Gender Typicality in Children - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 1

Title:

Gender Typicality in Children

Description:

Adults perceive boys and girls to sound different from one another well in ... As with adults, boys and girls' speech differs more in some sounds and sound ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:158

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Gender Typicality in Children

1

Gender Typicality in Childrens Spoken

NarrativesAcoustic and Perceptual

AnalysesStudents Heather Bauer, Alysse Zittnan,

Adviser Benjamin MunsonDepartment of

Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences, College of

Liberal Arts

- Gender Differences in Adults Speech

- Spoken language is highly variable. Variability

affects all aspects of language sentence

structures, discourse strategies, word choice,

and pronunciation. - Adult men and women pronounce speech sounds

differently from one another. These differences

are evident even in short stretches of speech,

and allow a talkers sex to be ascertained at

greater-than-chance levels even when other

aspects of linguistic variation are controlled - The differences are not solely the consequence of

anatomic and physiologic differences between the

sexes. We know this because - 1. They are language- and culture-specific (Van

Bejooijen, 1995) - 2. There is only a weak correlation between

variation in pronunciation and variation in the

morphology of the speech-production mechanism - 3. They are not across the board (Munson et

al., 2006). They are more evident in some sound

classes than in others. Moreover, there are - Gender Differences in Childrens Speech

- Adults perceive boys and girls to sound different

from one another well in advance of the sex

differentiation in the speech-production

mechanism that occurs at puberty (Perry, Ohde,

Ashmead, 2001 inter alia). - Gender differences in childrens pronunciation

are not across the board. As with adults, boys

and girls speech differs more in some sounds and

sound classes than others. - Ergo, sex differences are to represent learned

behaviors that are the result of selective

attention to and emulation of specific models in

the ambient language. - In our laboratory, we have studied gender

typicality in childrens speech by comparing the

productions of 5-13 year old boys with GID (i.e.,

boys whose gender expression has been deemed not

to meet cultural expectations) to children whose

gender expression is deemed to meet cultural

expectations (henceforth Expected Gender

Development EGD). This provides us with an

opportunity to study gender in speech without the

confounding influence of biological sex.

- Results Acoustic Analyses

- When the average acoustic characteristics of

vowels were considered, the only difference to

approach statistical significance was one measure

of formant frequencies of vowels. There were no

differences for the consonants s or sh - Regression analyses predicting perceived gender

typicality from acoustic variables found that

adult listeners paid particular attention to the

way the vowel /æ/ was spoken. There was a weak

association between the acoustic characteristics

of s and sh. This is consistent with

previous work on adults, in which it has been

shown that adult attend to the characteristics of

these sounds when judging the gender typicality

of adults' voices. Together, 41 of variance in

the ratings was accounted for.

- Speech Samples

- The recorded spoken narratives used in this

experiment were elicited by asking each child to

tell a story about a picture (see title banner).

This was taken from a standardized test of

childrens narrative abilities. Narratives were

elicited as part of a larger data-collection

protocol that included measures of single-word

productions and sentence repetitions. - Data from 28 children was used. Each speaker was

categorized as either younger (average age 7

years) or older (average age 10 years) and as

either GID or EGD. The diagnoses of GID were

made by psychometrists with expertise in

childrens gender development. We used seven

speakers from each category for a total of 28

narratives, varying in length from about 30

seconds to 1 minute.

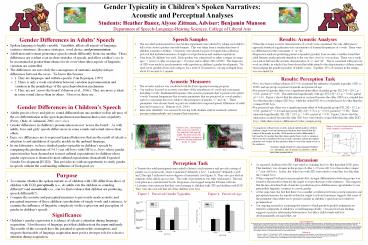

- Results Perception Task

- Two, two-factor within-subjects ANOVAs examined

the influence of gender typicality (GID vs. EGD)

and age group on perceived gender and perceived

age. - For perceived gender, there was a significant

main effect of gender group, F1,24 118.2, p lt

0.001, partial h2 0.83. This interacted

significantly with age, F1,24 4.6, p 0.042,

partial h2 0.16. Figure 1 shows that the

interaction occurred because the older GID boys

sounded less boy-like than the younger GID boys,

while the older EGD boys sounded more boy-like

than the younger EGD boys. - For perceived age, there was a significant main

effect of both gender group (F1,24 19.2, p lt

0.001, partial h2 0.44) and age group (F1,24

178.4, p lt 0.001, partial h2 0.88). These

interacted significantly, F1,24 24.0, p lt

0.001, partial h2 0.50. Figure 2 shows that

the interaction occurred because the older GID

boys were rated to sound older than the older EGD

boys, while there were no differences for the

younger group.

