TAMUC Proposal Writing Workshop If you dont write grants, you wont get any - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 134

Title:

TAMUC Proposal Writing Workshop If you dont write grants, you wont get any

Description:

Social & Behavioral Sciences & Education Funding Agencies (NSF, NIH, DoED, HHS) ... Lucy Deckard, New faculty initiative, fellowships, physical science-related ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:253

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: TAMUC Proposal Writing Workshop If you dont write grants, you wont get any

1

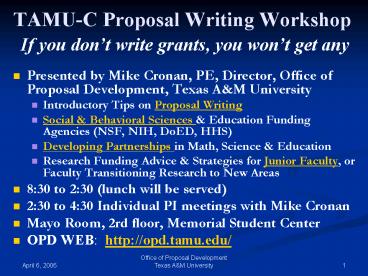

TAMU-C Proposal Writing Workshop If you dont

write grants, you wont get any

- Presented by Mike Cronan, PE, Director, Office of

Proposal Development, Texas AM University - Introductory Tips on Proposal Writing

- Social Behavioral Sciences Education Funding

Agencies (NSF, NIH, DoED, HHS) - Developing Partnerships in Math, Science

Education - Research Funding Advice Strategies for Junior

Faculty, or Faculty Transitioning Research to New

Areas - 830 to 230 (lunch will be served)

- 230 to 430 Individual PI meetings with Mike

Cronan - Mayo Room, 2rd floor, Memorial Student Center

- OPD WEB http//opd.tamu.edu/

2

Office of Proposal Development

- Unit of Vice President for Research Office

- Supports faculty in the development and writing

of research and educational proposals - center-level initiatives,

- multidisciplinary research teams,

- research affinity groups,

- junior faculty research,

- diversity in the research enterprise.

3

Office of Proposal Development, OPD-WEB

- OPD-WEB (http//opd.tamu.edu/) is an interactive

tool and faculty resource for the development and

writing of competitive research and educational

proposals to federal agencies and foundations - Funding opportunities (http//opd.tamu.edu/funding

-opportunities) - Junior faculty support (http//opd.tamu.edu/resou

rces-for-junior-faculty) - Proposal resources (http//opd.tamu.edu/proposal-r

esources) - Grant writing seminars (http//opd.tamu.edu/semina

r-materials) - Grant writing workbook (http//opd.tamu.edu/the-cr

aft-of-writing-workbook) - PI Observations

4

Members, Office of Proposal Development

- Jean Ann Bowman, ecological and environmental

sciences/ agriculture-related proposals and

centers, jbowman_at_tamu.edu - Libby Childress, Scheduling, resources, training

workshop management, project coordination,

libbyc_at_tamu.edu - Mike Cronan, center-level proposals, AM System

partnerships, new proposal and training

initiatives, mikecronan_at_tamu.edu - Lucy Deckard, New faculty initiative,

fellowships, physical science-related proposals,

equipment and instrumentation, interdisciplinary

materials group, OPD web management

l-deckard_at_tamu.edu - John Ivy (June 1), biomedical health related

initiatives, NIH - Phyllis McBride, craft of proposal writing

training, NIH and related agency initiatives in

the biomedical, social and behavioral sciences

editing and rewriting, p-mcbride_at_tamu.edu - Robyn Pearson, Education, social behavioral

sciences, and humanities-related proposals,

interdisciplinary research groups, editing and

rewriting, rlpearson_at_tamu.edu

5

Presenter Background

- Mike Cronan, P.E., has 15 years experience at

Texas AM University in planning, developing, and

writing successful center-level research and

educational proposals. - Author of gt 60 million in System-wide proposals

funded by NSF Texas AMP, Texas RSI, South Texas

RSI, Texas Collaborative for Excellence in

Teacher Preparation, CREST Environmental Research

Center, Information Technology in Science, CLT. - Named Regents Fellow (2000-04) by the Board of

Regents for his leadership role in developing and

writing NSF funded research and educational

partnerships across the AM System. - B.S., Civil Engineering (Structures), University

of Michigan, 1983 - M.F.A., English, University of California,

Irvine, 1972 - B.A., Political Science, Michigan State

University, 1968 - Registered Professional Engineer (Texas 063512,

inactive) - http//opd.tamu.edu/people

6

Open Forum, QA Format

- Audience is encouraged to ask questions

continuously - Audience questions will help direct, guide, and

focus the discussion on proposal topics.

7

Generic Competitive Strategies

- Understanding the mission, strategic plan,

investment priorities, culture, and review

criteria of a funding agency will enhance the

competitiveness of a proposal. - Knowledge about a funding agency helps the

applicant make good decisions throughout the

entire proposal development and writing process.

8

Analysis of the funding agency

- Know the audience (e.g., program officers,

reviewers) and the best way to address them. - Identify a fundable idea and characterized it

within the context of the agency research

investment priorities. - Communicate your passion, excitement, commitment,

and capacity to perform the proposed research to

review panels.

