FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 8

Title: FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care

1

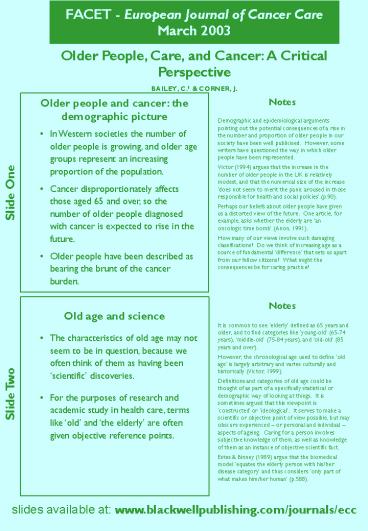

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective BAILEY, C.1 CORNER, J.

Slide One

Notes

- Older people and cancer the demographic picture

- In Western societies the number of older people

is growing, and older age groups represent an

increasing proportion of the population. - Cancer disproportionately affects those aged 65

and over, so the number of older people diagnosed

with cancer is expected to rise in the future. - Older people have been described as bearing the

brunt of the cancer burden.

Demographic and epidemiological arguments

pointing out the potential consequences of a rise

in the number and proportion of older people in

our society have been well publicised. However,

some writers have questioned the way in which

older people have been represented. Victor (1994)

argues that the increase in the number of older

people in the UK is relatively modest, and that

the numerical size of the increase does not seem

to merit the panic aroused in those responsible

for health and social policies (p.90). Perhaps

our beliefs about older people have given us a

distorted view of the future. One article, for

example, asks whether the elderly are an

oncologic time bomb (Anon, 1991). How many of

our views involve such damaging classifications?

Do we think of increasing age as a source of

fundamental difference that sets us apart from

our fellow citizens? What might the consequences

be for caring practice?

Slide Two

Notes

- Old age and science

- The characteristics of old age may not seem to be

in question, because we often think of them as

having been scientific discoveries. - For the purposes of research and academic study

in health care, terms like old and the

elderly are often given objective reference

points.

It is common to see elderly defined as 65 years

and older, and to find categories like

young-old (65-74 years), middle-old (75-84

years), and old-old (85 years and

over). However, the chronological age used to

define old age is largely arbitrary and varies

culturally and historically (Victor,

1999). Definitions and categories of old age

could be thought of as part of a specifically

statistical or demographic way of looking at

things. It is sometimes argued that this

viewpoint is constructed or ideological. It

serves to make a scientific or objective point of

view possible, but may obscure experienced or

personal and individual aspects of ageing.

Caring for a person involves subjective knowledge

of them, as well as knowledge of them as an

instance of objective scientific fact. Estes

Binney (1989) argue that the biomedical model

equates the elderly person with his/her disease

category and thus considers only part of what

makes him/her human (p.588).

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

2

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

Slide Three

Notes

- Age and functional status

- Older age is often presented in the health care

literature as part of a process of deterioration

and decline. - Older people are statistically more likely to

experience functional disability. - This may make it easier to justify the

association of an older person with his or her

disease category.

There is a risk of making primary sense of older

age as a period of increasing functional

impairment, physical limitation, and psychiatric

disorder. Older people may be thought of as

adding to the burden of health services that

are already stretched to their limits. Older

people, as a group, are sometimes interpreted as

a problem with severe consequences for the

economy and health and social care care

systems. Once defined as a problem, some people

argue, it is easier for social groups to be

thought of as the responsibility of experts

academics and professionals whose task it is to

develop policy and strategy. The focus shifts

from the individual to the expert. One view of

health care is that the power to define need and

establish expectations is largely in the hands of

professionals and academics whose knowledge gives

them expert status. Problematised groups are

vulnerable, and may be marginalised in terms of

their contribution to our understanding of

well-being.

Slide Four

Notes

- An example from research

- Koch Webbs (1996) study of older people in

hospital describes care that resembles a

routine or conveyor belt approach. - Individual requirements were not acknowledged.

- Patients disliked being segregated or labelled as

different on the basis of their age.

Baker (1983) argues that the routine geriatric

style of care is based on a notion of the older

person as a stigmatised individual

(pp.110-111), and that it puts orderliness above

individual need. Baker refers us to Goffman

(1968), who explains that someone who is

stigmatised is reduced in our minds from a

whole and usual person to a tainted or discounted

one (p.12). Koch Webb (1996) associate routine

care with a single set of norms that are

determined by the requirements of an

institutional schedule. Needs are defined not by

referring to the individual, but by referring to

a series of standard values and associated

nursing practices that include hygiene, pressure

area care, medication and food. They quote from

Ada, who has metastatic cancer I am sitting out

of bed but I dont want to be here. They just

sit everyone out of bed They are all resolved

to put everyone in their chairs. That is the

important thing (p.955).

