POWER STRUCTURES, POLICY NETS - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 17

Title:

POWER STRUCTURES, POLICY NETS

Description:

... the Republican House's 2002 economic stimulus bill return $21 billion in ... Why did the bill give $10 million for bison-ranchers like Ted Turner, but no ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:54

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: POWER STRUCTURES, POLICY NETS

1

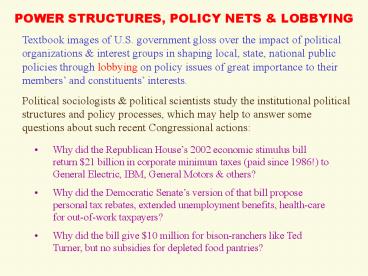

POWER STRUCTURES, POLICY NETS LOBBYING

Textbook images of U.S. government gloss over the

impact of political organizations interest

groups in shaping local, state, national public

policies through lobbying on policy issues of

great importance to their members and

constituents interests. Political sociologists

political scientists study the institutional

political structures and policy processes, which

may help to answer some questions about such

recent Congressional actions

- Why did the Republican Houses 2002 economic

stimulus bill return 21 billion in corporate

minimum taxes (paid since 1986!) to General

Electric, IBM, General Motors others? - Why did the Democratic Senates version of that

bill propose personal tax rebates, extended

unemployment benefits, health-care for

out-of-work taxpayers? - Why did the bill give 10 million for

bison-ranchers like Ted Turner, but no subsidies

for depleted food pantries?

2

POWER IS RELATIONAL

Power is inherently the property of a

relationship between two or more actors. Max

Webers two famous definitions explicitly

asserted that power (Macht) is not the resources

held by an actor, but occurs during situated

interactions involving actors with potentially

opposed interests and goals.

Power is the probability that one actor within

a social relationship will be in a position to

carry out his own will despite resistance,

regardless of the basis on which that probability

rests. (1947152) We understand by power the

chance of a man or a number of men to realize

their own will in a social action even against

the resistance of others who are participating in

the action. (1968962)

Some power is based on force (coercion). But, if

actors willingly assent or consent to obey

anothers commands, power becomes legitimate

authority (Herrschaft), which may be based on

actors traditional, charismatic, or

rational-legal beliefs in the rightness of their

relationship.

3

COLLECTIVE ACTION SYSTEMS

Collective action systems such as legislatures,

courts, regulatory agencies make public policy

decisions about numerous proposed laws and

regulations. Organized interest groups hold

varying pro/con preferences across multiple

policy decisions. Coalitions lobby public

officials to choose outcomes favorable to

coalitional interests. Decision makers may also

hold policy preferences, and may change their

votes on some events to gain support for

preferred decisions.

An actors structural interest is a revealed

preference, for a particular outcome, resulting

from identifiable social constraints or

influence, which may differ from an

unconstrained preference (Mizruchi Potts

2000231). Models of socially embedded

policymaking explore how network ties shape

collective decisions through information

exchanges, political resource, persuasion,

vote-trading (log-rolling), and other dynamic

processes.

4

POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS

Are organized interest groups substantially

different from SMOs?

Conventional view that social movements represent

outside challengers trying to get their views

heard inside the polity e.g., feminist,

anti-war, gay-lesbian, civil rights. SMOs may

resort to illegitimate tactics such as street

protests and violence. Interest groups are

legitimate insiders that pressure officials using

conventional political tactics, such as letters,

emails, and meetings.

Alternative views deny any meaningful

distinctions Both SMOs political orgs deploy

the full range of tactics in efforts to influence

outcomes of public policymaking

- Dual democratic functions of political orgs

- Aggregate and represent some citizens policy

preferences to elected appointed public

officials - Provide channel for officials to communicate

about benefits to their electoral constituencies

5

PROLIFERATING POLITICAL ORGS

Population ecology analysis of trade association

founding deaths rates reveals growth dynamics

during 20th century

Since 1960s, Washington and state capitals saw

rapidly rising numbers of business, professional,

labor, ethnic-racial, womens, environmental,

governmental, other political interest

orgs. Peak business assns NAM, BRT, Chamber of

Commerce reacted to increasing federal govt

intervention into the workplace economy.