9

Develop Agency Specific Knowledge Base

- Electronic Funding Alert Services / Email Alerts

- http//opd.tamu.edu/funding-opportunities/electron

ic-funding-alert-services-email-alerts - Grants.gov

- http//www.grants.gov/

- http//www.grants.gov/search/subscribeAll.do

- MYNSF

- http//opd.tamu.edu/funding-opportunities/electron

ic-funding-alert-services-email-alerts - NIH National Institutes of Health Listserv

- http//grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/listserv.htm

- U.S. Dept. of Education, EDINFO

- http//listserv.ed.gov/cgi-bin/wa?A1ind05Ledinf

o

10

Writing a competitive proposal

- Preparing to write

- Developing hypothesis research plan

- Preliminary data background data

- Writing the proposal

11

Preparing to write a competitive proposal

- Develop a sound, testable hypothesis

- Ask other faculty to review proposal for

competitiveness of ideas and appropriateness to

agency - Understand the program guidelines (RFP)

- Relationship with program officers (e.g.,

NIH/NSF) - Understand funding agency culture, language,

mission, strategic plan, research investment

priorities (e.g. NIH Roadmap, NSF Strategic Plan) - Understand the agency review criteria, review

process, review panels (http//opd.tamu.edu/pro

posal-resources/understanding-the-proposal-review-

process-by-agency)

12

Developing the hypothesis research plan

- Review research currently funded by an agency

within your research domain (e.g., reports,

abstracts) - Communicate your research passion and capacity to

perform to reviewers - Know your audience (e.g., agency, program

officers, reviewers) - Explain how your research fits the agency

- Support claims of research uniqueness and

innovation - Build on your research expertise

- Do not present overly ambitious research plans

13

Preliminary data background data

- Present evidence of research readiness to show

the proposed work can be accomplished - Present evidence of institutional support for the

research (e.g., facilities, equipment

instrumentation) - Know what counts as preliminary and background

data and how much is sufficient - Map your research directions and interests to

funding agency research priorities (e.g. NIH

Roadmap)

14

Writing the proposal

- Tell a good story grounded in good science that

excites the reviewers and program officers - Ensuring the proposal is competitive for funding

- Proposal Form

- Use program guidelines as a proposal template

- Good writing, clear arguments, reviewer friendly

text (dont make reviewers work), organization,

figures, etc. - Proposal Content

15

If you dont write grants, you wont get any

- Important to have your proposal targeted. Look

for the intersection of - where research dollars are available

- your technical interests and

- where you can write a competitive proposal within

the time you have available. - Researchers have a lot of great ideas but if not

in scope of the agency it will not be funded - For proposals that have RFPs, or others that are

blue sky, unsolicited research, the key is to

have a good idea that you are enough of an

entrepreneur to sell someone else that it is a

good idea and worthy of funding.

16

If you dont write grants, you wont get any

- Get someone who writes well to read your proposal

for coherence and hook and to review the

writing, - Remember your reviewers are broader in scope than

your one proposal and if you get too technical

you get too many reviewers that dont understand - Some think if you submit your best idea it will

be stolen but if you submit your second best idea

it wont be funded .

17

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Relates to purposes goals of the applicant

agency. - Adheres to the content and format guidelines of

the applicant agency. - Establish your major points succinctly

repeatedly. - Directed toward the appropriate audience--i.e.,

those who review the proposal. - Write for technically diverse reviewers

intelligent readers, not experts - Avoid unnecessary complexity and technical

minutia

18

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Addresses the review criteria of the funding

agency. - Interesting to read compelling ideas conveys

excitement to reviewers. - Uses a clear, concise, coherent writing style,

free of jargon, superfluous information, and

undefined acronyms -- i.e., easy to read. - Organized in a logical manner that is easy to

follow use RFP as an organizational template. - Use of figures, graphs, charts, and other

visuals. - Proofread so it is free of grammatical errors,

misspellings, typos.

19

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Clear, concise, informative abstract that stands

alone and serves as roadmap to the narrative. - Clearly stated goals and objectives not buried in

a morass of dense narrative densely formatted. - Clearly documents the need to be met or problems

to be solved by the proposed project. - Indicates that the project's hypotheses rest on

sufficient evidence and are conceptually sound. - Clearly describes who will do the work (who), the

methods that will be employed (how), which

facilities or location will be used (where), and

a timetable of performance outcomes (when).

20

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Justifies the significance and/or contribution of

the project on current scientific knowledge. - Includes appropriate and sufficient citations to

prior work, ongoing studies, and related

literature. - Establishes the competence and scholarship PI

- Does not assume that reviewers "know what you

mean."

21

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Makes no unsupported assumptions.

- Discusses potential pitfalls alternative

approaches. - Plan for evaluating data or the success of

project. - Is of reasonable scope not overly ambitious.

- Work can be accomplished in the time allotted.

- Demonstrates that PIs and the organization are

qualified to perform the proposed project - Does not assume that the applicant agency "knows

all about you."

22

Elements of a Successful Proposal

- Includes vitae which demonstrate the credentials

required (e.g., do not use promotion and tenure

vitae replete with institutional committee

assignments for a research proposal.) - Documents facilities necessary for the success of

the project. - Includes necessary letters of support and other

supporting documentation. - Includes a bibliography of cited references.

23

Elements of a Successful Proposal Budget

- Has a budget which corresponds to the narrative

all major elements detailed in the budget are

described in the narrative and vice versa. - Has a budget sufficient to perform the tasks

described in the narrative. - Has a budget which corresponds to the applicant

agency's guidelines with respect to content and

detail, including a budget justification if

required. - The forgoing list was collected from various

sources, including Rebecca Claycamp, assistant

chair, Department of Chemistry, University of

Pittsburgh

24

Social Behavioral Sciences Education Funding

Agencies (NSF, NIH, HHS, DoED)

- Gain a better understanding of each agency

- Agency cultures

- Competitive strategies

- Comparisons among and between agencies

- Review processes

- Strategies for developing multidisciplinary

proposals

25

Types of Research Agencies Research

- Basic research agencies (NIH, NSF)

- Mission-focused agencies (DoED)

