

favorites without acquainting the people, only by

the alteration of a figure, forged a commission,

. . . against the consent of the people, for the

raising and effecting civil war and destruction .

. . 8. For the prevention of civil mischief and

ruin amongst ourselves while the barbarous enemy

in all places did invade, murder, and spoil us,

his Majestys most faithful subjects. Of this

and the aforesaid articles we accuse Sir William

Berkeley as guilty of each and every one of the

same, and as one who has traitorously attempted,

violated, and injured his Majestys interest here

by a loss of a great part of this his colony and

many of his faithful loyal subjects by him

betrayed and in a barbarous and shameful manner

exposed to the incursions and murder of the

heathen. And we do further declare these the

ensuing persons in this list to have been his

wicked and pernicious councilors, confederates,

aiders, and assisters against the commonalty in

these our civil commotions Sir Henry Chichley,

William Claiburne Junior, Lieut. Coll.

Christopher Wormeley, Thomas Hawkins, William

Sherwood, Phillip Ludwell, John Page Clerke,

Robert Beverley, John Cluffe Clerke, Richard Lee,

John West, Thomas Ballard, Hubert Farrell,

William Cole, Thomas Reade, Richard Whitacre,

Matthew Kempe, Nicholas Spencer, Joseph Bridger

And we do further demand that the said Sir

William Berkeley with all the persons in this

list be forthwith delivered up or surrender

themselves within four days after the notice

hereof, or otherwise we declare as follows.

That wherever the said persons shall reside,

be hid, or protected, we declare the owners,

masters, or inhabitants of the said places to be

confederates and traitors to the people and the

estates of them is also of all the aforesaid

persons to be confiscated. And this we, the

commons of Virginia, do declare, desiring a firm

union amongst ourselves that we may jointly and

with one accord defend ourselves against the

common enemy. . . . These are, therefore, in his

Majestys name, to command you forthwith to seize

the persons above mentioned as traitors to the

King and country and them to bring to Middle

Plantation and there to secure them until further

order, and, in case of opposition, if you want

any further assistance you are forthwith to

demand it in the name of the people in all the

counties of Virginia. Nathaniel Bacon General

by Consent of the people. William Sherwood