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

3

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

Slide Five

Notes

- The biomedical construction of old age

- The biomedical view has been associated with

the idea of the person as a machine or container

for the mind. - As a machine, the body can be repaired, but can

also wear out over time. - This view tends to confirm the idea of ageing as

a time of deterioration and decay.

Interpretations of the body as a machine or

mechanism that is separate from the mind (or

self) may have important consequences for

caring practice, and for the care of older people

in particular. If we view our bodies as machine -

or object -like, it seems normal to allow

specialists in the repair of bodies a wide

degree of control over them. As a machine,

Koch Webb say, the body can be entered,

studied and tampered with in order to be

repaired (p.957). Attention to the objective

body means that the patient as subject fades

into the background, and the individual is left

with a diminished role in the process of setting

the agenda for care and well-being. The ageing

machine/body is subject to increasing amounts of

wear and tear, so that it becomes, in effect, a

failing mechanism. This, Koch Webb believe,

has contributed in health care to the negative

stereotyping of old age as a time of decay and

deterioration (p.958).

Slide Six

Notes

- Is old age just a way of thinking?

- Bytheway (1995) has argued that old age and

ageism are no more than ways of thinking. - He believes that we cannot rethink ageism

without questioning the presumption that old

age exists. - The elderly or the old could be thought of as

socially constructed categories that make it

legitimate to separate and manage people on the

basis of their chronological age.

According to Bytheway (1995), ageism is an

ideology, a shared system of ideas or beliefs

that justifies the interests of dominant groups

(GIddens, 1989). Bytheway explains that in health

care, doctors may, having taken account of

symptoms and clinical evidence, aim more for

amelioration than cure in their treatment of

older people (pp.127-8). If this practice is

based on clinical judgement and takes full

account of the benefits and risks of the

alternatives, it reflects a recognition of the

physical realities of age rather than the power

of ageism (p.128). If, however, treatments are

systematically barred to people over a certain

age because of a presumption that there will be

no benefit, or because younger people are

systematically given priority, or because limited

success could lead to a continuing burden, then

this is institutionalised ageism (p.128). To

take on ageism, we must, in effect, abolish the

idea that age is a legitimate basis for distance

or separation between individuals.

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

4

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

Slide Seven

Notes

- Images of older people

- Johnson Bytheway (1997) reviewed photographic

images of care work with older people from a

popular magazine. - The most common image was the caring about

photograph. - This image suggests that health care aspires to

care about as well as to care for older

people. - The images also suggest a view of older people as

passive, controlled, and dependent.

In the caring about photographs, Johnson

Bytheway found that both the younger carer and

the older cared about person were often women

(79 and 87 respectively). In a majority of the

photographs, the younger person is leaning

towards the older person (55) or taking up more

space (57). In some photographs, the younger

person is making a conscious effort to face the

older person on the same level. In others, the

younger person is more prominent, or the older

person appears to be on show, or an exhibit, to

be inspected by the younger person and the reader

(Johnson Bytheway, 1997, pp.136-7). This,

Johnson Bytheway believe, shows that the images

reflect the aspirations of health care to care

about as well as care for older people, as

well as a view of older people as passive,

controlled, and dependent (pp.137-8). Images

like these, they suggest, contrast sharply with

more realistic and challenging images that

ignore the association between age, care, and

dependence (p.141).

Slide Eight

Notes

- Non-persons and social death

- The very old and the sick have been identified as

categories of non-person. - A non-person is someone who is treated as if

they were not there. - Hospital patients can become non-persons before

their actual death, if other peoples behaviour

towards them reflects a recognition they they are

dying in a clinical sense. - Being treated as a non-person in this way has

been likened to a kind of social death.

It is Goffman (1959) who identifies the the old

and the sick as kinds of non-person, by which

he means people who are treated as if they were

not there. Mulkay Ernst (1991) say that the

sequence of physical decline that we call

dying is accompanied by a sequence of social

decline In many cases, although the patients

basic physiological requirements continue to be

met he or she ceases to exist as an active,

individual agent some time before biological

termination takes place (p.174). Mulkay Ernst

point out that older people are likely to find

themselves subject to a general physical

aversion which is akin to the revulsion caused

by dead bodies (p.181). They point to research

by Sudnow (1967) in which hospital staff are seen

to deal with all their elderly patients in a

special way which follows from the latters

proximity, as elderly persons, to biological

death ( p.181). In other words, elderly people

in hospital are already located in a social

death sequence.

