Atherosclerotic vascular disease - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 65

Title:

Atherosclerotic vascular disease

Description:

Atherosclerotic vascular disease AVD may manifest as: Coronary artery disease. Cerebrovascular disease. Peripheral vascular disease. Pathophysiology: – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:322

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Atherosclerotic vascular disease

1

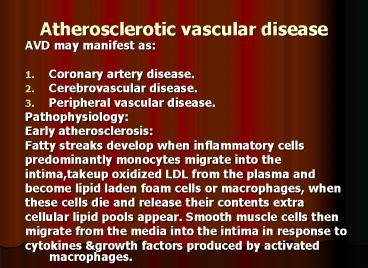

Atherosclerotic vascular disease

- AVD may manifest as

- Coronary artery disease.

- Cerebrovascular disease.

- Peripheral vascular disease.

- Pathophysiology

- Early atherosclerosis

- Fatty streaks develop when inflammatory cells

- predominantly monocytes migrate into the

- intima,takeup oxidized LDL from the plasma and

- become lipid laden foam cells or macrophages,

when - these cells die and release their contents extra

- cellular lipid pools appear. Smooth muscle cells

then - migrate from the media into the intima in

response to - cytokines growth factors produced by activated

macrophages.

2

- The lipid core will be covered by smooth muscle

cells and matrix, producing a stable

atherosclerotic plaque which is asymptomatic

until it becomes large enough to obstruct

arterial flow. - Advanced atherosclerosis

- In an established atherosclerotic plaque

macrophages mediate inflammation smooth muscle

cells promote repair, if inflammation

predominates, the plaque becomes active or

unstable may be complicated by ulceration

superadded thrombosis. Cytokines such as

interleukin-1, tumour necrosis-alpha, interferon

gamma, platelet derived growth factors, and

matrix metalloprotinases are released by

activated macrophages may cause the initial

smooth muscle

3

- Cells overlying the plaque to become senescent

resulting in thinning of the protective fibrous

cap, may lead to erosion, fissuring or rupture of

the plaque surface, exposing its content to

circulating blood, may trigger platelet

aggregation thrombosis, may cause partial or

complete obstruction resulting in infarction or

ischemia of the affected organ.

4

(No Transcript)

5

Risk Factors

- A. Fixed R. F

- Age

- Male sex

- Family history.

- B. Modifiable R.F

- Smoking - Sedentary lifestyle

- Hypertension - Obesity

- Lipid disoder. - Diet

- D.M

- Haemostatic variables

6

- Primary Prevention

- Population advice to prevent coronary disease

- Do not smoke.

- Take regular exercise (minimum of 20 minutes

three times a week). - Maintain ideal body weight .

- Eat a mixed diet rich in fresh fruit

vegetables. - Aim to get no more than 30 of energy intake from

saturated fat.

7

- Secondary prevention

- Patients who already have evidence of

atheromatous vascular disease e.g M.I, are at

high risk of another vascular event, can be

offered a variety of treatment and measures to

improve their outlook (secondary prevention). - Correction of risk factors

- Aspirin

- Beta blockers

- ACE Inhibitors

8

Coronary Heart Disease

- It is the most common form of heart disease.

- Most important cause of premature death.

- In UK 1 in 3 men 1 in 4 women die of CHD.

- Clinical manifestation

- Stable angina.

- Unstable angina.

- M.I

- Heart failure.

- Arrhythmia.

- Sudden death.

9

Stable angina

- Angina pectoris is caused by transient myocardial

ischemia. - It may occur whenever there is an imbalance

between myocardial oxygen supply demand. - Coronary atheroma is the most common cause.

- Other causes include aortic valve disease

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

10

- Clinical features

- The history is the most important factor in

making the diagnosis. - Central chest pain, discomfort or breathlessness

that is precipitated by exertion or other forms

of stress, (heavy meal, cold exposure, intense

emotion, lying flat/ decubitus, vivid dreams/

nocturnal angina), and relieved by rest. - Start up angina the pain comes when they start

walking that later it dose not return despite

greater effort. - Physical examination is frequently negative, but

should include - Evidence of valve disease, important risk

factors, left ventricular dysfunction, features

of arterial disease e.g carotid bruits and

untreated conditions that may exacerbate angina

e.g anemia, thyrotoxicosis.

