Walter Lippmann PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 8

Title: Walter Lippmann

1

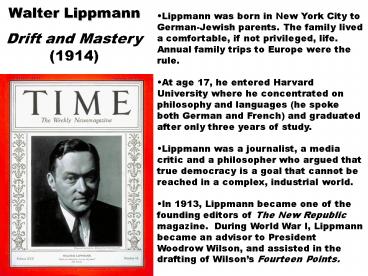

Walter Lippmann Drift and Mastery (1914)

- Lippmann was born in New York City to

German-Jewish parents. The family lived a

comfortable, if not privileged, life. Annual

family trips to Europe were the rule. - At age 17, he entered Harvard University where he

concentrated on philosophy and languages (he

spoke both German and French) and graduated after

only three years of study. - Lippmann was a journalist, a media critic and a

philosopher who argued that true democracy is a

goal that cannot be reached in a complex,

industrial world. - In 1913, Lippmann became one of the founding

editors of The New Republic magazine. During

World War I, Lippmann became an advisor to

President Woodrow Wilson, and assisted in the

drafting of Wilsons Fourteen Points.

2

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914)

- Early on, Lippmann was optimistic about American

democracy. He embraced the Jeffersonian ideal and

believed that the American people would become

intellectually engaged in political and world

issues and fulfill their democratic role as an

educated electorate. He later rejected this

view. - Lippmann coined the word stereotype and he

criticized journalists for stereotyping people.

He argued that seeing through stereotypes

subjected us to partial truths, and that when

analyzing a problem or event, people are more apt

to believe "the pictures in their heads" than

come to judgment by critical thinking.

3

During the 1920s, Walter Lippmann published two

of the most penetrating indictments of democracy

every written, Public Opinion and The Phantom

Public, valedictories to Progressive hopes for

the application of intelligence to social

problems via mass democracy. Instead of acting

out of careful consideration of the issues or

even individual or collective self-interest, the

American voter, Lippmann claimed, was

ill-informed, myopic, and prone to fits of

enthusiasm. The government, like advertising

copywriters and journalists, had perfected the

art of creating and manipulating public opiniona

process Lippmann called the manufacture of

consentwhile at the same time consumerism was

sapping Americans concern for public issues.

(Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom, p.

181.)

4

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914) 1.

There is a consensus that business methods need

to change. The leading thought of our world has

ceased to regard commercialism either as

permanent or desirable, and the only real

question among intelligent people is how business

methods are to be alerted, not whether they are

to be altered. 2. The chaos of too much

freedom and the weaknesses of democracy are our

real problem. The battle for us, in short, does

not lie against crusted prejudice, but against

the chaos of a new freedom. This chaos is our

real problem. So if the younger critics are to

meet the issues of their generation they must

give their attention, not so much to the evils of

authority, as to the weaknesses of democracy.

5

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914) 3.

Many are absorbed and overly worried about evil

conspiracies against society. The sense of

conspiracy and secret scheming which transpire is

almost uncanny. Big Business, and its ruthless

tentacles, have become the material for the

feverish fantasy of illiterate thousands thrown

out of kilter by the rack and strain of modern

life. It is possible to work yourself into a

state where the world seems a conspiracy and your

daily gong is beset with an alert and tingling

sense of labyrinthine evil. Everything askewall

the frictions of life are readily ascribed to a

deliberate evil intelligence, and men like Morgan

and Rockefeller take on attributes of

omnipotence, that ten minutes of cold sanity

would reduce to a barbarous myth.

6

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914) 4.

Although there is little legal basis for it, the

standards of the public life are being applied to

certain parts of the business world, thus making

businessmen think more about their

responsibilities, and their stewardship.

As muckraking developed, it began to apply the

standards of public life to certain parts of the

business world. The cultural basis of property

is radically altered, however much the law may

lag behind in recognizing the change. So if the

stockholders think they are the ultimate owners

of the Pennsylvania railroad, they are colossally

mistaken. Whatever the law may be, the people

have no such notion. And the men who are

connected with these essential properties cannot

escape the fact that they are expected to act

increasingly as public officials What puzzles

them beyond words is that anyone should presume

to meddle with their business. What they will

learn is that it is no longer altogether their

business. The law may not have realized this, but

the fact is being accomplished, and its a fact

grounded deeper than statutes. Big business men

who are at all intelligent recognize this. They

are talking more and more about their

responsibilities, their stewardship. It is

the swan-song of the old commercial profiteering

and a dim recognition that the motives in

business are undergoing a revolution.

7

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914) 5.

The crime is serious in proportion to the degree

of loyalty that we expect. American life is

saturated with the very relationship which in

politics we call corrupt. But in the politician

it is mercilessly condemned. In literal truth

the politician is attacked for displaying the

morality of his constituents. I suppose that

from the beginning of the republic people had

always expected their officials to work at a

level less self-seeking than that of ordinary

life. So that corruption in politics could never

be carried on with an entirely good conscious.

But at the opening of this century, democratic

people had begun to see much greater

possibilities in the government than ever before.

They looked to it as a protector from economic

tyranny and as the dispenser of the prime

institutions of democratic life. But when they

went to the government, what they found was a

petty and partisan, slavish and blind, clumsy and

rusty instrument for their expectations. when

mens vision of government enlarged, then the

cost of corruption and inefficiency rose for

they meant a blighting of the whole possibility

of the state. Corruption became a real

problem when reform through state action began to

take hold of mens thought.

8

Walter Lippmann, Drift and Mastery (1914) 6.

Americans need to deal with life deliberately. We

should organize our society, and actively

formulate it and educate it. We should substitute

purpose for tradition. America is preeminently

the country where there is practical substance in

Nietzsches advice that we should live not for

our fatherland but for our childrens land. To

do this men have to substitute purpose for

tradition and that is, I believe, the

profoundest change that has ever taken place in

human history. We can no longer treat life as

something that has trickled down to us. We have

to deal with it deliberately, devise its social

organization, alter its tools, formulate its

method, educate and control it. In endless ways

we put intention where custom has reigned. We

break up routines, make decisions, choose our

ends, select means.