Unit 4 Using Abstract Data Types PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 240

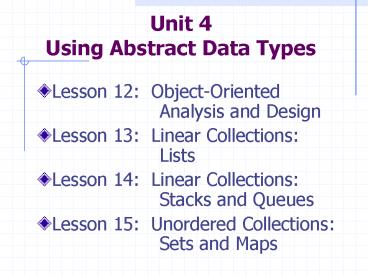

Title: Unit 4 Using Abstract Data Types

1

Unit 4Using Abstract Data Types

- Lesson 12 Object-Oriented Analysis and

Design - Lesson 13 Linear Collections Lists

- Lesson 14 Linear Collections Stacks and

Queues - Lesson 15 Unordered Collections Sets and

Maps

2

Lesson 12 Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

3

Lesson 12 Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

- Objectives

- Understand the general role of analysis and

design in the software development process. - Given a problem's description, pick out the

classes and their attributes. - Understand the role of a graphical notation such

as UML in object-oriented analysis and design.

4

Lesson 12 Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

- Objectives

- Interpret simple class diagrams and their basic

features. - Understand the difference between aggregation,

inheritance, and other relationships among

classes. - Given the description of an activity and its

collaboration diagram, write a narrative or

pseudocode for that activity.

5

Lesson 12 Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

- Vocabulary

- class diagram

- collaboration diagram

- has-a relationship

- is-a relationship

- knows-a relationship

- Unified Modeling Language (UML)

6

12.1 Introduction

- In the late 60s and in the 70s, the

ever-increasing size and complexity of software

systems lead to what was then a revolution in

software development techniques. - The first structured programming languages were

introduced, previously unstructured languages

were enhanced to make them structured, and

structured methodologies of analysis and design

were discovered and popularized.

7

12.1 Introduction

- In the mid-1990s companies began using

object-oriented languages and tools to develop

most of their new applications. - We have seen the introduction of object-oriented

operating systems and object-oriented database

systems. - Many of the software products and practices of

the preceding 40 years have been replaced by a

new generation of object-oriented ones.

8

12.1 Introduction

- Object-oriented methodologies are appealing

because they provide a single consistent model

and methodology for dealing with the three major

phases of software development - analysis,

- design,

- and implementation.

- The models used to illustrate small

object-oriented programs are exactly the same as

the one used to describe the decomposition of

large problems. - The ideas of abstraction, encapsulation, and

inheritance that are encountered when first

learning an object-oriented language are used

again when analyzing and designing large systems.

9

12.1 Introduction

- Analysis and design are at the heart of the

software development process, and numerous

techniques have been devised for assisting in the

task of doing object-oriented analysis and design

(OOAD). - These techniques have been grouped in various

combinations to form the methodologies that are

proclaimed in books and implemented in CASE

(Computer Aided Software Engineering) tools. - At the moment, the leading graphical notation

used in these methodologies is UML (Unified

Modeling Language).

10

12.2 Overview of Analysis and Design

- The goal of analysis is to model what a system

does. - The goal of design is to model how it might do

it. - During analysis fundamental classes,

interrelationships, and behavior are determined. - We do not draw a clear line of demarcation

between the two phases, however. - Together we treat them as a continuum of activity

that moves from the general to the specific,

finishing with a description of a system that can

be passed to programmers for coding.

11

12.2 Overview of Analysis and Design

- Determining the major classes needed in a system

is fairly straightforward. - The nouns in the description of a problem point

the way to an initial list of candidate classes

and their attributes. - Although classes are eventually organized into

hierarchies, it is best not to do this too soon,

but to wait until more insight is gained into the

workings of a system.

12

12.2 Overview of Analysis and Design

- Determining methods is more difficult.

- Verbs, to some extent, map into methods, but not

with the same reliability as nouns into classes

and attributes. - A better approach to discovering methods is to

examine the activities encompassed by a system. - Examining activities leads to an understanding of

the patterns of communications that exist between

the classes, and thus to knowledge of each

class's responsibilities and collaborators. - Role-playing and a blackboard are useful props

during this process, and the results are recorded

using the diagramming conventions of UML.

13

12.2 Overview of Analysis and Design

- Describing the function and signature of each

method completes analysis and design. - The process is iterative and implementing

prototypes can be very helpful. - At any time during the process there can be new

insights that lead to changes in work already

completed.

14

12.3 Request

- We are asked to implement an adventure game whose

broad outline is described as follows

Imagine a world of many places connected to each

other by paths (Figure 12-1 shows a corner of

such a world). Through this world a hero

wanders collecting treasures and weapons.