- Hypothesis-driven research

- Need- or applications driven research at

agencies. - http//opd.tamu.edu/the-craft-of-grant-writing-wor

kbook/manual/the-craft-of-grant-writing-workbook/a

nalyzing-funding-agencies

26

National Institutes of Health

- It is interesting to get the "other side of the

story" especially with respect to funding

priorities and how they can change very quickly

given specific research findings (not that the

funding is immediately available for new

projects, but more like decisions are made

quickly about how to re-prioritize). - Funding is definitely tight at NIH right now and

will be for the next few years. Applications have

to be exemplary and very much tied to the current

strategic plan of each institute and center. I

guess that's what you guys have been preaching

for some time....it just seems particularly

relevant now. - Susan E. Maier, Ph.D., Office of Scientific

Affairs, NIH/NIAAA (prior OPD)

27

NIH Reference Toolkit

- All About NIH Grants, Writing the R01

- http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/default.htm

- Annotated R01 Grant Application and Summary

Statement - http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/app/default.ht

m - How to Write a NIH Grant Application

- http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/write/write_pf

.htm - Advice for New Investigators Who is a New

Investigator? - http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/plan/plan_i1.h

tm - http//www.training.nih.gov/careers/careercenter/g

rants.html - Develop a Strong Hypothesis

- http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/plan/plan_c1.h

tm - Research Plan Section a. Specific Aims

- http//www.niaid.nih.gov/ncn/grants/write/write_j

1.htm - Proposal Writing The Business of Science (NIH)

- http//www.whitaker.org/sanders.html

- NIH Grant Writing Handbook, Univ. Pennsylvania

- http//www.med.upenn.edu/rpd/documents/gwm.pdf

28

Social Work Links HHS, NIH others

- HHS Funding (http//www.hhs.gov/grants/index.shtml

) - HHS Funding for Womens Health (http//www.4woman.

gov/fund/) - HHS Funding Opportunities, ACF (http//www.acf.hhs

.gov/programs/hsb/grant/fundingopportunities/fundo

pport.htm) - HHS Office of Community Services Funding

(http//www.acf.hhs.gov/grants/grants_ocs.html) - Research on Social Work Practice and Concepts in

Health (R01) (http//grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/p

a-files/PA-06-081.html) - Research on Social Work Practice and Concepts in

Health (R03) (http//grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/p

a-files/PA-06-082.html) - GWB School of Social Work, Washington Univ.

(http//gwbweb.wustl.edu/library/websites.html) - A Guide to Internet Resources in Social Work

(http//www.abacon.com/internetguides/social/webli

nks.html)

29

Social Work Links HHS others

- Social Work Internet Resources (http//www.hshsl.u

maryland.edu/resources/socialwork.html) - Institute for Advancement of Social Work Research

(http//www.charityadvantage.com/iaswr/TechnicalRe

sources.asp) - Ball State Social Funding (http//www.bsu.edu/oars

p/pubs/htmlnewsltr/dec2003/social.htm) - LSU Health Science Center Funding

(http//nursing.lsuhsc.edu/ResearchAndEvaluation/R

esearch/FundingOpportunities.html) - CNDC Funding (http//www.cndc2.org/funding_opportu

nities.htmrecent)

30

Selected Slides for NIH

31

(No Transcript)

32

(No Transcript)

33

(No Transcript)

34

(No Transcript)

35

(No Transcript)

36

NIH Don't Propose Too Much

- Sharpen the focus of your application. Novice

applicants often overshoot their mark, proposing

too much. - Make sure the scale of your hypothesis and aims

fits your request of time and resources. - Reviewers will quickly pick up on how well

matched these elements are. - Your hypothesis should be provable and aims

doable with the resources you are requesting.

37

NIH Develop a Solid Hypothesis

- Many top-notch NIH grant applications are driven

by strong hypotheses rather than advances in

technology (NSF, DoD counterpoint). - Think of your hypothesis as the foundation of

your application -- the conceptual underpinning

on which the entire structure rests. - Generally applications should ask questions that

prove or disprove a hypothesis rather than use a

method to search for a problem or simply collect

information.

38

NIH Develop a Solid Hypothesis

- Choose an important, testable, focused hypothesis

that increases understanding of biologic

processes, diseases, treatments, or preventions. - It should be based on previous research. State

your hypothesis in both the specific aims section

of the research plan and the abstract. - Avoid a fishing expedition. Reviewers see many

grants that did not have a hypothesis rather,

the investigator was obviously hoping that

something interesting would pop up in the course

of his or her investigation. That sort of

approach is not appealing to a study section.

39

NIH Applications Driven Research

- A new trend is pushing NIH toward more applied

research. - Especially in key areas, such as studies of

organisms used for bioterrorism, NIH is turning

more to applications seeking to discover basic

biology or develop or use a new technology. - If your application is not hypothesis-based,

state this in your cover letter and give the

reasons why the work is important.

40

Section a. Specific Aims

- Your specific aims are the objectives of your

research project, what you want to accomplish,

and your project milestones. - Write this section for audiences, primary

reviewers and other reviewers, since they'll all

read it. - Choose aims reviewers can easily assess.

- Your aims are the accomplishments by which the

success of your project is measured. - Recommended length of this section is one page.

- A common mistake new applicants make is being too

ambitious. You should probably limit your

proposal to three to four specific aims. - Design your specific aims and experiments so they

answer the question posed by the hypothesis.

Organize and define your aims so you can relate

them directly to your research methods.

41

NIH Investigator-initiated review criteria

- Significance

- Does the study address an important problem?