11

- Investigations

- Resting ECG

- Evidence of previous M.I, but may be normal.

- Occasionally T wave flattening or inversion.

- The most important ECG changes is reversible ST

segment depression or elevation with or without T

wave inversion at the time the patient is

experiencing symptoms. - Exercise ECG

- Standard treadmill or bicycle ergometer protocol,

planar or down-sloping ST-segment depression of 1

mm or more is indicative of ischemia, up-sloping

is less specific often occurs in normal

individuals. - Exercise ECG is used to diagnose angina, assess

severity identifying high- risk individuals. - False ve Digoxin, LVH, LBBB, WPW syndrome, the

accuracy is lower in women than men.

12

(No Transcript)

13

(No Transcript)

14

(No Transcript)

15

- Risk stratification in stable

angina. - High Risk post infarct angina, poor effort

tolerance, ischemia at low workload, left main

or three vessel disease, poor LV function. - Low Risk

- Predictable exertional angina, good effort

tolerance, ischemia only at high workload,

single-vessel or minor two-vessel disease, good

LV function. - Other forms of stress testing

- Myocardial perfusion scanning useful when

exercise test is not diagnostic, or patient can

not exercise, its accuracy is higher than

exercise test. - The technique involve obtaining scintiscans of

the myocardium at rest and during stress after

administration of an i.v radioactive isotope e.g

thallium201, it is taken up by viable myocardium.

16

- A perfusion defect present during stress but not

rest indicates reversible myocardial ischemia,

whereas persistent perfusion defect indicates

previous M.I - Stress echocardiography

- It is alternative to perfusion scanning with

similar accuracy. - Uses transthoracic echo to identify ischemic

segments of myocardium area of infarction, the

latter do not contract at rest or during stress. - Coronary arteriography

- Shows the extent nature of coronary artery

disease, it may be indicated when other

investigations fail to diagnose the cause of

atypical chest pain.

17

(No Transcript)

18

- Management

- Assessment of the extent severity of arterial

disease. - Identification control of significant risk

factors - Measures to control symptoms.

- Identification of high risk patients

application of treatment to improve life

expectancy. - Antiplatelet therapy

- Aspirin 75-150 mg reduce the risk of MI,

Clopidogrel 75 mg daily equally effective but

more expensive can be used if the patient has

dyspepsia.

19

(No Transcript)

20

- Anti-anginal drugs

- Nitrates produces venous arteriolar dilatation

- Decrease myocardial oxygen demand (lower preload

afterload) increase myocardial oxygen supply. - Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), as aerosol

400 microgm or tablet 300-500 micro-gm

sublingually usually relieve angina in 2-3

minutes, side- effects include headache,

symptomatic hypotension syncope, the tablet

should be replaced 8 weeks after - the bottle has been opened.

- Nitrates can be used prophylactically before

exercise. - GTN is subject to extensive first pass metabolism

in the liver, its ineffeective when swallowed. - Nitrate free period of 6-8 hr. every day to avoid

tolerance.

21

- Preparation Peak action

Duration - Sublingual GTN 4-8

mins 10-30 mins - Buccal GTN 4-10

mins 30-300 mins - Transdermal GTN 1-3 hrs

up to 24 hrs - Oral isosorbide dinitrate 45-120 mins

2-6 hrs - Oral isosorbide mononitrate 45-120 mins

6-10 hrs

22

- Beta-blockers

- Reduce myocardial oxygen demand by reducing heart

rate, BP, and myocardial contractility. - Non-selective BB may exacerbate coronary spasm by

blocking Beta 2 coronary adrenoceptors. - Give once daily cardioselective preparation,

atenolol 50-100 mg daily, slow release metoprolol

200 mg daily, bisoprolol 5-10 mg daily. - ?ß should not be withdrawn suddenly as this may

cause arrhythmia, more angina or MI.(ßß

withdrawal syndrome). - Calcium antagonists

- lower myocardial oxygen demand by reducing blood

pressure and myocardial contractility. - Dihydropyridine calcium antagonists, such as

nifedipine and nicardipine, often cause a reflex

tachycardia it is often best to use these drugs

in combination with a ß-blocker. - In contrast, verapamil and diltiazem are

particularly suitable for patients who are not

receiving a ß-blocker because they inhibit

conduction through the AV node and tend to cause

a bradycardia or even atrioventricular block in

susceptible individuals.