Dragons, giants, and other monsters guard the

items, so the hero must defeat these foes in

battle before picking up the items. A battle's

outcome depends on luck, the relative strength of

the contestants, and the power of their weapons.

Upon death an entity drops all its items, and

the hero can then pickup these items.

15

12.3 Request

As she moves from place to place, the hero

constructs a map of the portion of the world she

has seen so far. She also keeps a diary in

which she records the actions she performs during

the game (moving, picking things up, fighting

battles). As Figure 12-1 shows, the hero can

pass between the Great Hall and the Courtyard by

going through the great doors. From the

Courtyard, going south leads to the Stables, and

from the Stables going north returns to the

Courtyard. The hero has not finished exploring

the paths from the Great Hall. Stairs lead up

and down, and there is a secret door behind a

tapestry, but the destination of these paths is

currently unknown.

16

12.3 Request

17

12.4 Analysis

- Additional Facts Concerning the Game

- During interviews with the customer who requested

the software, additional details of the game are

learned. - Customer interviews are invaluable sources of

information and are an integral part of the

analysis process.

18

12.4 Analysis

- The object of the game is for the hero, under the

user's control, to collect 100 units of treasure

as quickly as possible and return to the entrance

without losing all of her nine lives. - Each treasure is worth some number of units.

- At the start of the game, the user does not know

how many treasures there are in the world. - There are many places, but no unreachable ones.

There may, however, be places from which there is

no return, such as the bottom of a deep well.

19

12.4 Analysis

- Each path connects two places, but some paths are

one way only, such as a wild raft ride down

dangerous rapids. - The hero passes instantly from place to place by

following the paths, and no game actions occur on

the paths. - Every place, path, entity, weapon, and treasure

has a name and description. - Until the hero follows a path, she does not know

where it leads, and once she does know, she adds

the destination to her map. Figure 12-1 shows the

hero's map after she has explored just a portion

of a giant's castle. In this illustration, the

entrance to the world is assumed to start at the

entrance to the castle.

20

12.4 Analysis

- The structure of an adventure world is stored in

a text file, and at the beginning of a game, the

user selects one of these files. At any time

during a game, the user can save the current

state of the game and exit. - At any given moment, an item (treasure or weapon)

is either carried by an entity or is lying around

in some place. Items are never located on paths.

21

12.4 Analysis

- The rules of battle are slightly convoluted.

- When the user enters a place guarded by one or

more monsters, she/he can avoid a battle simply

by leaving the place. - If the user decides to fight, she/he selects a

foe. - At that point, the numerical strength of the hero

is multiplied by one plus the numerical force of

all her weapons (strength (1 force of all

weapons)). - The resulting number is multiplied by a random

number between one and ten, representing luck, to

give what we call the battle number. - The same thing is done for the foe with whom she

is fighting. - The winner is whoever has the larger battle

number.

22

12.4 Analysis

- If the hero loses, she forfeits one of her nine

lives, and her strength is decremented by one. - If she loses her ninth life, the game is over.

- If there is a draw, there are no changes.

- If the monster loses, it drops all its items

(weapons and treasures) and dies, and the hero's

strength is incremented by one. - The user is able to view all relevant information

about the hero's and monster's state before

choosing to fight a battle.

23

12.4 Analysis

- The entries in the hero's diary vary depending on

the type of event recorded - Move (time, place, path, destination)

- Pickup (time, place, item)

- Battle (time, place, monster, hero's battle

number, monster's battle number) - The time indicates the elapsed time in seconds

since the beginning of the game. In addition, the

diary indicates the number of lives the hero has

remaining, her strength, and the total force of

all her weapons.

24

12.4 Analysis

- Graphical User Interface

- The overall requirement is to design an

interactive program that allows a user to enter

the game world and control the actions of the

hero. - The interface must display names and descriptions

of all things in the game, as well as the hero's

map and diary. - This interface is shown in Figure 12-2.

25

12.4 Analysis

26

12.4 Analysis

- OVERVIEW

- There are two menus

- The first (File) allows us to open and save the

game. - The second (Reports) displays the hero's map and

diary and redisplays the current place's

description. - The window's three lists and single text area

display relevant information about the state of

the game. - When the hero moves to a new location, the text

area displays a description of the place.

27

12.4 Analysis

- PATHS LIST

- A list of all the paths leading from the current

location. Clicking on a path's name causes the

path's description to display in the text area. - Here is the description of the secret door

- This door looks little used.

- Double clicking on a path causes the hero to move

along the path to its destination.

28

12.4 Analysis

- ENTITIES LIST

- This is a list of all the entities located in the

current place. - This includes the hero and her foes.

- Clicking on an entity displays its description in

the text area. - For instance, Hagarth is described as

- Hagarth A very giant of a giant.