6

LOBBYING TACTICS

Political orgs deploy a range of lobbying tactics

to influence elected appointed officials. In

descending frequency of use

- Testimony at legislative or agency hearings

- Direct contacts with legislators or other

officials - Informal contacts with legislators or other

officials - Presenting research results

- Coalitions with other groups planning strategy

with government officials - Mass media talking to journalists paid

advertising - Policy formation drafting legislation,

regulations shaping policy implementation

serving on advisory commissions agenda-setting - Constituent influence letter-writing or

telegram campaigns working with influential

citizens alerting legislators to district

effects - Litigation filing lawsuits or amici curiae

(friend of the court) briefs - Elections campaign contributions campaign

work candidate endorsements - Protests or demonstrations

- Other monitoring influencing appointments

doing personal favors for officials

7

LOBBYING STRATEGIES

Lobbying is NOT political bribery nor overt quid

pro quo dealing. Influence requires making the

most persuasive case Lobbyists give friendly

policy makers the information, substantive

analyses, politically accurate arguments about

why they should support the orgs preferred

solutions, instead of their opponents clearly

inferior indefensible proposals.

- Successful political orgs mobilize their

resources to achieve three strategic goals

(Browne 1998) - Winning attention outside game keeping the

publicity spotlight on the orgs issue agenda,

through the mass media in legislative and

regulatory arenas - Making contact inside game of schmoozing

building close network ties to officials,

lobbyists, and other brokers - Reinforcement lobbyists keep coming back,

showing their issues are still alive, reinforcing

both their access and previously discussed policy

matters

8

POLICY DOMAINS

Policy network analysts seek to explain the

formation of state-interest organization

networks, their persistence change over time,

and the consequences of network structures for

public policy-making outcomes.

Developers include British (Rhodes, Marsh),

German (Pappi, Schneider, Mayntz), American

(Laumann, Knoke) political scientists

sociologists

POLICY DOMAIN a set of interest group

organizations, legislative institutions, and

governmental executive agencies that engage in

setting agendas, formulating policies, gaining

access, advocating positions, organizing

collective influence actions, and selecting among

proposals to solve delimited substantive policy

problems, such as national defense, education,

agriculture, or welfare. (Laumann and Knoke.

1987. The Organizational State)

A policy network is described by its actors,

their linkages and its boundary. It includes a

relatively stable set of mainly public and

private corporate actors. The linkages between

the actors serve as channels for communication

and for the exchange of information, expertise,

trust and other policy resources. The boundary

of a given policy network is not in the first

place determined by formal institutions but

results from a process of mutual recognition

dependent on functional relevance and structural

embeddedness. (Kenis and Schneider 1991)

9

The ORGANIZATIONAL STATE

The Organizational State (1987) conceptualized

national policy domains power structures as

multiplex networks among formal organizations,

not elite persons. These connections enable

opposing coalitions to mobilize political

resources in collective fights for influence over

specific public policy decisions.

Power structure is revealed in patterns of

multiplex networks of information, resource,

reputational, and political support among

organizations with partially overlapping and

opposing policy interests. (See blockmodel

figures of U.S., German, Japanese labor policy

domains in Chapter 8 of Knoke et al.

1996.) Action set is a subset of policy domain

orgs that share common policy preferences, pool

political resources, and pressure governmental

decisionmakers to choose a policy outcome

favorable to their interests. After a policy

decision, the opposing action sets typically

break apart as new events give rise to other

constellations of interest orgs.

10

POLICY DOMAIN COMMUNICATION NETS

National policy domains orgs and institutions

engaged in efforts to create/change specific

policy proposals to solve substantive

problems EX health, energy, labor, agriculture,

defense Individuals are agents acting on behalf

of orgs interests (Marsh Smith 2000),

encountering principal-agent problems

Orgs central in a policy domain maintain numerous

communication ties, facilitating collaboration

policy information exchanges with potential

partners and with their opponents (for political

intelligence gathering)

Fig 9.6 (next slide) is a MDS plot showing the

core of the U.S. labor policy domain in 1988.

These interest orgs lie at short direct or

indirect communication distances, even though

many took the opposing sides on recurrent labor

policy fights (e.g., AFL-CIO vs National Assn of

Manufacturers, Business Round Table, Chamber of

Commerce)

11

LABOR DOMAIN COMMUNICATION CORE

1.5 0.0

-1.5

NLRB

HD

ACLU

NEA

SD

SR

UAW

ABC

AARP

CHAM

NAM

BRT

DOL

HR

AFL-CIO

TEAM

OSHA

ASCM

NGA

WHO

-1.5

0.0

1.5

SOURCE Knoke. 2001. Changing Organizations.

Westview.

12

LOBBYING TOGETHER or ALONE?

Interest org confronts transaction-cost and

free-riding questions in deciding when to join

others in an action set or to lobby alone?