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

5

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

Slide Nine

Notes

- Older people and acute illness

- Latimer (1997) describes the case of 91-year-old

Jessie, who has had a stroke, and argues that she

is classed by hospital staff as an old person

not an acutely ill person. - Her problems are interpreted as the natural

consequences of getting older. - She is therefore not the responsibility of

medical staff, and falls outside the legitimate

scope of health care.

Latimers ethnographic research was carried out

on an acute medical unit of a large British

hospital. Her account of Jessie is based on

conversations with a ward sister. She argues that

the category older people is absurd but

inescapable. We are all part of the process of

creating this distinction, because we all fear

increasing age. At the same time we are all

always already becoming older. The ward sister,

Latimer says, has refigured or redefined

Jessie by removing her from the category of

acutely ill person, and placing her in the

category of old person. Because ill health in

old age is seen as biologically inevitable, it is

part of the natural order of things. Jessie is

out of place in the medical ward because as an

old person, she is subject to progressive decline

until death, and is unlikely ever to fulfil

medical ambitions of an heroic recovery. The

primary association of ageing with physical

decline means that older people fit uneasily into

the domain of professional care.

Slide Ten

Notes

- Older people and cancer treatment

- Questions have been raised about certain aspects

of the treatment of older people with cancer. - Some research suggests that differences in

treatment received for cancer may be age-related. - Is there a rational explanation for the

differences in treatment received by older people

with cancer, or are the differences due to

ageism?

In 1991, Fentiman et al published a paper called

Cancer in the Elderly Why So Badly Treated? Even

ten years later, the question posed by this paper

sets us an important challenge to ensure that

older people are given the same opportunities as

their younger counterparts when they have

cancer. Some commentators believe that older

people with cancer can be subject to age bias

age-related differences in post-diagnostic

treatment suggest a deep social ageism

influencing who receives aggressive treatment

(Mor et al, 1985). Others believe there are good

reasons for age-related differences in treatment.

Guadagnoli et al (1997) conclude that in early

stage breast cancer, for example, the decline

with age in the frequency of adjuvant

chemotherapy is consistent with the diminished

efficacy of the treatment in older patients.

What is important is that we all take the

question of age-related differences in treatment

seriously.

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

6

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

Slide Eleven

Notes

- Chemotherapy

- Some research has shown that older people with

cancer do not receive adjuvant chemotherapy as

often as younger people. - Fear of increased toxicity may discourage doctors

from offering this kind of treatment to older

people. - Some studies suggest that older people, in

general, do not tolerate chemotherapy less well

than younger people.

Newcomb Carbone (1993) found that women aged

gt65 received radiotherapy and adjuvant

chemotherapy for breast cancer less often than

women aged lt65, and that chemotherapy for

colorectal cancer was less common in the older

age group. In their study, De Rijke et al (1996)

found that stage of disease was unknown in a

larger proportion of older patients, that older

patients were more likely not to be treated, and

that older patients were more likely to receive

single modality treatment. Popescu et al (1999),

who studied palliative and adjuvant chemotherapy

for colorectal cancer in patients aged gt70 years,

concluded that chemotherapy is well tolerated by

older patients, that the palliative benefits are

similar for fit older and younger patients, and

that adjuvant chemotherapy should be offered

using the same criteria that are applied to

younger patients. Schrag et al (2001) ask why

elderly patients do not receive potentially

curative adjuvant chemotherapy, and raise the

possibility of nonmedical barriers to care.

Slide Twelve

Notes

- Final thoughts

- The extent to which nonmedical barriers to care

affect older people with cancer should be

carefully considered. - We do not yet fully understand the influence of

age itself, social resources, cultural barriers,

professional attitudes, or patient preferences on

treatment decisions in older people with cancer. - Could better patient outcomes be achieved if we

could overcome some of these barriers?

There is an increased likelihood, with age, of

functional disability (Silliman et al, 1993), and

this might affect patients decisions not to

proceed with adjuvant treatment, for example.

The role of functional status and comorbidity in

decisions about adjuvant treatment is not fully

understood, however, and we need to know more

about exactly how important these factors are

when such treatment is either not offered or not

pursued. The question of whether patients do not

proceed with treatment because they judge

themselves ill-suited to do so, or whether they

are in effect prevented from doing so because of

some (potentially) remediable lack of necessary

support, is a particularly crucial one. We need

to ask ourselves whether, if comprehensive

support were to be more readily available, more

older people would choose to receive extended

treatments for their cancer. We might also ask

ourselves what, in these circumstances, the

effect on patient outcomes might be.