- Strength 10

- Force of weapons 20

- Value of treasures 10

- Weapon Club Shaped from a tree trunk. Force 10.

- Treasure Belt Gold belt with diamond buckle.

Value 10. - Weapon Dagger As large as a small sword. Force

10.

29

12.4 Analysis

- Other interface items include

- Place Items list

- File/Open menu item

- File/Save menu item

- Reports/Map menu item

- Reports/Diary menu item

- Report/Current Location menu item

- Figure 12-3 displays a map and a diary report.

30

12.4 Analysis

31

12.4 Analysis

- Format of the Game's Text Files

- The structure of the file is the same for a new

game and for one saved during play. - Just as there are many ways to structure the

graphical user interface, so too there are many

ways to structure the text file. - We divide the file into labeled sections, and

each section contains multiple lines. - Figure 12-4 shows the structure

32

12.4 Analysis

33

12.4 Analysis

- Finding the Classes

- Our first step is to reread the extended

description of the problem and extract the nouns.

- Some of these nouns represent classes and others

represent attributes. - Ignore synonyms (different nouns that name the

same thing.) - Classes are of many different types -- people,

places, events, things, and abstractions, plus

interface and resource managers. - Table 12-1 shows our initial list of classes.

34

12.4 Analysis

35

12.4 Analysis

- We consider Map and Diary to be abstractions

because we are interested in their content rather

than their physical manifestation. - The entries in the diary record events.

- The GameFile class will handle all the details of

moving information in and out of the game file.

36

12.4 Analysis

- Representing Relationship between Classes

- INHERITANCE

- This is the relationship between a class and its

subclasses. - It is also called the is-a relationship, as in a

circle is-a shape. - AGGREGATION

- This is the relationship between a class and its

constituent parts, if they also happen to be

classes. - It is also called the has-a relationship, as in a

boat has-a rudder.

37

12.4 Analysis

- OTHER ASSOCIATION

- This category encompasses all other relationships

and is called the knows-a relationship. - In a problem description, these relationships

might be recognized by verbs such as carries,

eats, and rides and phrases such as "is next to." - Figure 12-5 shows how each of these relationships

is represented in UML using what are called class

diagrams.

38

12.4 Analysis

39

12.4 Analysis

- Relationship between the Classes in the Game

- In Figure 12-6, the generic word Entity

represents the hero and foes and Item represents

food and weapons

40

12.4 Analysis

41

12.4 Analysis

- To paraphrase, the diagram says that

The GameView displays the GameWorld. The

GameFile transfers the GameWorld to and from

disk. The GameWorld is an aggregate of one or

more (1..) places and paths. Each path

connects two places, and each place is connected

to at least one other. An entity is located in

a place, and an item is either located in a place

or carried by an entity. A place contains zero

or more (0..) entities and items, and an entity

carries zero or more items.

42

12.4 Analysis

- Many things in the game have a name and

description, which suggests introducing the

abstract superclass NamedThing. - Figure 12-7 summarizes these observations.

- The classes Map and Diary are not part of the

hierarchy, but are include in Figure 12-7 because

the hero carries them.

43

12.4 Analysis

44

12.4 Analysis

- Let us examine the relationship between the diary

and the events it records. - All the events have time and place in common,

which suggest an Event class. - In addition, each type of event (move, pickup,

and battle) has its own unique data requirements,

thus yielding the hierarchy shown in Figure 12-8

45

12.4 Analysis

46

12.4 Analysis

- Assigning Responsibilities

- In general terms, an object is responsible for

remembering its internal state (instance

variables) and for responding to messages sent to

it by other objects (methods). - As nouns help identify classes and their

attributes, so verbs in a problem's description

frequently indicate the methods that classes must

implement. - Following the advice we gave earlier about

distributing responsibilities among the classes

rather than allowing any single class to assume a

disproportionate role, we arrive at the

distribution illustrated in Table 12-3

47

12.4 Analysis

48

12.4 Analysis

49

12.5 Design

- Design is more exacting and technically difficult

than analysis. - It consists of devising the patterns of

communication needed to support the game. - In UML, this is done using collaboration

diagrams.

50

12.5 Design

- Activity Select a Path

- We begin with one of the simplest activities.

- The user clicks on a path.

- The interface responds by displaying a

description of the path. - The description does not include information

about where the path goes. - That can be discovered only by commanding the

hero to move along the path.

51

12.5 Design

- Activity Select a Path

- The implementation strategy is in three forms

- write a narrative that describes the sequences of

messages sent. - summarize the narrative in a collaboration

diagram. - write pseudocode for the methods revealed in the

previous two steps.