- Acoustic Measures

- The acoustic analysis was conducted with the

Praat signal-processing program. - Our analysis focused on acoustic correlates of

the articulation of vowels and consonants,

including vowels fundamental frequency (the

acoustic parameter that is perceived as pitch),

vowels formant frequencies (the acoustic

parameters that are perceived as vowel quality),

and two consonants known to relate to the

perception of gender, s and sh. These

parameters were chosen based on previous studies

that compared speech differences of adult men and

women (e.g., Munson et al., 2006). - Inter-rater reliability was assessed by having

both students analyze randomly selected passages

independently and compare their measures.

.

Figure 6. Perceived Gender based on Single

Words, Sentences, and Narratives

Figures 1 and 2. Spectrograms of the word sun

produced by a Boy with EGD (left) and

GID (right). The green circle is the s sound

and the red square is the first two formant

frequencies for the u sound.

- A comparison with previous acoustic and

perceptual analyses of these childrens single

word and sentence productions data showed that

the ratings of the gender typicality of the

narratives better differentiated between the two

groups than the ratings gender from words or

sentences - However, the correlation between acoustic

measures and the perceptual measures was weaker

for the narratives than it was for the single

words or the sentences. - Listeners might attended to suprasegmental

features (i.e., intonation, rate of speech) or

narrative content more than pronunciation

- Discussion

- As expected, children with GID were rated as

sounding less boy-like than their EGD peers.

This tendency was stronger in the groups of older

(10 year old) boys than in the younger (7 year

old) boys. In fact, the older boys with GID were

rated to sound less boy-like than the younger

boys. - When compared with previous perceptual data,

stronger differentiation between groups was found

for the narratives than for the single word

productions or the sentences. This suggests that

the less-structured task of narrative production

gives children more opportunities to use

permissible linguistic variation to convey gender - At the same time, the fact that there was a

smaller correlation between acoustic measures and

perceptual measures for narratives than for

single words and sentences suggests that some of

the parameters that adults use to perceive gender

in childrens speech are not related to

pronunciation. - Our ongoing research is examining the extent to

which gender-typicality judgments are related to

judgments of childrens overall language ability.

Our perceived age findings suggests a positive

relationship between how boy-like a child sounds

and how developmentally advanced they are.

- Perception Task

- Twenty-five adult participants were asked to

listen to each narrative and provide a rating of

gender on a 6-point scale, where 6 indicated

"definitely a boy", 1 indicated "definitely a

girl", and 2 through 5 indicated various degrees

of uncertainty (see Figure 3). They also

provided an estimate of the child's age in years.

The order of presentation was fully randomized.

The task took place in a sound-treated booth.

Responses were logged using the E-Prime software. - Listeners were unaware that they were listening

to children with GID and children with EGD. They

were also not told that all of the children were

boys.

- Purpose

- To examine whether the spoken narratives of

children with GID differ from those of children

with EGD perceptually (i.e., do adults rate the

children as sounding different?) and acoustically

(i.e., can we find evidence that children are

producing speech differently?) - Compare the acoustic and perceptual measures to

previously made acoustic and perceptual measures

of these childrens productions of single words

and sentences, to examine the influence of

linguistic complexity on the expression and

perception of gender in childrens speech - Significance

- Childrens gender expression is evidence of

selective attention during language acquisition.

Most theories of language posit that children

treat the input uniformly. The results of this

research have the potential to question this

assumption, and suggests that models of language

acquisition must posit a stronger role for

selective attention during acquisition.

Figure 3. Perceived Gender Typicality

Figure 4. Perceived Age

Acknowledgements The research on the acoustic and

perceptual characteristics of the speech of

children with Gender Identity Disorder was

completed in collaboration initiated by J.

Michael Bailey of the Northwestern University

Department of Psychology. The funding for the

data collection phase of this project was

provided by a grant to Janet Pierrehumbert

(Department of Linguistics, Northwestern

University) and J. Michael Bailey from the

Northwestern University Office of the Vice

President for Research. The data-collection

protocol was designed by Janet Pierrehumbert,

Benjamin Munson, and Karla K. McGregor

(Department of Speech-Language Pathology and

Audiology, University of Iowa). Data collection

was supervised by Ken Zucker (Clark Institute for

Mental Heath, Toronto, Ontario). The acoustic

analysis protocol was developed by Benjamin

Munson and Janet Pierrehumbert. The perceptual

analysis protocol was developed by Benjamin

Munson. All of the acoustic and perceptual

analyses described herein were conducted at the

University of Minnesota. The authors of this

poster take sole responsibility for the

interpretations that are presented herein, and

acknowledges that the different collaborators on

this project might interpret these same findings

differently. References Munson, B., Jefferson,

S.V. McDonald, E.C. (2006). The influence of

perceived sexual orientation on fricative

perception. Journal of the Acoustical Society of

America, 119, 2427-2437 Perry, T.L., Ohde, R.,

Ashmead, D. (2001). The acoustic bases for

gender identification from children's voices.

Journal of the Acoustical Society of America,

109, 2988-2998. Van Bezooijen, R. (1995).

Sociocultural aspects of pitch differences

between Japanese and Dutch women. Language and

Speech, 38, 253-265.