The Conditional Nature of Administrative Responsiveness to Public Opinion PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 1

Title: The Conditional Nature of Administrative Responsiveness to Public Opinion

1

Table 1. The Federal Communication Commission

Responsiveness to Public Opinion

The Conditional Nature of Administrative

Responsiveness to Public Opinion

Julia Rabinovich

Northwestern University

Comparative Static

Abstract

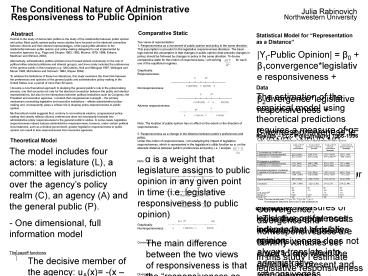

Statistical Model for Representation as a

Distance

Central to the study of democratic politics is

the study of the relationship between public

opinion and policy. Most public opinion-policy

nexus studies have focused on the electoral

connection between citizens and their elected

representatives, while paying little attention to

the relationship between public opinion and

policy-making delegated to and implemented by

executive agencies (e.g., Page and Shapiro 1983,

1992 Monroe 1979, 1998 Erikson, MacKuen and

Stimson 2003). Alternatively, administrative

politics scholars have focused almost exclusively

on the role of political elites (elected

politicians and interest groups), and have rarely

included the preferences of the general public in

their analyses e.g., McCubbins, Noll and Weingast

1987, Weingast and Moran 1983, McCubbins and

Schwartz 1984, Shipan 2004) . To address the

limitations of these two literatures, this study

examines the direct link between the preferences

and opinions of the general public and

administrative policy-making in the United States

over a period of more than 30 years. I develop a

new theoretical approach to studying the general

publics role in the policymaking process, one

that accounts not only for the electoral

connection between the public and elected

representatives, but also for the interactions

between political institutions such as Congress,

the President and executive agencies. I contend

that congressional oversight the primary

mechanism connecting legislative and executive

institutions affects administrative

policy-making and, consequently, plays a critical

role in shaping policy responsiveness to public

opinion. My theoretical model suggests that,

contrary to conventional wisdom, congressional

policy-making that closely reflects citizens

preferences does not necessarily translate into

administrative policy responsiveness to the

general publics wishes. In some cases,

legislative responsiveness indeed induces

administrative responsiveness however, under

certain political circumstances, such as a

divided government, greater legislative

responsiveness to public opinion can result in

less responsiveness from executive agencies.

.

Two views of representation 1. Responsiveness as

a movement of public opinion and policy in the

same direction. This assumption is prevalent in

the legislative responsiveness literature. The

basic logic behind this assumption is that

changes in public opinion (that precede changes

in policy) should be followed by changes in

policy in the same direction. To devise

comparative static for this notion of

responsiveness, I am solving for

each one of the equilibrium regimes.

Graphically Responsiveness Nonresponsivenes

s Adverse responsiveness Note The

location of public opinion has no effect on the

extent or the direction of responsiveness. 2.

Responsiveness as a change in the distance

between publics preferences and policy. Under

this notion of responsiveness, I am analyzing the

impact of legislative responsiveness, which is

represented in the legislatures utility function

as a, on the absolute distance between publics

preferences and policy, i.e. I analyze Note a

is a weight that legislature assigns to public

opinion in any given point in time (i.e.

legislative responsiveness to public

opinion) Graphically Nonresponsiveness Conve

rgence Divergence

Yt-Public Opinion ß0 ß1convergencelegislati

ve responsiveness ß2divergencelegislati

ve responsiveness ß3nonresponsivenessle

gislative responsiveness ßiXi,t et where Yt

is a measure of administrative policy output at

time t. Convergence, divergence and

nonresponsiveness are dummy variables set equal

to one when the condition is present and zero

otherwise. Xi,t is a vector of control

variables, including committee preferences,

agency preferences and appropriation data and et

is an error term.

Data

The estimation of the empirical model using

theoretical predictions requires a measure of a

(X(P,NP) NP)/P-NP. However, while X(P,NP) can be

estimated using legislative voting behavior (ADA

scores in this study), there are no available

measures of legislative preferences independent

of public opinion. In this study I estimate

legislative responsiveness as a difference

between the actual voting behavior of the

legislature and the one predicted by public

opinion. Legislative responsivenessADA

score-ADA score predicted by Policy Mood

Results FCC Policymaking 1966-1996

Theoretical Model

The model includes four actors a legislature

(L), a committee with jurisdiction over the

agencys policy realm (C), an agency (A) and the

general public (P). - One dimensional, full

information model The payoff functions The

decisive member of the agency uA(x) -(x

A)2 The decisive member of the oversight

committee uC(x) -(x C)2 The decisive member

of the legislature uL(x) -a (x P)2 (1-

a)(x NP)2 Notice that what sets this model

apart from other models is that I divide

legislatures utility function into two separate

components the utility derived from serving the

public and the utility from other sources such as

legislators own preferences, interest groups

pressure, etc. The Sequence of Actions Stage

1 The agency makes a policy proposal (x). Stage

2 In response to the agencys proposal, the

committee either introduces a bill (b) or

refrains from introducing a bill (gatekeeping).

If the committee decides not to propose a bill,

the game ends and the outcome is the originally

proposed policy (x). Stage 3 If the committee

decides to introduce a bill to the floor, the

legislature can either accept, reject or amend

the proposed legislation. If the legislature

rejects the legislation, the outcome is the

originally proposed policy (x). If the

legislature accepts the legislation, the outcome

is the committees proposal (c). If the

legislature decides to amend the legislation, it

will set it at its ideal policy (assuming open

rule) and the final outcome would be an amended

bill (b). Equilibrium strategies (SPE) A, if

A (min (X (P, NP), C(X (P,NP)), max (X (P, NP),

C(X (P,NP))) regime 1 X max (X (P, NP), C(X

(P,NP), if A max - regime 2 min (X (P,

NP), C(X (P,NP), if A min - regime 3 where X

(P, NP) argmaxx?RUL(x)aP (1-a)NP and C (X

(P,NP)) 2C X(P,NP)

Conclusions

- The theoretical results indicate that

legislative responsiveness does not always

translate into administrative responsiveness - especially when the executive and the

legislature are far apart and publics

preferences are very close to either one of the

institutions - The theory directs us to reconsider the

specification of the policy responsiveness to the

public opinion - On the one hand, we might underestimate

responsiveness if we do not account for the

possibility of movement of policy and public

opinion in the same direction - On the other hand, we might overestimate

responsiveness if we do not account for the

various conditions for responsiveness - A need for further empirical investigation

The main difference between the two views of

responsiveness is that the responsiveness as a

distance view picks up the possibility that

public opinion and policy move toward each other.

The situation that would have been classified as

adverse responsiveness by the responsiveness as

a movement in the same direction view