52

12.5 Design

- THE NARRATIVE

- Narratives are often the result of

experimentation. - When the best solution is not obvious, the

designer tries several different patterns of

communication and picks the one that is simplest.

53

12.5 Design

- The following is an example of part of our

narrative - When the user clicks on a path name, the Java

virtual machine calls the method listItemSelected

in the GameView. This method determines which

list the user clicked and calls a helper method. - The helper method, displaySelectedPath, asks the

GameWorld to get the path's name and description

by sending it the message getPathString(pathName).

54

12.5 Design

- THE COLLABORATION DIAGRAM

- The collaboration diagram in Figure 12-9 shows a

graphical representation of the narrative. - In the figure, rectangles represent objects of

the indicated classes. - The colons () are required.

- Arrows are labeled with the names of methods, and

numbers indicate the sequence in which the

methods are activated.

55

12.5 Design

56

12.5 Design

- THE PSEUDOCODE

- The narrative and the collaboration diagram

provide an excellent basis for writing pseudocode

that further clarifies our intentions. - As part of the pseudocode, we also list needed

instance variables.

57

12.5 Design

- Activity Pick Up an Item

- Picking up an item involves a fairly complex

pattern of communications. - Figure 12-10 shows a collaboration diagram for

the activity. - We assume that the user double clicks an item in

the Place Items list. - If there are any foes in the place or if the hero

has no lives left, then the action fails and a

message is displayed in the text area otherwise,

the selected item is moved from the place's list

to the hero's list and the interface is updated.

58

12.5 Design

59

12.5 Design

- In Figure 12-10, messages 1-6 cover removing the

item from the place and adding it to the hero. - Messages 7-9 update the Place Items list in the

user interface.

60

12.5 Design

- Activity Move

- The move activity is initiated when the user

double clicks a name in the Paths list. - If the hero has no lives left, she is not able to

move. - After the move is completed several aspects of

the interface are updated. - These updated items are detailed in Table 12-4.

61

12.5 Design

62

12.5 Design

- In the collaboration diagram (Figure 12-11) and

pseudocode, we update only the Paths list and

ignore the process of updating the Entities list,

the Place Items list, and the description in the

text area. - We also omit the messages and classes needed to

update the hero's diary.

63

12.5 Design

64

12.6 Implementation

- We now propose implementing the system in stages,

one activity at a time. - If there are flaws, we can correct them before

going too far in the wrong direction. - We write a method that creates a hard coded game

world. - The method, createHardCodedWorld, resides in the

GameWorld class and is called when the user

selects menu option File/Open. - With the hard coded game world as a basis, we

implement the activities of selecting a path and

moving.

65

Lesson 13 Linear Collections Lists

66

Lesson 13 Linear Collections Lists

- Objectives

- Distinguish fundamental categories of

collections, such as linear, hierarchical, graph,

and unordered. - Understand the basic features of lists and their

applications. - Use the list interface and the major list

implementation classes.

67

Lesson 13 Linear Collections Lists

- Objectives

- Recognize the difference between index-based

operations and content-based operations on lists. - Use an iterator to perform position-based

operations on a list. - Understand the difference between an iterator

and a list iterator. - Describe the restrictions on the use of list

operations and iterator operations.

68

Lesson 13 Linear Collections Lists

- Vocabulary

- abstract data type (ADT)

- abstraction

- backing store

- children

- collection

- content-based operation

- free list

- graph collection

- head

- hierarchical collection

- index-based operation

- iterator

- linear collection

- list iterator

- object heap

- parent

- position-based operation

- tail

- unordered collection

69

13.1 Overview of Collections

- A collection is a group of items that we want to

treat as a conceptual unit. - Arrays are the most common and fundamental type

of collection. - Other types of collections include

- Strings

- Stacks

- Lists

- Queues

- Binary search trees

- Heaps

- Graphs

- Maps

- Sets

- And bags

70

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Collections can be

- Homogeneous

- All items in the collection must be of the same

type - Heterogeneous

- The items can be of different types

- An important distinguishing characteristic of

collections is the manner in which they are

organized.

71

13.1 Overview of Collections

- There are four main categories of collections

- Linear collections

- Hierarchical collections

- Graph collections

- And unordered collections

72

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Linear Collections

- The items in a linear collection are, like people

in a line, ordered by position. - Everyday examples of linear collections are

grocery lists, stacks of dinner plates, and a

line of customers waiting at a bank.

73

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Hierarchical Collections

- Data items in hierarchical collections are

ordered in a structure reminiscent of an upside

down tree. - Each data item except the one at the top has just

one predecessor, its parent, but potentially many

successors, called its children.