- Its actions would have almost no impact on

obtaining the collective good (public policy) - It would maximize its gains by contributing

nothing yet enjoying whatever policy benefits the

other participants might succeed in producing

Mancur Olsons solution? Offer selective

incentives for orgs to join a coalition access

to contacts, insider information, enhanced orgl

reputation as a powerful policymaking player in

a policy domain

- Marie Hojnacki (1997) found that fewer than

one-third of 172 orgs worked alone in lobbying on

five policy proposals - Org with very narrow issue interests was more

likely to work by itself - If opponents were strongly organized allies

saw the interest org as crucial to their policy

success, then it was more likely to join coalition

13

LOBBYING COALITIONS

When its interests are at stake in a

Congressional bill or regulatory ruling, a

political org can lobby alone or in coalition

- Most political orgs work in coalitions a

division of labor - Coalitions are short-lived affairs for specific

narrow goals - EX impose or lift restrictions on Persian rug

imports - Partners in next coalition change with the

specific issues - Politics makes strange bedfellows EX Civil

liberties - Orgs that lobby together succeed more often than

soloists - Broad cleavages emerge within some policy

domains - EX Business vs Unions in labor policy domain

(next slide)

14

POLITICAL CLEAVAGES on EVENTS

Memberships in action sets for 3 U.S. labor

policy domain events revealed overlapping

patterns of organizational interests in

influencing these policy decisions. The labor

and business coalitions comprise a core set of

advocates (AFL vs. Chamber of Commerce) plus

event-specific interest organizations,

particularly nonlabor allies of unions.

SOURCE p. 354 in Knoke. 2001. Changing

Organizations.

15

WHO WINS POLICY FIGHTS?

- We know much less about the systematic influence

of political action on the outcomes of public

policy fights - No single political organization or enduring

coalition prevails on every issue event of

importance to it incrementalism prevails - What implications for Ruling Class, Elite,

Pluralist models? - Biggest PAC contributors campaign workers may

enjoy greater access, easier victories on

uncontested policy pork proposals - But why Big Tobaccos setbacks? Union failure to

block NAFTA? - Roll-call analyses of Congressional votes find

small lobbying effects relative to other factors - Lobbying impacts greatest in particular policy

events, depending on strength of oppositions

resources political arguments - Elected officials also pay attention to

unorganized voter opinions - Shockingly, some even hold ideological

principles hobby-horses!

16

DIALECTICAL INFLUENCES

Marsh Smiths dialectical model depicts policy

outcomes as feeding back to change actors and

network structures

Policy outcomes may affect networks by 1.

Changing network membership or the balance of

resources within it 2. Altering social contexts

to weaken particular interests in relation to a

given network 3. Causing agents, who learn by

experience, to pursue alternative policy

influence strategies actions

17

References

Aldrich, Howard E. and Udo Staber. 1988.

Organizing Business Interests Patterns of Trade

Association Foundings, Transformations, and

Death. Pp. 111-126 in Ecological Models of

Organizations, edited by Glenn Carroll. New York

Ballinger. Browne, William P. 1998. Groups,

Interests, and U.S. Public Policy. Washington

Georgetown University Press. Hojnacki, Marie.

1997. Interest Groups Decisions to Join

Alliances or Work Alone. American Journal of

Political Science 4161-87. Kenis, Patrick and

Volker Schneider. 1991. Policy Networks and

Policy Analysis Scrutinizing a New Analytical

Toolbox. Pp. 25-62 in Policy Networks Empirical

Evidence and Theoretical Considerations, edited

by Bernd Marin and Renate Mayntz.

Boulder/Frankfurt Campus/Westview Press. Knoke,

David. 2001. Changing Organizations Business

Networks in the New Political Economy. Boulder,

CO Westview Press. Knoke, David, Franz Urban

Pappi, Jeffrey Broadbent and Yutaka Tsujinaka.

1996. Comparing Policy Networks Labor Politics

in the U.S., Germany, and Japan. New York

Cambridge University Press. Laumann, Edward O.

and David Knoke. 1987. The Organizational State

Social Choice in National Policy Domains.

Madison, WI University of Wisconsin

Press. Marsh, David and M. Smith. 2000.

Understanding Policy Networks Towards a

Dialectical Approach. Political Studies

48(4)4-21. Mizruchi, Mark S. and Blyden B.

Potts. 2000. Social Networks and

Interorganizational Relations An Illustration

and Adaptation of a Micro-Level Model of

Political Decision Making. Research in the

Sociology of Organizations 17225-265. Weber,

Max. 1947. The Theory of Social and Economic

Organization. New York Free Press. Wber, Max.

1968. Economy and Society. New York Bedminster

Press.