- Approach

- Are the design and methods appropriate to the

address the aims? - Innovation

- Does the project employ novel concepts,

approaches, methods? - Investigator

- Is the investigator appropriately trained to

carry out the study? - Environment

- Will the scientific environment contribute to the

probability of success?

42

Developing Partnerships in Mathematics, Science

Education

- There are three general categories of grants made

to universities by federal agencies that include

educational partnership components - research grants,

- integrated research and education grants, and

- education grants.

43

Key Partnership Infrastructures

- Developing educational partnerships or

partnerships to address agency specific

educational and outreach components to research

proposals, include - institutional commitment to the effort

- resources available on campus,

- effective models,

- evaluation and assessment capacities,

- defining long term objectives and outcomes.

44

Required Educational Partnerships

- Increasingly, principal investigators are

required by federal research agencies, most

notably the National Science Foundation, to

address educational or related activities in

research proposals. - At NSF, this requirement derives from two

agency-wide priorities 1) the agency strategy

for the integration of research and education and

2) the broader impacts review criterion

(http//opd.tamu.edu/proposal-resources/broaderimp

acts/main.html). - However, many researchers struggle with the

boarder impacts requirement, and often seek help

in developing this section of the proposal and

implementing and evaluating it if funded.

45

Educational Partnership Topics

- Topics will include

- Developing and writing educational components to

research grants, - Developing and writing any required evaluation

and assessment components - Linking to successful broader impacts models,

- Linking to other groups on campus that can

implement the required broader impacts or

educational components to research grants

46

Define Community of Interest

- Researchers

- Providers of educational components

- Providers of educational component models

- Providers of evaluation and assessment

- Writers of educational components of research

grants

47

Define Educational Components by Agency

- National Science Foundation

- Broader Impacts criterion

- Research-education integration core strategy

- Societal impacts

- National Institutions of Health

- Educational objectives mostly separate programs

- NASA Education and Public Outreach

- http//science.hq.nasa.gov/research/epo.htm

- http//ssibroker.colorado.edu/Broker/Eval_criteria

/Guide/Default.htm - Energy, NOAA, Others

48

NSF Broader Impacts

- The advance of discovery and understanding

- Improvement of the participation of

underrepresented groups - Enhancement of the education/research

infrastructure - Broad dissemination of results and

- Benefits of the activity to society at large.

- http//www.nsf.gov/pubs/2003/nsf032/bicexamples.pd

f

49

1. Tips on Developing Partnerships

- Fully committed PI with institutional support

- Beware good idea that lacks institutional

advocate - Analysis of the RFP

- Assemble proposal development team

- Partnerships/collaboratives are often more

competitive - Ensure team members "brings something to the

table"

50

2. Tips on Developing Partnerships

- Clearly define reasons for and nature of

partnership - State concise benefits of the partnership

- Review each team member's relevance to the RFP

- Develop major concepts specific to each RFP item

51

3. Tips on Developing Partnerships

- Develop strong arguments specific to each RFP

item or objective - Integrate specific objectives into overarching

vision or strategic plan - Integrate evaluation and assessment

(http//opd.tamu.edu/proposal-resources/online-pro

ject-evaluation-assessment-resources-for-principal

-investigators)

52

4. Tips on Developing Partnerships

- Initial teaming process and brainstorming will

not be linear - Distill concepts and arguments into linear

presentation - Converge drafts and interactions to final text

53

Research Funding Advice Strategies for Junior

Faculty Other Researchers

- How to be successful in winning funding early in

your research career - Special challenges and opportunities available to

new faculty as they work to establish their

research program and to compete for federal

research funding - NSF, NIH and related Young Faculty CAREER awards

54

1. How to be successful in winning funding

- Critical to gain as much informal insight into

funding situation as possible - Each agency has its own culture, its own track.

Your research should be what you love not just

what is popular - Make yourself known in the scientific community

and to reviewers. - Give talks at meetings, seminars know how to be

politically savvy and engaged with peer

community - Make your scientific enterprise work for you

- Publish

55

2. How to be successful in winning funding

- Experience working with large interdisciplinary

teams. Different agencies have a different view

of research. - Choose your opportunities carefully its easy

to see your own research interests in many

different solicitations, but you have to do your

homework and review the agency, the

solicitations, and look for related workshops and

primary documents that have led to the

solicitations. - Particularly at NSF, know your program manager.

Dont hesitate to call.

56

3. How to be successful in winning funding

- As junior faculty, if you have start-up funds,

you want to spend some of that to develop

preliminary data to develop your track record.

Use it as a foundation to move forward. - The role of mentors is critical. Some junior

faculty just need the support. Learning how to

write, learning about the agency. What does the

RFP really mean?

57

4. How to be successful in winning funding

- It is crucial to read the RFP very carefully.

Write to the RFP. You have to respond to every

item. - Proposals take a lot of effort. Dont lose

because of some overlooked requirement. - Get help from others who have read the RFP or who

have funding already. - Your summary or abstract is critical. That can be

what sells your proposal makes reviewers want

to keep reading. It should include all the

critical points of your proposal.

58

5. How to be successful in winning funding

- At NSF, it is very important to know the program

officers. They have power. They keep up with

trends in their field. They need to know your

name. Theyll work with you. - However, just because you know the PD doesnt

guarantee funding. There are checks and balances

at NSF. Theres still a peer review process. It

is a professional relationship, and its

objective. Just getting along with the program

officer wont turn bad science into good science.