74

13.1 Overview of Collections

- As shown in Figure 13-2, D3s predecessor

(parent) is D1, and its successors (children) are

D4, D5, and D6. - A companys organization tree and a books table

of contents are examples of hierarchical

collections.

75

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Graph Collections

- A graph collection, also called a graph, is a

collection in which each data item can have many

predecessors and many successors. - As shown in Figure 13-3, all elements connected

to D3 are considered to be both its predecessors

and successors. - Examples of graphs are maps

- of airline routes between

- cities and electrical wiring

- diagrams for buildings.

76

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Unordered Collections

- Items in an unordered collection are not in any

particular order, and one cannot meaningfully

speak of an items predecessor or successor. - Figure 13-4 shows such

- a structure.

- A bag of marbles is an

- example of an

- unordered collection.

77

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Operations on Collections

- Collections are typically dynamic rather than

static, meaning they can grow or shrink with the

needs of a problem. - Their contents change throughout the course of a

program. - Manipulations that can be performed on a

collection vary with the type of collection being

used. - Table 13-1 shows the categories of operations on

collections.

78

13.1 Overview of Collections

79

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Abstract Data Types

- Users of collections need to know how to declare

and use each type of collection. - From their perspective, a collection is seen as a

means for storing and accessing data in some

predetermined manner, without concern for the

details of the collections implementation. - From the users perspective a collection is an

abstraction, and for this reason, in computer

science collections are called abstract data

types (ADTs).

80

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Abstraction is used as a technique for ignoring

or hiding details that are, for the moment,

inessential. - We often build up a software system layer by

layer, each layer being treated as an abstraction

by the layers above that utilize it. - Without abstraction, we would need to consider

all aspects of a software system simultaneously,

an impossible task. - The details must be considered eventually, but in

a small and manageable context. - In Java, methods are the smallest unit of

abstraction, classes and their interfaces are the

next in size, and packages, are the largest.

81

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Multiple Implementations

- The rationale for implementing different types of

collections tend to be based on four underlying

approaches to organizing and accessing memory - Arrays

- Linear linked structures

- Other linked structures

- Hashing into an array

82

13.1 Overview of Collections

- When there is more than one way to implement a

collection, programmers define a variable of an

interface type and assign to it an object that

uses the desired implementation. - For example, java.util includes three classes

that implement the List interface. - Theses classes are LinkedList, ArrayList, and

Vector. - In the following code snippet, the programmer has

chosen the LinkedList implementation

List lst new LinkedList()

83

13.1 Overview of Collections

- Collections and Casting

- With the exception of arrays, strings, string

buffers, and bit sets, Java collections can

contain any kind of object and nothing but

objects. - These constraints have several consequences

- Primitive types, such as int must be placed in a

wrapper before being added to a collection. - It is impossible to declare a collection that is

restricted to just one type of object. - Items coming out of a collection are, from the

compilers perspective, instances of Object, and

they cannot be sent type-specific messages until

they have been cast.

84

13.2 Lists

- Overview

- A list supports manipulation of items at any

point within a linear collection. Some common

examples of lists include - A recipe, which is a list of instruction.

- A String, which is a list of characters.

- A document, which is a list of words.

- A file, which is a list of data blocks on a disk.

85

13.2 Lists

- Array implementations of lists use physical

position to represent logical order, but linked

implementations do not. - The first item in a list is at its head, whereas

the last item in a list is at its tail. - In a list, items retain position relative to each

other over time, and additions and deletions

affect predecessor/successor relationships only

at the point of modification. - Figure 13-5 shows how a list changes in response

to a succession of operations. - The operations are described in Table 13-2.

86

13.2 Lists

87

13.2 Lists

88

13.2 Lists

- Categories of List Operations

- There are several broad categories of operations

- Index-based operations

- Content-based operations

- And position-based operations.

89

13.2 Lists

- Index-based operations manipulate items at

designated positions within a list. - The head is at index 0

- The tail is at index n-1

- Table 13-3 shows some fundamental index-based

operations.

90

13.2 Lists

- Content-based operations are based not on an

index but on the content of a list. - Most of these operations search for an object

equal to a given object before taking further

action. - Table 13-4 outlines some basic content-based

operations.

91

13.2 Lists

- Position-based operations are performed relative

to a currently established position within a

list, and in java.util, they are provided via an

iterator. - An iterator is an object that allows a client to

navigate through a list and perform various

operations at the current position.

92

13.2 Lists

- The List Interface

- Table 13-5 lists the methods in the interface

java.util.List. - The classes ArrayList and LinkedList both

implement this interface.

