Greek Masonry and Construction Techniques - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 24

Title:

Greek Masonry and Construction Techniques

Description:

The earliest example of substantial building in Greece was ... 5th ed. New York: Yale UP, Pelican history of art, 1996. Sadler, Simon. ' Lecture 3.' AHI025. ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:1145

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Greek Masonry and Construction Techniques

1

Greek Masonryand Construction Techniques

2

Masonry

Wall in Mycenae, built c. 1500 B.C.

- Cyclopean

- The earliest example of substantial building in

Greece was the Cyclopean masonry found in Mycenae

and nearby in other Bronze Age citadel cities. - It is unknown how the ancient Mycenaeans moved

such large stones, some of them, such as the

megalithic lintel stones over the Lions Gate,

weighing up to several tons. In fact, very little

is known about any of their construction

techniques. The skills were lost in the years

after the Bronze Age ended, around 1100 B.C. - What we know though, is that the stones were only

very slightly worked with tools, and were

probably found lying around the area rather then

quarried. Smaller chunks of stones would be

jammed between any cracks between the larger

ones. Because of the great mass and weight of the

larger stones, the walls proved to be very

durable and sturdy.

3

Polygonal

- When Greece came out of its Dark Age around 800

B.C., it had to reinvent the masonry skills it

saw in the ruins of Mycenae. - Unless rectangular blocks were necessary for

aesthetic reasons, masons tended to try and

imitate the Cyclopean style as best they could,

because it took less time and effort to work the

stones into proper shape. - They used smaller stones than seen in Cyclopean

masonry because they didnt have the technology

to move stones as large as those used in Mycenae. - In Polygonal masonry, masons cut blocks with

curved outlines and fit them together like a

puzzle, using the natural form of the rock - This masonry was very stable, and because they

interlocked so tightly, the wall didnt need any

extra support from metal clamps.

Delphi terrace wall, early sixth century

4

Horizontal

- About 500 B.C., it became high style to lay

blocks in more or less horizontal rows. This

sense of order was seen as more formal than the

irregularity of the polygonal masonry, and was

often used with temples and important civic

structures. - It was less stable than the interlocking

polygonal style though, and so the masons would

secure the blocks with horizontal clasps and

vertical metal dowels to prevent any lateral

shifting. - All of the metal was further fixed by a seal of

molten lead, all of this security important in

Greece, which was often hit by earthquakes. - With all of the metal used and the time it took

to finely shape the stone, this sort of masonry

was expensive, and saved for only the most

prestigious structures.

Priene street with supporting wall for the temple

of Athena Polias, fourth century

5

Ashlar / Isodomic

- This masonry was a fifth century development, and

basically a refinement of the horizontal masonry. - At the corners, the joints were often placed

perpendicular to one another in alternating

layers. - Generally this was used for smaller or highly

important surfaces as the regularity could seem

monotonous if carried on for too long. - Generally, for added interest, larger blocks were

used for the lower courses of the walls, and is

often seen in temples where the foundation is

above ground and where an intermediate size stone

softens the difference between the large

foundation slabs and the smaller ashlar stones.

The Erechtheion, Athens, c. 421-407 B.C.

6

Others

- Decorative Polygonal

- In the Hellenistic period, polygonal masonry came

back into style, but instead of selecting rocks

from the surface of the ground and just barely

working them, later masons deliberately carved

the stones into complex geometrical shapes. - This style was mainly reserved for decorative

masonry, real polygonal masonry was still used

for more utilitarian purposes.

Knidos terrace-wall 3rd- 2nd c.

7

Others

Others

- Decorative Polygonal

- In the Hellenistic period, polygonal masonry came

back into style, but instead of selecting rocks

from the surface of the ground and just barely

working them, later masons deliberately carved

the stones into complex geometrical shapes.

- Decorative Polygonal

- In the Hellenistic period, polygonal masonry came

back into style, but instead of selecting rocks

from the surface of the ground and just barely

working them, later masons deliberately carved

the stones into complex geometrical shapes.

Knidos terrace-wall 3rd- 2nd c.

The earlier polygonal from Delphi shows more

natural shapes, while the irregularities of the

later wall seem manufactured in comparison

8

Others

- Slanted Ashlar

- This style seems to be a sort of compromise

between polygonal and horizontal masonry. - The blocks are flat on the top and bottom and set

in relatively straight courses, the only

difference was that every so often, the sides

were cut on angles. - These angled edges retained some of the extra

stability polygonal masonry gave and so masons

felt safe to use this style for purposes such as

fortification despite the small block size, which

would usually lead to weaker walls. - Although most of the walls were still constructed

using Polygonal masonry, this provided a

cleaner-looking alternative for embellished

pieces of the walls.