59

6. How to be successful in winning funding

- Consider writing a white paper first,

particularly for unsolicited proposals to NSF,

defense agencies or others. - Call the program manager often there is money

set aside. Theyre looking for new ideas, but

wont just fund a cold proposal. Send the white

paper and ask if theyre interested or if they

know someone who might be. - This saves you time and gives you a reasonable

chance of getting funded. - A white paper is a broad-brushed outline what

you will gain and why it will be successful and

how youll do it, and rough costs.

60

7. How to be successful in winning funding

- It is informative to look at what has been funded

before, especially if youre having trouble

finding out what the RFP means. - Also, you can see workshop documents, etc. You

can prepare by going to workshops get to know

the research community and the program directors.

- If youre involved in the planning of future

directions, youre in a better position for

future funding. Might be difficult for a young

faculty, but certainly should do this as your

career develops.

61

8. How to be successful in winning funding

- A common mistake among young investigators is to

combine 3 projects into what should be only one.

Focus is the key term write a blue sky section

at the end, if you like, talking about what your

plans are for the future. - It doesnt matter how good your idea is if it is

not well presented, it wont get funded. The

opposite is also true no matter how well written

a proposal is, if the science isnt there, it

wont get funded. You have to have both form and

content. - If your proposal has grammatical errors or is

hard to follow, it can indicate sloppy research

to reviewers.

62

Twelve Steps To A Winning Research Proposal by

George A. Hazelrigg, NSF

- I have been an NSF program director for 18 years.

During this time, I have personally administered

the review of some 3,000 proposals and been

involved in the review of perhaps another 10,000.

Through this experience, I have come to see that

often there are real differences between winning

proposals and losing proposals. The differences

are clear. Largely, they are not subjective

differences or differences of quality to a large

extent, losing proposals are just plain missing

elements that are found in winning proposals.

63

1. Know yourself (Back)

- Know your area of expertise, what are your

strengths and what are your weaknesses. Play to

your strengths, not to your weaknesses. Do not

assume that, because you do not understand an

area, no one understands it or that there has

been no previous research conducted in the area. - If you want to get into a new area of research,

learn something about the area before you write a

proposal. Research previous work. Be a scholar.

64

2. Know program from which you seek support

- You are responsible for finding the appropriate

program for support of your research. Dont leave

this task up to someone else. If you are not

absolutely certain which program is appropriate,

call the program officer to find out. - Never submit a proposal to a program if you are

not certain that it is the correct program to

support your area of research. - Proposals submitted inappropriately to programs

may be returned without review, transferred to

other programs where they are likely to be

declined, or simply trashed in the program to

which you submit. In any case, you have wasted

your time writing a proposal that has no chance

of success from the get-go.

65

3. Read the program announcement

- Programs and special activities have specific

goals and specific requirements. If you dont

meet those goals and requirements, you have

thrown out your chance of success. - Read the announcement for what it says, not for

what you want it to say. - If your research does not fit easily within the

scope of the topic areas outlined, your chance of

success is nil.

66

4. Formulate an appropriate research objective

- A research proposal is a proposal to conduct

research, not to conduct development or design or

some other activity. Research is a methodical

process of building upon previous knowledge to

derive or discover new knowledge, that is,

something that isnt known before the research is

conducted. - In formulating a research objective, be sure that

it hasnt been proven impossible (for example,

My research objective is to find a geometric

construction to trisect an angle), that it is

doable within a reasonable budget and in a

reasonable time, that you can do it, and that it

is research, not development.

67

5. Develop a viable research plan

- A viable research plan is a plan to accomplish

your research objective that has a non-zero

probability of success. The focus of the plan

must be to accomplish the research objective. In

some cases, it is appropriate to validate your

results. In such cases, a valid validation plan

should be part of your research plan. - If there are potential difficulties lurking in

your plan, do not hide from them, but make them

clear and, if possible, suggest alternative

approaches to achieving your objective. - A good research plan lays out step-by-step the

approach to accomplishment of the research

objective. It does not gloss over difficult areas

with statements like, We will use computers to

accomplish this solution.

68

6. State research objective clearly in proposal

- A good research proposal includes a clear

statement of the research objective. Early in the

proposal is better than later in the proposal.

The first sentence of the proposal is a good

place. A good first sentence might be, The

research objective of this proposal is... Do not

use the word develop in the statement of your

research objective. It is, after all, supposed to

be a research objective, not a development

objective. - Many proposals include no statement of the

research objective whatsoever. The vast majority

of these are not funded. Remember that a research

proposal is not a research paper. - Do not spend the first 10 pages building up

suspense over what is the research objective.

69

7. Frame project around the work of others

- Remember that research builds on the extant

knowledge base, that is, upon the work of others.

Be sure to frame your project appropriately,

acknowledging the current limits of knowledge and

making clear your contribution to the extension

of these limits. - Be sure that you include references to the extant

work of others. Proposals that include references

only to the work of the principal investigator

stand a negligible probability of success. - Also frame your project in terms of its broader

impact to the field and to society. Describe the

benefit to society if your project is successful.

A good statement is, If successful, the benefits

of this research will be...

70

8. Grammar and spelling count

- Proposals are not graded on grammar. But if the

grammar is not perfect, the result is ambiguities

left to the reviewer to resolve. - Ambiguities make the proposal difficult to read

and often impossible to understand, and often

result in low ratings. Be sure your grammar is

perfect. - Also be sure every word is correctly spelled. If

the word you want to use is not in the spell

checker, consider carefully its use. Not in the

spell checker usually means that most people

wont understand it. With only very special

exceptions, it is not advisable to use words that

are not in the spell checker. Reviewers used to

say, Hes just an engineer. Dont mind the fact

that he cant spell. Now they say, Hes

proposing to do complex computer modeling, but he

doesnt know how to use the spell checker...