93

13.2 Lists

94

13.2 Lists

95

13.2 Lists

96

13.2 Lists

97

13.2 Lists

- To make certain that there are no ambiguities in

the meaning of the operations shown in Table

13-5, we now present an example that shows a

sequence of these operations in action. - This sequence is listed in Table 13-6.

98

13.2 Lists

99

13.2 Lists

100

13.2 Lists

- Applications of Lists

- Heap Storage Management

- The object heap can be managed using a inked

list. - Heap management schemes can have a significant

impact on an applications overall performance,

especially if the application creates and

abandons many objects during the course of its

execution.

101

13.2 Lists

- In our scheme, contiguous blocks of free space on

the heap are linked together in a free list. - When an application instantiates a new object,

the JVM searches the free list for the first

block large enough to hold the object and returns

any excess space to the free list. - When the object is no longer needed, the garbage

collector returns the objects space to the free

list.

102

13.2 Lists

- To counteract fragmentation, the garbage

collector periodically reorganizes the free list

by recognizing physically adjacent blocks. - To reduce search time, multiple free lists can be

used. - If an object reference requires 4 bytes, then

- list 1 could consist of blocks of size 4,

- list 2, blocks of size 8,

- list 3, blocks of size 16,

- list 4, blocks of size 32,

- and so on.

103

13.2 Lists

- In this scheme, space is always allocated in

units of 4 bytes, and space for a new object is

taken from the head of the first nonempty list

containing blocks of sufficient size. - Allocating space for a new object now takes O(1)

time unless the object requires more space than

is available in the first block of the last list. - At that point, the last list must be searched,

giving the operation a maximum running time of

O(n), where n is the size of the last list.

104

13.2 Lists

- Organization of Files on a Disk

- A computers file system has three major

components - A directory of files,

- The files themselves,

- And free space.

105

13.2 Lists

- Figure 13-6 shows the standard arrangement of a

disks physical format. - The disks surface is divided into concentric

tracks, and each track is further subdivided into

sectors. - The numbers of these vary depending on the disks

capacity and physical size however all tracks

contain the same number of sectors and all

sectors contain the same number of bytes.

106

13.2 Lists

107

13.2 Lists

- Sectors that are not in use are linked together

in a free list. - When new files are created, they are allocated

space from this list, and when old files are

deleted, their space is returned to the list. - Because all sectors are the same size and because

space is allocated in sectors, a file system does

not experience the same fragmentation problem

encountered in Javas object heap.

108

13.3 Iterators

- An iterator supports position-based operations on

a list. - An iterator uses the underlying list as a backing

collection, and the iterators current position

is always in one of three places - Just before the first item

- Between two adjacent items

- Just after the last item

109

13. Iterators

- Initially when an iterator is first instantiated,

the position is immediately before the first

item. - From this position the user can either navigate

to another position or modify the list in some

way. - For lists, java.util provides two types of

iterators - a simple iterator

- and a list iterator.

110

13.3 Iterators

- The Simple Iterator

- In Java, a simple iterator is an object that

responds to messages specified in the interface

java.util.Iterator, as summarized in Table 13-9

111

13.3 Iterators

- You create an iterator object by sending the

message iterator to a list, as shown in the

following code segment - The list serves as a backing store for the

iterator. - A backing store is a storage area, usually a

collection, where data elements are maintained. - The relationship between these two objects is

depicted in Figure 13-8. - The methods hasNext and next are for navigating,

whereas the method remove mutates the underlying

list.

Iterator iter someList.iterator()

112

13.3 Iterators

113

13.3 Iterators

- The next code segment demonstrates a traversal of

a list to display its contents using an iterator - Note that you should avoid doing the following

things - Sending a mutator message, such as add, to the

backing list when an interator is active. - Sending the message remove to an iterator when

another iterator is open on the same backing list.

While (iter.hasNext()) System.out.println(ite

r.next())

114

13.3 Iterators

- A list iterator responds to messages specified in

the interface java.util.ListIterator. - This interface extends the Iterator interface

with several methods for navigation and modifying

the backing list. - Table 13-10 shows the additional navigational

methods

115

13.3 Iterators

- The additional mutator operations work at the

currently established position in the list (see

Table 13-11.)

116

13.3 Iterators

- Using a List Iterator

- In Table 13-12, we present a sequence of list

iterator operations and indicate the state of the

underlying list after each operation. - Remember that a list iterators current position

is located - before the first item,

- after the last item,

- or between two items.

- In the table, the current position is indicated

by a comma and by an integer variable called

current position.