Messene, city wall and tower, min 4th c.

9

Others

- Slanted Ashlar

- This style seems to be a sort of compromise

between polygonal and horizontal masonry. - The blocks are flat on the top and bottom and set

in relatively straight courses, the only

difference was that every so often, the sides

were cut on angles. - These angled edges retained some of the extra

stability polygonal masonry gave and so masons

felt safe to use this style for purposes such as

fortification despite the small block size, which

would usually lead to weaker walls. - Although most of the walls were still constructed

using Polygonal masonry, this provided a

cleaner-looking alternative for embellished

pieces of the walls.

Messene, city wall and tower, min 4th c.

10

Building Techniques

- Mystery of Mycenae

- When Greece regained an interest for monumental

building around 800 B.C., Mycenae was already in

ruins. - The Greeks knew that they still had the same

materials as their ancestors timber, mud bricks,

and stone, but they had forgotten the techniques

that the Mycenaeans had developed for their

massive structures. - The Greeks could only guess that the walls and

other structures must have been built by the

giant Cyclopes, hence the name Cyclopean masonry.

11

Dark Age of Greek History

- During the Dark Age of Greece, buildings had been

mainly made of sun-baked mud brick with timber

support frames and thatched roofs. - Buildings were not meant to be monumental, and

most sacred places were not temples but rather

natural formations such as caves. - Stone was used only for the base of the buildings

to keep water moister away from the mud walls,

but these unworked stones were generally just

those that were found on the surface of the

ground. - The buildings themselves were competently built,

but there was certainly little if any attempt of

elaboration, and everything was kept on a

relatively small scale as the proportions were

dependent of the size of the tree trunks they

could find.

12

Historical and Egyptian Inspiration

- Around 800 B.C., there was an increased interest

in the historical past, perpetuated by people

like Homer who told stories about the heroic past

of Greece. - Greeks wanted to emulate the style of their

ancient heroes, and were given the chance through

increased interactions with Egypt. - Around 660 B.C., the Greeks had given support to

Pharaoh Psamtik, who regained control of Egypt

from Assyrian control. His victory opened the

door for increased trade and communication, and

the Greeks founded a trading town named Naukratis

on the western Egyptian coastline around 620 B.C..

Homer

13

Megalithic Building

- Egypt built monumental works completely in stone,

and the Greeks eagerly studied their techniques

in order to develop their own style. - From the early seventh century onward, they would

have had new knowledge of how to dress stone as

well as how to physically put up such megalithic

buildings.

- One of the easiest comparisons between Greek and

Egyptian architecture is the Doric order. - The Greeks at first closely followed the Egyptian

models, although in their earlier temples it can

be seen that they still needed to develop their

refinement. - But although the Greeks did copy some of Egyptian

building techniques, their buildings in whole

were very different from their Egyptian

counterparts, keeping to traditional Greek forms.

Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Deir-el-Bahari,

Egypt, c. 1500 BC

14

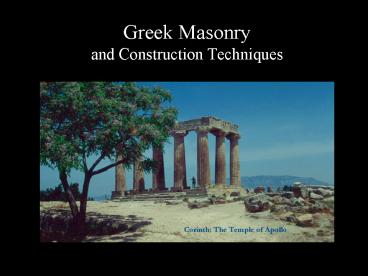

Megalithic Building

- Note that the Temple of Apollo, which is one of

the earliest examples of Greek megalithic

buildings, has monolithic columns. This would

later be refined by building the columns up in

drums rather than trying to carve the entire

pillar, which took larger pieces of stone and so

was both more expensive and more cumbersome.

Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Deir-el-Bahari,

Egypt, c. 1500 BC

The Temple of Apollo at Corinth, mid-6th century

B.C.

15

Steps to Construction The Architects Job

- In ancient Greece, there was no difference

between architect and engineer until the late

fourth century, and he was the most important

person on the project, sometimes even more so

than the patrons themselves. - The architect of the building project was

expected to control all details of workmanship,

inspect each course of stone before the next

could be laid down, approve the tightness of each

joint and the quality of the clamps, and

authorize payments to all the workmen and

contractors. - In fact, the only part of the building process

which he had no direct control over was the

quarrying process.