71

9. Format and brevity are important

- Do not feel that your proposal is rated based on

its weight. - Do not do your best to be as verbose as possible,

to cover every conceivable detail, to use the

smallest permissible fonts, and to get the

absolute most out of each sheet of paper. - Reviewers hate being challenged to read densely

prepared text or to read obtusely prepared

matter. Use 12 point fonts, use easily legible

fonts, use generous margins. Take pity on the

reviewers. Make your proposal a pleasant reading

experience that puts important concepts up front

and makes them clear. Use figures appropriately

to make and clarify points, but not as filler. - Remember, you are writing this proposal to the

reviewers, not to yourself. Remember that

exceeding page limits or other format criteria,

even marginally, can disqualify your proposal

from consideration.

72

10. Know the review process

- Know how your proposal will be reviewed before

you write it. Proposals that are reviewed by

panels must be written to a broader audience than

proposals that will be reviewed by mail. Mail

review can seek out reviewers with very specific

expertise in very narrow disciplines. This is not

possible in panels. Know approximately how many

proposals will be reviewed with yours and plan

not to overburden the reviewers with minutia.

Keep in mind that, the more proposals a panel

considers, the more difficult it will be for

panelists to remember specific details of your

proposal. - Remember, the main objective here is to write

your proposal to get it through the review

process successfully. It is not the objective of

your proposal to brag about yourself or your

research, nor is it the objective to seek to

publish your proposal. - Again, your proposal is a proposal, it is not a

research paper.

73

11. Proof read your proposal before it is sent

- Many proposals are sent out with idiotic

mistakes, omissions, and errors of all sorts. - NSF program managers have seen proposals come in

with research schedules pasted in from other

proposals unchanged, with dates referring to the

stone age and irrelevant research tasks.

Proposals have been submitted with the list of

references omitted and with the references not

referred to. Proposals have been submitted to the

wrong program. Proposals have been submitted with

misspellings in the title. - These proposals were not successful. Stupid

things like this kill a proposal. It is easy to

catch them with a simple, but careful, proof

reading. Dont spend six or eight weeks writing a

proposal just to kill it with stupid mistakes

that are easily prevented.

74

12. Submit your proposal on time

- Duh? Why work for two months on a proposal just

to have it disqualified for being late? Remember,

fairness dictates that proposal submission rules

must apply to everyone. It is not up to the

discretion of the program officer to grant you

dispensation on deadlines. That would be unfair

to everyone else, and it could invalidate the

entire competition. Equipment failures, power

outages, hurricanes and tornadoes, and even

internal problems at your institution are not

valid excuses. As adults, you are responsible for

getting your proposal in on time. If misfortune

befalls you, its tough luck. Dont take chances.

Get your proposal in two or three days before the

deadline.

75

Improve your prospects for success as an academic

researcher (by George A. Hazelrigg, NSF)

- There are two more things that you can do to

vastly improve your prospects for success as an

academic researcher. - First, you have to know yourself as well as you

can. Who are you? Where are you going? Where do

you want to go? I strongly urge people,

especially young faculty just starting their

careers, to write a strategic plan for their

life. Where are you today? Where do you want to

be in five years, ten years, twenty years? - Then create a roadmap of how to get from where

you are to where you want to be in the future.

The focus of this roadmap should be the things

over which you have control, and it should

acknowledge the things over which you have no

control. If you cant write such a plan, then

your goals for the future are not realistic. You

can revise the plan as often as you wish. But the

fact that the plan exists will influence your

proposal in a very positive way, as it will place

the research project you propose into the broad

context of your life plan.

76

Resources for Junior Faculty

- Resources for Junior Faculty

- http//opd.tamu.edu/resources-for-junior-faculty

- Funding for Junior Faculty

- http//opd.tamu.edu/funding-opportunities/funding-

opportunities-by-category/programs-for-junior-facu

lty.html

77

Early Career Programs for Faculty (Back)

- NSF CAREER

- DoD

- Young Investigator (ONR, ARL)

- Congressionally Mandated Directed Medical

Research Programs Young Investigator - NASA New Investigator Program in Earth-Sun

Systems - NIH

- Scientist Development Award for New Minority

Faculty - Career Development Awards (K-awards)

- Esp. Career Transition (K22) Award

- NIAMS Small Grants Program for New Investigators

78

Early Career Programs for Faculty

- Foundations

- Burroughs Wellcome Fund

- PhRMA Foundation

- Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Early Career

Fellowship in Economic Studies - Kellogg Forum Rising Stars, etc.

- Professional organization early career or

young investigator programs - American Philosophical Society Franklin

Research Grants - Listing of Programs

- http//www.spo.berkeley.edu/Fund/newfaculty.html

79

NSF CAREER Program

- Duration 5 years

- Funding level minimum 400K total (except min.

500K total for BIO directorate) - Eligibility

- Have a PhD

- Untenured, holding tenure-track Asst. Prof.

position or equivalent - Have not competed in CAREER more than two times

previously - Have not won a CAREER award

- Due July 19 21 depending on directorate

- Typical 10 20 success rate

- Solicitation http//www.nsf.gov/publications/pub_

summ.jsp?ods_keynsf05579

80

Key Points for CAREER

- Career Development Plan to build a firm

foundation for a lifetime of integrated

contributions to research and education - Where is your field going over the next 20 years?