23

- The calcium antagonists may reduce myocardial

contractility and can aggravate or precipitate

heart failure. Other unwanted effects include

peripheral oedema, flushing, headache and

dizziness. - Potassium channel activators

- This class of drug has arterial and venous

dilating properties but does not exhibit the

tolerance seen with nitrates. Nicorandil (10-30

mg 12-hourly orally) is the only drug in this

class currently available for clinical use. - it is conventional to start therapy with low-dose

aspirin, sublingual GTN and a ß-blocker, and then

add a calcium channel antagonist or a long-acting

nitrate later, if necessary.

24

- The goal is the control of angina with minimum

side-effects and the simplest possible drug

regimen. There is little or no evidence that

prescribing multiple anti-anginal drugs is of

benefit, and revascularisation should be

considered if an appropriate combination of two

drugs fails to achieve a symptomatic response. - Invasive treatment The most widely used invasive

options for the treatment of ischaemic heart

disease include percutaneous coronary

intervention (PCI including percutaneous

transluminal coronary angioplasty, PTCA) and

coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

25

- UNSTABLE ANGINA

- is a clinical syndrome that is characterised by

new-onset or rapidly worsening angina (crescendo

angina), angina on minimal exertion or angina at

rest. - The condition shares common pathophysiological

mechanisms with acute myocardial infarction, - the term 'acute coronary syndrome' is used to

describe these disorders collectively. - These entities comprise a spectrum of disease

that encompasses ischaemia with no myocardial

damage, ischaemia with minimal myocardial damage,

partial thickness (non-Q wave) myocardial

infarction, and full thickness (Q wave)

myocardial infarction .

26

- An acute coronary syndrome may present as a new

phenomenon or against a background of chronic

stable angina. - The culprit lesion is usually a complex ulcerated

or fissured atheromatous plaque with adherent

platelet-rich thrombus and local coronary artery

spasm . - Diagnosis and risk stratification

- The assessment of acute chest pain depends

heavily on an analysis of the character of the

pain and its associated features, evaluation of

the ECG, and serial measurements of biochemical

markers of cardiac damage, such as troponin I and

T.

27

- A 12-lead ECG is mandatory and is the most useful

method of initial triage. - Evolving transmural infarction is characterised

by persistent ST elevation, new Q waves or new

left bundle branch block - In patients with unstable angina or partial

thickness (non-Q wave or non-ST elevation)

myocardial infarction, the ECG may show ST/T wave

changes including ST depression, transient ST

elevation and T-wave inversion the T-wave

changes are sometimes prolonged. - Approximately 12 of patients with

well-characterised unstable angina or non-ST

segment elevation myocardial infarction progress

to acute infarction or death, and almost

one-third will suffer a recurrence of severe

ischaemic pain, within 6 months of the index

event.

28

- The risk markers that are indicative of an

adverse prognosis include - recurrent ischaemia,

- extensive ECG changes at rest or during pain,

- the release of biochemical markers (creatine

kinase or troponin), - arrhythmias and haemodynamic complications (e.g.

hypotension, mitral regurgitation) during

episodes of ischaemia - those who experience unstable angina following

acute myocardial infarction are also at increased

risk.

29

- Risk stratification is important because it

guides the use of more complex pharmacological

and interventional treatment .

30

- High risk

- Clinical

- Post-infarct anginaRecurrent pain at restHeart

failure - ECG

- ArrhythmiaST depressionTransient ST

elevationPersistent deep T-wave inversion - BiochemistryTroponin T gt 0.1 µg/l

31

- Low risk

- Clinical

- No history of MI

- Rapid resolution of symptoms

- ECG

- Minor or no ECG changes

- Biochemistry

- Troponin T lt 0.1 microgm/ l

32

- The initial treatment should include

- bed rest,

- antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 300 mg followed by

75-325 mg daily long-term and clopidogrel 300 mg

followed by 75 mg daily for 12 months, - anticoagulant therapy (e.g. unfractionated or

fractionated heparin) - ß-blocker (e.g. atenolol 50-100 mg daily or

metoprolol 50-100 mg 12-hourly - A dihydropyridine calcium antagonist (e.g.