16

Steps to Construction Quarrying and Initial

Carving

- After the 6th century BC, the Greeks followed the

Egyptian method of quarrying. - Blocks were cut from the quarry on order from the

builder, and even column drums were sometimes

precut in their cylinder shape. - A channel would be cut around the block to the

depth of the height required and then it would be

detached from its base with wedges.

17

Steps to Construction Quarrying and Initial

Carving

- As Greek masons and architect refined their work,

temples (it was mostly temples that were built

with the best stonework) grew in size to a more

monumental scale. - As the temples grew, so did the size of the

required blocks if the style was to remain in the

same proportions.

- To ease the growing pressures on lifting and

transportation, stoneworkers would often hollow

out parts of the stone that werent essential to

the support of the building.

18

Steps to Construction Transporting the Stone

- Most blocks could be transported to the build

site in ox-drawn wagons, and this was the

standard practice. - The Greeks did at times use the Egyptian method

of having blocks moved on sledges and rollers,

but it wasnt practical for long distances, and

took too many men to execute properly.

- At times though, loads would become too heavy

for wagons, and new plans would have to be worked

out. Some worked while others not so much. - Lower left design was actually used by the

architect Cherisphron to move the architrave

blocks for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesos (c.

560 BC).

19

Steps to Construction Lifting and Leveling

- Once the blocks had arrived at the construction

site, the real work began. - The Greeks did employ the earthen ramp method of

the Egyptians, and even improved on the idea by

using sandbags instead of earth so that once the

stone block was in place, it could be lowered by

a controlled flow of sand as they loosened the

bags one by one. - A preferred method though, was the use of cranes,

much like the cranes we have today except made

mainly of wood and rope. - These cranes made it possible to have only a

small workforce of professional workmen on the

site, rather than the large mob it would take to

use other methods like the earth ramp, and so was

much more efficient and reasonable in a society

which didnt have the instant workforce which a

pharaoh would have.

20

Steps to Construction Lifting and Leveling II

- The cranes, however more efficient than ramps,

could only handle smaller sized blocks. - Multiple cranes could be used on one blocks, but

architects adapted to the machinery instead by

having the same structure made of smaller

individual units. - U-shaped notches or protruding bumps would be

carved into the stone pieces so that ropes would

have somewhere to attach to when the block was

lifted into place. - Once the blocks were set in place, as well as

during initial carving, masons would check that

the blocks were level using an A-shaped level.

This level had a plumb-line hanging from the

apex, which on a level plane would hang directly

between the two legs.

21

Steps to Construction Connecting and Finishing

- The column drums were connected by metal dowels

which were fixed with lead, and the regular

blocks of the walls were fixed by metal clamps

and lead as in general horizontal masonry

practices, with no mortar used. - To make sure everything looked regular and

aligned properly, the final carving was saved

until all the blocks were in place. - The stone was worked down with chisels until it

was finally smoothed by small stones and sand. If

it was marble, it could be further polished with

leather. - Completely finishing stone seemed to be reserved

for only the most important buildings, as it took

a lot of detailed work.

- The U-Shape holes on top, here for levers rather

than cranes because of the small stone size - The dove-tail clamp connecting the top of the two

stones - f) Preliminary finishing

22

Temples versus Secular

- Temples were unique to Greek architecture in that

their form never changed much. It was always a

post and lintel structure, mimicking the homes of

the early Greeks. - This is somewhat misleading, because the Greeks

did know about other construction methods such as

the arch, they just chose tradition instead of

new forms. - In fact, the arch and other more experimental

forms can be seen in secular structures. The arch

in particular, was saved for structures with

thicker walls, which would provide the proper

amount of buttressing for the outward thrust.

Parthenon, Athens, 447- 431 BC

23

Techniques Seen in Fortifications

- Because of their thick walls, fortifications (as

well as tombs) often had domes, because they

didnt need buttressing. - Seen here is also an example of cantilevering,

where the steps are supported only on one end of

the stone block which is embedded into the wall. - The Greeks though never built a dome larger than

the span of a small room. It would be the Romans

who would fully explore the use of domes as well

as other more experimental forms of stone

construction, aided dramatically by their

invention of concrete.

24

Bibliography

- Coulton, J. J. Greek Architects at Work. London

Elek Books Ltd., 1977. - Lawrence, A. W. Greek Architecture. 5th ed. New

York Yale UP, Pelican history of art, 1996. - Sadler, Simon. "Lecture 3." AHI025. ART 217. 14

Apr. 2008. - Tomlinson, Richard A. From Mycenae to

Constantinople The Evolution of the Ancient

City. New York Routledge, 1992.