117

13.3 Iterators

118

13.3 Iterators

119

13.3 Iterators

120

13.3 Iterators

121

13.3 Iterators

122

Lesson 14 Linear Collections Stacks and

Queues

123

Lesson 14 Linear Collections Stacks and Queues

- Objectives

- Understand the behavior of a stack and recognize

applications in which a stack would be useful. - Understand the behavior of a queue and recognize

applications in which a queue would be useful. - Understand the behavior of a priority queue and

recognize applications in which a priority queue

would be useful.

124

Lesson 14 Linear Collections Stacks and Queues

- Vocabulary

- activation record

- call stack

- front

- infix form

- pop

- postfix form

- priority queue

- push

- queue

- rear

- round-robin scheduling

- stack

- token

- top

125

14.1 Stacks

- Stacks are linear collections in which access is

completely restricted to just one end, called the

top. - The classical example is the stack of clean trays

found in every cafeteria. - Whenever a tray is needed, it is removed from the

top of the stack, and whenever clean ones come

back from the scullery, they are again placed on

the top. - Stacks are said to adhere to a last-in first-out

protocol (LIFO). - The last tray brought back from the scullery is

the first one taken by a customer.

126

14.1 Stacks

- The operations for putting items on and removing

items from a stack are called push and pop,

respectively. - Figure 14-1 shows a stack as it might appear at

various stages.

127

14.1 Stacks

128

14.1 Stacks

- The Stack Interface

- We provide our own Stack interface with the

implementing classes ArrayStack and LinkedStack,

along the lines of Java's List collections. - Our Stack interface, as shown in Table 14-1, is

fairly simple.

129

14.1 Stacks

130

14.1 Stacks

- A simple example illustrates the use of the Stack

interface and the class ArrayStack. - In this example, the items in a list are

transferred to the stack and then displayed. - Their display order is the reverse of their order

in the list

List lst new ArrayList() // Create list and

add objects .. put some objects into the

list Stack stk new ArrayStack() // Create

stack and transfer objects for (int i 0 i lt

lst.size() i) stk.push(lst.get(i)) while

(stk.size() gt 0) // Display objects from stack

System.out.println(stk.pop())

131

14.1 Stacks

- Applications of Stack

- Applications of stacks in computer science are

numerous. - Here are just a few

- Parsing expressions in context-free programming

languages-a problem in compiler design. - Translating infix expressions to postfix form and

evaluating postfix expressions.

132

14.1 Stacks

- Backtracking algorithms.

- Managing computer memory in support of method

calls-discussed later in the lesson. - Supporting the "undo" feature in

- text editors,

- word processors,

- spreadsheet programs,

- drawing programs,

- and similar applications.

- Maintaining a history of the links visited by a

Web browser.

133

14.1 Stacks

- Evaluating Arithmetic Expressions

- First, we transform an expression from its

familiar infix form to a postfix form, and then

we evaluate the postfix form. - In the infix form, each operator is located

between its operands. - In the postfix form, an operator immediately

follows its operands. - Table 14-2 gives several simple examples.

134

14.1 Stacks

135

14.1 Stacks

- EVALUATING POSTFIX EXPRESSIONS

- Evaluation is the simpler process and consists of

three steps - Scan across the expression from left to right.

- On encountering an operator, apply it to the two

preceding operands and replace all three by the

result. - Continue scanning until reaching the expression's

end, at which point only the expression's value

remains.

136

14.1 Stacks

- To express this procedure as a computer

algorithm, we use a stack of operands. - In the algorithm, the term token refers to either

an operand or an operator

create a new stack while there are more tokens in

the expression get the next token if the

token is an operand push the operand onto

the stack else if the token is an operator

pop the top two operands from the stack

use the operator to evaluate the two operands

just popped push the resulting operand onto

the stack end if end while return the value at

the top of the stack

137

14.1 Stacks

- The time complexity of the algorithm is O(n),

where n is the number of tokens in the

expression. - Table 14-3 shows a trace of the algorithm as it

is applies to the expression 4 5 6

3 -.

138

14.1 Stacks

139

14.1 Stacks

- TRANSFORMING INFIX TO POSTFIX

- In broad terms, the algorithm scans, from left to

right, a string containing an infix expression

and simultaneously builds a string containing the

equivalent postfix expression. - Operands are copied from the infix string to the

postfix string as soon as they are encountered. - However, operators must be held back on a stack

until operators of greater precedence have been

copied to the postfix string ahead of them.

140

14.1 Stacks

141

14.1 Stacks

142

14.1 Stacks

- Backtracking

- A backtracking algorithm begins in a predefined

starting state and then moves from state to state

in search of a desired ending state. - At any point along the way, when there is a

choice between several alternative states, the

algorithm picks one, possibly at random, and

continues. - If the algorithm reaches a state representing an

undesirable outcome, it backs up to the last

point at which there was an unexplored

alternative and tries it. - The algorithm either exhaustively searches all

states, or it reaches the desired ending state.