nifedipine or amlodipine) can be added to the

ß-blocker, but may cause an unwanted tachycardia

if used alone verapamil or diltiazem is

therefore the calcium antagonist of choice if a

ß-blocker is contraindicated

33

- An intravenous infusion of unfractionated heparin

(with dose adjusted according to the activated

partial thromboplastin time) or weight-adjusted

subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (e.g.

enoxaparin 1 mg/kg 12-hourly) should be given - If pain persists or recurs, infusions of

intravenous nitrates (e.g. GTN 0.6-1.2 mg/hr or

isosorbide dinitrate 1-2 mg/hr) or buccal

nitrates may help, but such patients should also

be considered for early revascularisation. - Refractory cases or those with haemodynamic

compromise should be considered for a

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist (e.g.

abciximab, tirofiban or eptifibatide),

intra-aortic balloon pump or emergency coronary

angiography .

34

- Most low-risk patients stabilise with aspirin,

clopidogrel, heparin and anti-anginal therapy,

and can be gradually mobilised. If there are no

contraindications, - exercise testing may be performed prior to or

shortly following discharge. - Coronary angiography should be considered with a

view to revascularisation in all patients at

moderate or high risk, including those who fail

to settle on medical therapy, those with

extensive ECG changes, those with an elevated

plasma troponin and those with severe

pre-existing stable angina. - This often reveals disease that is amenable to

PCI however, if the lesions are not suitable

for PCI the patient should be considered for

urgent CABG.

35

(No Transcript)

36

- MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

- Myocardial infarction (MI) is almost always due

to the formation of occlusive thrombus at the

site of rupture or erosion of an atheromatous

plaque in a coronary artery. - The thrombus often undergoes spontaneous lysis

over the course of the next few days, although by

this time irreversible myocardial damage has

occurred. - Without treatment the infarct-related artery

remains permanently occluded in 30 of patients. - The process of infarction progresses over several

hours and therefore most patients present when it

is still possible to salvage myocardium and

improve outcome.

37

(No Transcript)

38

- CLINICAL FEATURES

- Pain is the cardinal symptom of MI, but

breathlessness, vomiting, and collapse or syncope

are common features. - The pain occurs in the same sites as angina but

is usually more severe and lasts longer - It is often described as a tightness, heaviness

or constriction in the chest. At its worst, the

pain is one of the most severe which can be

experienced and the patient's expression and

pallor may vividly convey the seriousness of the

situation - Most patients are breathless and in some this is

the only symptom. Indeed, some myocardial

infarcts pass unrecognised.

39

- Painless or 'silent' myocardial infarction is

particularly common in older or diabetic

patients. - If syncope occurs, it is usually due to an

arrhythmia or profound hypotension. Vomiting and

sinus bradycardia are often due to vagal

stimulation and are particularly common in

patients with inferior MI. - Nausea and vomiting may also be caused or

aggravated by opiates given for pain relief. - Sometimes infarction occurs in the absence of

physical signs. - Sudden death, from ventricular fibrillation or

asystole, may occur immediately, and many deaths

occur within the first hour.

40

- If the patient survives this most critical stage,

the liability to dangerous arrhythmias remains,

but diminishes as each hour goes by. - The development of cardiac failure reflects the

extent of myocardial damage and is the major

cause of death in those who survive the first few

hours of infarction.

41

- Physical signs

- Signs of sympathetic activation

- Pallor, sweating, tachycardia

- Signs of vagal activation

- Vomiting, bradycardia

- Signs of impaired myocardial function

- Hypotension, oliguria, cold peripheries

- Narrow pulse pressure

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Third heart sound

- Quiet first heart sound

- Diffuse apical impulse

- Lung crepitations

- Signs of tissue damage

- Fever

- Signs of complications, e.g. mitral

regurgitation, pericarditis

42

- INVESTIGATIONS

- Electrocardiography The ECG is usually helpful in

confirming the diagnosis however, it may be

difficult to interpret if there is bundle branch

block or evidence of previous MI. - Only rarely is the initial ECG entirely normal,

but in up to one-third of cases the initial ECG

changes may not be diagnostic. - The earliest ECG change is usually ST elevation

later on there is diminution in the size of the R

wave, and in transmural (full thickness)

infarction a Q wave begins to develop. - Subsequently, the T wave becomes inverted, this

change persists after the ST segment has returned

to normal.