- What will help you become established at national

level? - Establish that you have the experience and

resources to accomplish what you propose

81

Key Points (contd)

- Integrated Education Plan

- Along with Broader Impacts, often the

discriminator among many technically good

proposals - Looking for innovative approaches to integrating

education and research - Use strategic approach dont overburden yourself

with unreasonable education workload - Do what interests you, makes sense for your

project - Be sure to address diversity issues

82

Key Points (contd)

- Outreach and Broader Impacts

- Broaden participation of under-rep. groups

- Dissemination

- Societal benefits

- Improve infrastructure for research

- Discuss throughout proposal AND in separate

section in both Project Summary and Description - Connect to existing programs (ITS Center,

Research Experiences for Teachers, Research

Experiences for Undergraduates, Rural Systemic

Initiatives, etc. - more later)

83

Review Criteria

- Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts equally

weighted - Must show you have the skills to carry out the

project - Collaboration helpful, especially if moving into

new area need letter saying you are

collaborating (no co-PIs) - If moving into new area explain why this area

should be investigated - Data from your prior work good idea

- Publications in area greatly improves

competitiveness

84

Review Criteria

- Support from your department is critical

- Highlight benefits of your project to the

department (does it add important capabilities,

fit in with departments strategic plan, bring in

new infrastructure?) - Discuss any connections to NSF priority areas,

even if peripheral - State benefits of your research clearly

- Why is it important?

- How will it advance knowledge in field?

- Societal benefits

- Be sure to emphasize integration of education and

research

85

Strengths of Successful Proposals

- Novel or high-impact research focus

- Innovative research plan

- Education plan is well-developed, integrated with

research and includes some consideration of

evaluating its success - Education plan goes beyond routine course

development expected of all assistant professors - Quoted from J. Tornow presentation at QEM

Workshop http//qemnetwork.qem.org16080/tornow_pr

esentation/Joanne.htm

86

Weaknesses of Unsuccessful CAREER Proposals

- Research is either too ambitious or too narrowly

focused - Proposed methods do not address the stated

research goals - Educational component is either limited to

routine courses or is unrealistically

overambitious - Integration of research and education is weak or

uninspired - Quoted from J. Tornow presentation at QEM

Workshop - http//qemnetwork.qem.org16080/tornow_presentatio

n/Joanne.htm

87

Typical CAREER Review Process

- Program director identifies 3 to 6 reviewers with

expertise in technical area - Note PI can suggest reviewers

- Advantage if reviewers are familiar with PI or

PIs advisor - Proposal mailed to reviewers, who focus on

technical merit - Does research address an important question in

the field? - Is research innovative and exciting?

- Is it likely that the researcher will be

successful in reaching her/his goals - Are researchers goals and methods clear?

- May evaluate education, broader impacts but not

main focus

88

Typical Review Process

- After mail reviews, proposal reviewed by panel at

NSF - How well does proposed work integrate education

with research? - Is education plan innovative and does it make

sense for project? - What are broader impacts?

- How well does project promote diversity?

- Balance of topics of funded projects (i.e., wont

fund 10 projects in same area) - Process varies by directorate

- For example, Physics directorate does not have

mail reviews

89

Coming up with a Research Idea

- What do you want to do?

- Does it address important questions in your

field? - Is it novel and cutting-edge

- Not incremental improvement or refinement of

established research - Where is your field going in the next 20 years?

- Do you have the background and resources to

accomplish your goals? - If you are moving into a new but related area, be

sure you discuss collaborations with researchers

who will fill any gaps - Will it contribute to your career goals?

- Will it contribute to your departments goals?

- Important Talk to your department head and

research departmental goals!

90

Next Step Strategic Info Gathering

- Determine which NSF program to submit your

proposal to. - Extremely important! Submitting to wrong program

can doom good proposal. - Do this by e-mailing or calling program director.

- Have a paragraph summary of your proposed

research prepared. - Use NSF web site

- Search awarded CAREER projects in directorate

- Check program goals

- Talk to senior researchers in the area where are

they funded?

91

General Writing Advice

- Follow directions! (See solicitation, Grant

Proposal Guide) - Make it easy to read and understand

- Reviewer may be scanning your proposal on an

airplane - Use bullets, tables, graphs, illustrations as

much as possible this is what they will look at

first - Watch your font the Grant Proposal Guide gives

rules on minimum font size. Best to stay at 12

pt for readability

92

General Writing Advice (contd)

- Make the main points easy to find

- Put them at the beginning of the paragraph

- Use underline, bold, white space, etc.

- Specifically state all benefits of your project

- Even if its obvious to you, may not be obvious

to reviewer outside your area - Communicate your excitement!

93

Project Summary (1 page)

- Clearly address intellectual merit and broader

impacts separately (and label them) if you

dont , your proposal will be returned without

review! - This is a sales document and may be the only

thing the reviewer will read - Must pique the reviewers interest

- State up front the advantages of your project

(technical, societal, diversity, etc.) dont be

shy! - Summary should be clear and easy to read spend a

lot of time on this!