143

14.1 Stacks

- The role of a stack in the process is to remember

the alternative states that occur at each

juncture. - To be more precise

create an empty stack push the starting state

onto the stack while the stack is not empty

pop the stack and examine the state if the

state represents an ending state return

SUCCESSFUL CONCLUSION else if the state has

not been visited previously mark the state

as visited push onto the stack all

unvisited adjacent states end if end

while return UNSUCCESSFUL CONCLUSION

144

14.1 Stacks

- Suppose there are just five states, as shown in

Figure 14-2, with states 1 and 5 representing the

start and end, respectively. - Lines between states indicate adjacency.

- Starting in state 1, the algorithm proceeds to

state 4 and then to 3. - In state 3, the algorithm recognizes that all

adjacent states have been visited and resumes the

search in state 2, which leads directly to state

5 and the end.

145

14.1 Stacks

- Table 14-6 contains a detailed trace of the

algorithm.

146

14.1 Stacks

147

14.1 Stacks

148

14.1 Stacks

- Memory Management

- A Java compiler translates a Java program into

Java bytecodes. - A complex program called the Java Virtual Machine

(JVM) then executes these. - The memory, or run-time environment, controlled

by the JVM is divided into six regions, as shown

on the left side of Figure 14-3.

149

14.1 Stacks

150

14.1 Stacks

- Working up from the bottom, these regions

contain - The Java Virtual Machine, which executes a Java

program. - Bytecodes for all the methods of our program.

- The program's static variables.

- The call stack.

- Unused memory.

- The object heap.

151

14.1 Stacks

- Internal to the JVM are two variables, which we

call locationCounter and basePtr. - The locationCounter points at the instruction the

JVM will execute next. - The basePtr points at the top activation record's

base.

152

14.1 Stacks

- Every time a method is called, an activation

record is created and pushed onto the call stack.

- When a method finishes execution and returns

control to the method that called it, the

activation record is popped off the stack.

153

14.1 Stacks

- The activation records shown on the right side of

the figure contain two types of information. - The regions labeled Local Variables and

Parameters hold data needed by the executing

method. - The remaining regions hold data that allows the

JVM to pass control backward from the currently

executing method to the method that called it.

154

14.1 Stacks

- While a method is executing, local variables and

parameters in the activation record are

referenced by adding an offset to the basePtr. - Thus, no matter where an activation record is

located in memory, the local variables and

parameters can be accessed correctly provided the

basePtr has been initialized properly.

155

14.1 Stacks

- Just before returning, a method stores its return

value in the location labeled Return Value. - The value can be a reference to an object, or it

can be a primitive such as an integer or

character. - Because the return value always resides at the

bottom of the activation record, the calling

method knows exactly where to find it.

156

14.1 Stacks

- When a method has finished executing, the JVM

- Reestablishes the settings needed by the calling

method by restoring the values of the

locationCounter and the basePtr from values

stored in the activation record. - Pops the activation record from the call stack.

- Resumes execution of the calling method at the

location indicated by the locationCounter.

157

14.1 Stacks

- Implementing the Stack Classes

- Stacks are linear collections, so the natural

choices for implementations are based on arrays

and linked structures. - Instead of using these structures directly, we

use the ArrayList and LinkedList classes. - Following is the code for the class ArrayStack,

which uses an ArrayList

158

14.1 Stacks

import java.util.ArrayList public class

ArrayStack implements Stack private

ArrayList list public ArrayStack()

list new ArrayList() public Object

peekTop() if (list.isEmpty())

throw new IllegalStateException("Stack is

empty") return list.get(list.size() 1)

159

14.1 Stacks

public Object pop() if

(list.isEmpty()) throw new

IllegalStateException("Stack is empty")

return list.remove(list.size() 1)

public void push(Object obj)

list.add(obj) public int size()

return list.size()

160

14.2 The StringTokenizer Class

- Java provides a StringTokenizer class (from the

java.util package) that allows you to break a

string into individual tokens using either the

default delimiters (space, newline, tab, and

carriage return) or a programmer-specified

delimiter. - The process of obtaining tokens from a string

tokenizer is called scanning.

161

14.2 The StringTokenizer Class

- Table 14-7 shows several StringTokenizer methods.

162

14.2 The StringTokenizer Class

- For example, the following code displays each

word of a sentence on a separate line in the

terminal output stream

String sentence "Four score and seven years

ago, our forefathers set "

"forth this great nation." St