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

7

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

- References

- Anonymous (1991)The elderly an oncologic time

bomb? Annals of Oncology, 2(2) 82-83. - Baker, D. (1983) Care in the geriatric ward an

account of two styles of nursing. In Nursing

Research Ten Studies in Patient Care, edited by

J. Wilson-Barnett, John Wiley Sons, Chichester. - Bytheway, B. (1995) Ageism. Open University

Press, Buckingham. - Cancer Research Campaign (1992) Factsheet 5.1

Cancer in the European Community. Cancer

Research Campaign, London. - Estes, C.L. Binney, E.A. (1989) The

biomedicalisation of ageing dangers and

dilemmas. The Gerontologist, 29(5) 587-596. - Fentiman, I., Tirelli, U., Monfardini, S.,

Schneider, M., Fersten, J.F., Aapro, M. (1990)

Cancer in the elderly why so badly treated?

Lancet, 3351020-1022. - Giddens, A. (1989) Sociology. Polity Press,

Cambridge. - Goffman, E. (1959) The Presentation of Self in

Everyday Life. Doubleday, Garden City, New York. - Goffman, E (1968) Stigma Notes on the Management

of Spoiled Identity. Penguin Books,

Harmondsworth. - Guadagnoli, E., Shapiro, C., Gurwitz, J.H.,

Silliman, R.A., Weeks, J.C., Borbas, C.,

Soumerai, S.B. (1997) Age-related patterns of

care evidence against ageism in the treatment of

early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical

Oncology, 15(6)2338-2344. - Johnson, J. Bytheway, B. (1997) Illustrating

care images of care relationships with older

people. In Critical Approaches to Ageing and

Later Life, edited by A. Jamieson, S. Harper,

C. Victor, Open University Press, Buckingham. - Katz, S. (1996) Disciplining Old Age The

Formation of Gerontological Knowledge.

University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville. - Koch, T. Webb, C. (1996) The biomedical

construction of ageing implications for nursing

care of older people. Journal of Advanced

Nursing, 23(5)954-959. - Latimer, J. (1997) Figuring identities older

people, medicine, and time. In Critical

approaches to Ageing and Later Life, edited by A.

Jamieson, S. Harper, C. Victor, Open University

Press, Buckingham. - McCaffrey Boyle, D., Engelking, C., Blesch, K.S.,

Dodge, J., Sarna, L., Weinrich, S. (1992)

Oncology Nursing Society position paper on cancer

and ageing the mandate for oncology nursing.

Oncology Nursing Forum, 19(6), 913-933. - Mor, V, Masterson-Allen, S., Goldberg, R.J.,

Cummings, F.J., Glicksman, A.S., Fretwell, M.D.

(1985) Relationship between age at diagnosis and

treatments received by cancer patients. Journal

of the American Geriatric Society, 33(9)585-589. - Mulkay, M. Ernst, J. (1991) The changing

profile of social death. Archives of European

Sociology, XXXII172-196.

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc

8

FACET - European Journal of Cancer Care March 2003

Older People, Care, and Cancer A Critical

Perspective (continued)

- References (cont.)

- Popescu, R.A., Norman, A., Ross, P.J., Parikh, B.

Cunningham, D. (1999) Adjuvant or palliative

chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70

years and older. Journal of Clinical Oncology,

17(8)2412-2418. - Silliman, R.A., Balducci, L., Goodwin, J.S.,

Holms, F.F., Leventhal, E.A. (1993) Breast

cancer in older age what we know, dont know,

and do. Journal of the National Cancer

Institute, 85(3) 190-199. - Sudnow, D. ((1967) Passing On The Social

Organization of Dying. Prentice-Hall, Englewood

Cliffs, NJ. - Victor, C.R. (1994) Old Age in Modern Society A

Textbook of Social Gerontology. Chapman Hall,

London. - Victor C. (1999) What is old age? In Nursing

Older People, edited by S.J. Redfern F.M. Ross,

Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Footnotes 1Chris Bailey is Research Advisor for

the Wessex Primary Care Research Network, Primary

Medical Care, University of Southampton, and a

lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery,

also at the University of Southampton. Jessica

Corner is Professor of Cancer and Palliative

Care, School of Nursing and Midwifery, University

of Southampton. Correspondence address

C.D.Bailey_at_soton.ac.uk

slides available at www.blackwellpublishing.com/j

ournals/ecc