94

Project Description (15 pages)

- Description of proposed research project

- Description of proposed educational activities

- Description of how research and educational

activites are integrated - Results of Prior NSF support, if applicable (5

pgs max) - Last 5 years

- Report on only one program (most closely related)

95

Project Description

- Objectives and Significance

- Relation of research to current state of

knowledge - Outline of Plan of Work including evaluation of

education activities - Relation of plan to career goals and

responsibilities - Relation of plan to department goals

- Prior Research and Education Accomplishments

96

Project Description

- Objectives and Significance of Plan

- State your objectives clearly and at the

beginning include education goals - Describe briefly how your plan will advance

knowledge in the field, improve education,

provide societal benefits, etc. - Background relationship of research to current

state of knowledge in the field - Provide enough background to bring non-expert in

field up to speed and demonstrate your knowledge - Give plenty of references, particularly of

experts in field (who may be reviewing your

proposal) - Do not be dismissive of previous work

- Relationship of education activities to research

on effective teaching and learning in your field

97

Project Description (contd)

- Your Prior Work

- Describe what you have done to date in area

- Cite publications

- Present any data you have generated

- Establish your expertise in the area (or in

related area) - Use graphs, figures, etc. where possible

- Avoid too dense text

- Describe any directly related education

experience

98

Project Description

- Plan of Work

- Measurable goals and objectives (research,

education, diversity, outreach, etc.) - Methods and Procedures (include education

evaluation methods) - Be sure to discuss broader impact, diversity,

outreach, etc. - Include activity and milestone chart by year

(both research and education included in each

year)

99

Project Description

- Examples of Education Components

- Go more than would be expected as part of your

job - Develop a course related to your research

- Must be innovative (e.g., active learning

approach, technology assisted learning,

interdisciplinary outlook, connection with

industry, communication, ethics or sociology

component, etc. refer to NSF-funded Foundation

Coalition) - Involve undergraduates in research

- What is your goal?

- Encourage them to continue to grad school? Then

include mentoring, info on application process - Prepare them for industry? Then connect them

with industrial representatives, potential

internships - Innovative graduate student education

- Interdisciplinary focus, international component,

etc.

100

Treat Education as a Scholarly Enterprise

- Cite research and publications on best education

practices, suggested reforms - 1999 National Research Council report How People

Learn Brain, Mind, Experience, and School - NRC report Knowing What Students Know The

Science and Design of Educational Assessment. - NSF report SHAPING THE FUTURE New Expectations

for Undergraduate Education in Science,

Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology - The Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates

in the Research University, REINVENTING

UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION A Blueprint for

America's Research Universities - Discipline-specific pubs e.g., BIO 2010

Transforming Undergraduate Education for Future

Research Biologists (2003), Committee on

Undergraduate Biology Education to Prepare

Research Scientists for the 21st Century,

National Research Council of the National

Academies, The National Academies Press. - Pilot Study to Establish the Nature and Impact of

Effective Undergraduate Research Experiences on

Learning, Attitude, and Career Choice, Research

on Learning and Education (ROLE), David E.

Lopatto, Principal Investigator, Grinnell

101

Education Component

- Goals should be specific and measurable

- Evaluation should measure how well your approach

is working - E.g., percentage of undergrads mentored

continuing to grad school, improvement in test

scores, etc. - See NSF Handbook on Evaluation at

http//www.nsf.gov/publications/pub_summ.jsp?ods_k

eynsf02057 - Plans should include details to make them real

- E.g., Number of students served, need being

addressed with statistics - Check with your College for statistics on

enrollment, etc.

102

Broader Impacts and Outreach

- Address diversity issues!

- Examples (choose what interests you and make

sense for your project) - Work with K-12 teachers

- Research Experiences for Teachers (RET)

supplement - Connect with PEER Program

- Work with pre-service teachers

- Work with undergrads from other schools (e.g.,

minority serving) - Research Experiences for Undergraduates

supplement (is there an REU site in your

department?)

103

Broader Impacts More Examples

- Work with high school students on Science Fair

projects - Work with Community College teachers

- Collaborate with faculty from smaller and/or

minority serving institutions - Give them summer access to your facilities

- Connect to student chapters of minority

professional organizations (e.g., Society of

Women Engineers, Society of Mexican American

Engineers and Scientists) look for natural

connections

104

Career goals

- Relation of PIs Career goals to goals of

department/organization - Talk to your Department Head!

- Check planning documents for department and

reference - Reference Vision 2020 and how you will contribute

to these goals - http//www.tamu.edu/vision2020/

105

Departmental Endorsement (load under

Supplementary Docs)

- Letter from Dept Head

- Must be signed by Head with name, title, date

printed below signature - Proposed activities supported by and integrated

into goals of department and department will

support the development of the PI - Mentoring, Facilities, Summer salary (can list

components from your start-up package), etc. - Description of

- Relationship between project, PIs career goals

and responsibilities and department goals - Ways in which DH will ensure mentoring of PI

- Verification PI is eligible

106

Other Documents (contd)

- Supplementary Documents

- PI self-certification of eligibility (on

Fastlane) - Letters of commitment from collaborators

- No reference letters allowed

- 2-page bio

- see Grant Proposal Guide for format and follow it

(some directorates very picky!) - Current and Pending

- Lists currently funded project (from any source,

not just NSF) and any pending proposal for

external funding - See Grant Proposal Guide

- Facilities

107

Budget and Budget Justification

- No support of other Senior Personnel (faculty,

etc.) - Be sure to fund your educational activities also

- Budget Justification

- Another way to sell your ideas

- Make sure its easy to follow and supports the

stated work plan

108

Resubmissions

- Read and address reviews from last submission

- Reviewers will have access to your last

submission - Call your program officer for input

- Best soon after receiving reviews

- But if you have questions about some reviews,

call him/her now

109

ONR Young Investigator Program (Office of Naval

Research)

- 100,000 per year for three years

- FY 05 proposal was due 12 January 2006.

- FY07 announcement usually posted in September

- http//www.onr.navy.mil/sci_tech/archive_to_dvd/in

dustrial/363