43

- In contrast to transmural lesions, partial

thickness or subendocardial infarction causes

ST/T wave changes, without Q waves or prominent

ST elevation this is often accompanied by some

loss of the R waves in the leads facing the

infarct and is also known as non-Q wave or non-ST

elevation myocardial infarction. - The ECG changes are best seen in the leads that

'face' the infarcted area. - When there has been anteroseptal infarction,

abnormalities are found in one or more leads from

V1 to V4 - while anterolateral infarction produces changes

from V4 to V6, in aVL and in lead I.

44

- Inferior infarction is best shown in leads II,

III and aVF, while at the same time leads I, aVL

and the anterior chest leads may show

'reciprocal' changes of ST depression - Infarction of the posterior wall of the left

ventricle does not cause ST elevation or Q waves

in the standard leads, but can be diagnosed by

the presence of reciprocal changes (ST depression

and a tall R wave in leads V1-V4). - Some infarctions (especially inferior) also

involve the right ventricle this may be

identified by recording from additional leads

placed over the right precordium.

45

- The serial evolution of ECG changes in full

thickness myocardial infarction. A. Normal ECG

complex. B. Acute ST elevation ('the current

of injury'). C. Progressive loss of the R

wave, developing Q wave, resolution

of the ST elevation and terminal T wave

inversion. D. Deep Q wave and T wave

inversion. E. Old infarction

46

(No Transcript)

47

- Plasma biochemical markers

- The biochemical markers that are most widely used

in the detection of MI are creatine kinase (CK),

a more sensitive and cardiospecific isoform of

this enzyme (CK-MB), and the cardiospecific

proteins, troponins T and I - The troponins are also released, to a minor

degree, in unstable angina with minimal

myocardial damage Serial (usually daily)

estimations are particularly helpful because it

is the change in plasma concentrations of these

markers that is of diagnostic value.

48

- CK starts to rise at 4-6 hours, peaks at about 12

hours and falls to normal within 48-72 hours. - CK is also present in skeletal muscle, and a

modest rise in CK (but not CK-MB) may sometimes

be due to an intramuscular injection, vigorous

physical exercise or, in old people particularly,

a fall. - Defibrillation causes significant release of CK

but not CK-MB or troponins. The most sensitive

markers of myocardial cell damage are the cardiac

troponins T and I, which are released within 4-6

hours and remain elevated for up to 2 weeks. - Other blood tests A leucocytosis is usual,

reaching a peak on the first day. The erythrocyte

sedimentation rate (ESR) becomes raised and may

remain so for several days. C-reactive protein

(CRP) is also elevated in acute MI.

49

(No Transcript)

50

- Chest X-ray

- This may demonstrate pulmonary oedema that is not

evident on clinical examination The heart size

is often normal but there may be cardiomegaly due

to pre-existing myocardial damage. - Echocardiography

- This can be performed at the bedside and is a

very useful technique for assessing left and

right ventricular function and for detecting

important complications such as mural thrombus,

cardiac rupture, ventricular septal defect,

mitral regurgitation and pericardial effusion.

51

- EARLY MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

- Provide facilities for defibrillation

- Immediate measures

- High-flow oxygen

- I.v. access

- ECG monitoring

- 12-lead ECG

- I.v. analgesia (opiates) and antiemetic

- Aspirin 300 mg

52

- Reperfusion

- Primary PCI or thrombolysis

- Detect and manage acute complications

- Arrhythmias

- Ischaemia

- Heart failure

- Patients are usually managed in a dedicated

cardiac unit because this offers a convenient way

of concentrating the necessary expertise,

monitoring and resuscitation facilities. - If there are no complications, the patient can

be mobilised from the second day and discharged

from hospital on the fifth or sixth day.

53

- Analgesia

- Adequate analgesia is essential not only to

relieve severe distress, but also to lower

adrenergic drive and thereby reduce pulmonary and

systemic vascular resistance and susceptibility

to ventricular arrhythmias. - Intravenous opiates (initially morphine sulphate

5-10 mg or diamorphine 2.5-5 mg) and antiemetics

(initially metoclopramide 10 mg) should be

administered through an intravenous cannula.

54

- Acute reperfusion therapy

- Thrombolysis

- Coronary thrombolysis helps restore coronary

patency, preserves left ventricular function and

improves survival. - Successful thrombolysis leads to reperfusion with

relief of pain, resolution of acute ST elevation

and sometimes transient arrhythmias (e.g.

idioventricular rhythm). - The sooner the patient is treated, the better the

results will be any delay will only increase the

extent of myocardial damage-'minutes mean

muscle'.

55

- Clinical trials have shown that the appropriate

use of these drugs can reduce the hospital

mortality of myocardial infarction by 25-50 and

follow-up studies have demonstrated that this

survival advantage is maintained for at least 10

years. - The benefit is greatest in those patients who

receive treatment within the first few hours, and

choice of agent is less important than speed of

treatment. - Streptokinase, 1.5 million U in 100 ml of saline

given as an intravenous infusion over 1 hour, is

a widely used regimen. Streptokinase is antigenic

and occasionally causes serious allergic

manifestations. It may also cause hypotension,

which can often be managed by stopping the

infusion and restarting at

56

- slower rate.

- Circulating neutralising antibodies are formed

following treatment with streptokinase and may

persist for 5 years or more. - These antibodies can render subsequent infusions

of streptokinase ineffective so it is advisable

to use another non-antigenic agent if the patient

requires further thrombolysis in the future. - Alteplase (human tissue plasminogen activator or

tPA) is a genetically engineered drug that is not

antigenic and seldom causes hypotension. The

standard regimen is given over 90 minutes (bolus

dose of 15 mg, followed by 0.75 mg/kg body

weight, but not exceeding 50 mg, over 30 minutes

and then 0.5 mg/kg

57

- body weight, but not exceeding 35 mg, over 60

minutes). - There is evidence that tPA may produce better

survival rates than streptokinase, particularly

among high-risk patients (e.g. large anterior

infarct), but with a slightly higher risk of

intracerebral bleeding (10 per 1000 increased

survival, but 1 per 1000 more non-fatal stroke). - Newer-generation analogues of tPA have been

generated that have a longer plasma half-life and

can be given as an intravenous bolus. Large-scale

trial data have demonstrated that tenecteplase

(TNK) is as effective as alteplase at reducing

death and MI whilst conferring similar

intracerebral bleeding risks.

58

- Reteplase (rPA) is administered as a double bolus

and trial data indicate a similar outcome to that

achieved with alteplase, although some of the

bleeding risks appear slightly higher. The double

bolus administration may provide practical

advantages over the infusion of alteplase. - An overview of all the large randomised trials

confirms that thrombolytic therapy significantly

reduces short-term mortality in patients with

suspected MI if it is given within 12 hours of

the onset of symptoms and the ECG shows bundle

branch block or characteristic ST segment

elevation of greater than 1 mm in the limb leads

or 2 mm in the chest leads.

59

- Thrombolysis appears to be of little net benefit,

and may be harmful in other patient groups,

specifically those who present more than 12 hours

after the onset of symptoms and those with a

normal ECG or ST depression. - The major hazard of thrombolytic therapy is

bleeding.

60

- RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO THROMBOLYTIC

THERAPY (POTENTIAL CANDIDATES FOR PRIMARY

ANGIOPLASTY) - Active internal bleeding

- Previous subarachnoid or intracerebral

haemorrhage - Uncontrolled hypertension

- Recent surgery (within 1 month)

- Recent trauma (including traumatic resuscitation)

- High probability of active peptic ulcer

- Pregnancy

61

- Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

- In institutions that are able to offer rapid

access (within 3 hours) to a 24-hour catheter

laboratory service, percutaneous coronary

intervention is the treatment of choice. - In comparison to thrombolytic therapy, it is

associated with a 50 greater reduction in the

risk of death, recurrent myocardial infarction or

stroke.

62

- The widespread use of PCI has been limited by the

availability of the resources necessary to

achieve this highly specialized emergency

service. - As a consequence, intravenous thrombolytic

therapy remains the first-line reperfusion

treatment in many hospitals. - For some patients, thrombolytic therapy is

contraindicated or fails to achieve coronary

arterial reperfusion. Early emergency PCI (within

6 hours of symptom onset) may be considered under

such circumstances, particularly where there is

evidence of cardiogenic shock.

63

- Acute right

- Coronary art.

- Occlusion.

64

- Initial angio Filling defect

65

- Complete resolution of flow following insertion

of stent