Chapter 6: Printed Circuit Board Design - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Title:

Chapter 6: Printed Circuit Board Design

Description:

Chapter 6: Printed Circuit Board Design Example of a Printed Circuit Board front and back side The course material was developed in INSIGTH II, a project ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:531

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Chapter 6: Printed Circuit Board Design

1

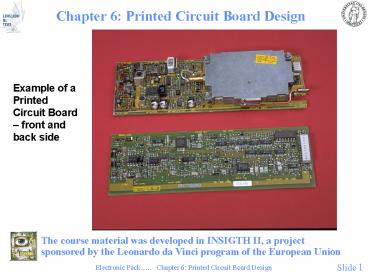

Chapter 6 Printed Circuit Board Design

- Example of a Printed Circuit Board front and

back side

The course material was developed in INSIGTH II,

a project sponsored by the Leonardo da Vinci

program of the European Union

2

PCB Design, Introduction

- For new electronic products, designers are key

persons, but should work in intimate cooperation

with - Sales, marketing and customers

- Subcontractors

- Production process experts

- Cost engineers

- Logistics and purchasing staff

- etc.

3

PCB Design, continued

- Advanced PCB CAD tools a neccessity

- Schematics

- Component Library

- Critical Parameters (Placement Constraints,

Electromagnetic Compatibility, Thermal

Limitations, etc) - Automatic Routing

- Final Touch Manual Routing

- (Verification by Final Simulation and Back

Annotation)

4

PCB CAD tools, continued

- Output

- Final Schematics

- Assembly Drawings

- Documentation for PWB Manufacturer (Gerber file

giving input for making PWB Manucturing Data (See

Chapter 5) - Data for Photo- or Laser Plotter for Making

Photographic Films and Printing Masks - Data for Numeric Drilling and Milling Machines

- Data for Placement Machines

- Data for Test Fixtures and Testing Machines

5

PCB Design, continued

- Guidelines for Right Quality

- Choice of Best Suited Technology/Technologies

- Choice of Components Right Compromise between

Performance, Reliability, Cost, etc. - Design for Production

- Design for Testability

- Design for Repair

6

PCB Design, continued

- Guidelines on Design for Manufacture

- Few layers

- Coarse pattern

- Standardisation

- Robust design (coarse tolerances)

- Orderly placement

Fig. 6.1.a Proper component placement for hole-

and surface mounted components

7

Orderly Placement, continued

- Fig. 6.1.b Proper component placement for hole-

and surface mounted IC components

8

PCB Design, continued

- Important Guideline for "Robust Design"

- Circuits should function with large parameter

tolerances - Design windows allowing for variations in

component parameters. - Process windows allowing for variations in each

process step. - Regulatory requirements on safety and EMC should

be passed within the specified design and process

windows.

9

Design of Hole and Surface Mounted PCBs Design

Parameters

- Minimum Dimensions

- The conductor cross section areas and resistivity

of the material determine maximum current

capacity and thereby minimum dimensions. - Current capacity is limited by excessive heating

of the conductors and the PCB. - Maximum allowed ohmic voltage drop along the

conductor also determines minimum dimensions.

10

Design Parameters Minimum Dimensions

- Fig. 6.2 Current capacity and temperature

increase in conductors on PCBs.The upper figure

shows the temperature increase (labels on each

curve) at different combinations of

cross-sections and currents). The lower figure

shows the conductor cross-section (along the

x-axis) as a function of the conductor width for

different Cu-layer thicknesses.

11

Design Parameters DC Line Resistance

- DC Line resistanceR r L/(t b) r 2 .0

10 -8 Wm for Cu foil - r is resistivity of the conductor material (ohm

m) - L is conductor length

- t is conductor thickness

- b is conductor width

- Sheet Resistance ohm/square

- Rsq r / t

- R Rsq L / b

- 18 um copper Rsq 1 mW/sq

- 35 um copper Rsq 0.5 mW/sq

L

b

t

Current I

L

r/

R R

R

t

b

12

Hole and Surface Mounted PCB Design

- Pattern Minimum Dimensions

Table 6.1 Examples of minimum dimension and PCB

classes. The class indicates how many conductors

can pass between the solder pads of a DIP package

(no. of channels), and typical corresponding

minimum dimensions in mm. When two figures are

given for hole diameters, they are for component-

and via holes respectively.

13

Pattern Minimum Dimensions,continued

a)

b)

- Fig. 6.4 a) Parameters in layout dimensions

used in Table 6.1. b) Minimum dimensions for

solder mask for surface mount PWBs. Left

Dimensions for screen printed solder mask, with

one common opening for all solder lands of an IC

package. Right Photoprocessible solder mask with

a "pocket" for each terminal, permitting

conductors between the solder lands.

14

Mixed Hole Mount and SMD Printed Circuit Boards

- Mixed PCBs are quite common due to

- Technical issues

- Component availability and cost

- Available capacity and performance of equipment

in PCB manufacturing line(s).

Fig. 6.5 Common types of SMD- and mixed

SMD-/hole mount PCBs.

15

SMD Printed Circuit Boards

- Important aspects of design

- Component heat tolerances for reflow-/wave solder

processes - Component orientation for wave solder

- Shadowing

- Solder thieves for wave soldering

- Minimum distance between components

- Isolated via holes/solder lands

Fig. 6.6 Preferred and not preferred directions

of SMD components during wave soldering.

16

Important Aspects of Design, continued

- Fig. 6.7 Minimum separation between SMD

components during wave soldering.

17

Important Aspects of Design, continued

- Fig. 6.8 Solder lands for SMD components should

be separated from heavy copper areas by narrow

constrictions. Conductors should preferably leave

the solder lands of one component symmetrically.

18

Important Aspects of Design, continued

- Fig. 6.9 Via holes should be separated from

solder lands.

19

Important Aspects of Design, continued

- Fig. 6.10 Dummy land for better control of the

amount of adhesive in wave soldering process.

20

Important Aspects of Design, cont..

- Fig. 6.11 "Solder thieves" are areas in the Cu

layer to reduce bridging in wave soldering.

Placed as the last area exposed to the solder wave

21

Important Aspects of Design, continued

- Fig. 6.12 Parameters defining solder land

dimensions for SMD resistors and capacitors,

please refer to Table 6.2.

22

Solder Land Dimensions

- Table 6.2 Solder land dimensions for SMD

resistors and capacitors (mm), please refer to

Figure 6.12.

23

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Fig. 6.13 Additional dimensions of SMD component

and solder lands. Width a a Wmax K

Length b Reflow b Hmax 2Tmax K

Wave b Hmax 2Tmax 2K Length B B Lmax

2Hmax 2Tmax K, K 0.25 mm.

24

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Fig. 6.14 Solder land dimensions for SMD

transistors and diodes.

25

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Table 6.3 Solder land dimensions for SO or VSO

components (mm), please refer to Figure 6.15.

Fig. 6.15 Solder land dimensions for SO and VSO

packages, please refer to Table 6.3.

26

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Fig. 6.16 Solder land dimensions for PLCC, LLCC

and flatpacks, please refer to Tables 6.4 - 6.7. - a Bmax 0.1 mm B width of leas

- b Fmax 0.4 mm F length of lead footprint

- A,B Emax 0.8 mm E separation between lead

ends

27

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Table 6.4 Solder land dimensions for PLCC (mm),

please refer to Figure 6.16. Pitch, P 1.27

(0.050") a 0.63 b 2.0

Table 6.5 Solder land dimensions for LLCC (mm),

please refer to Figure 6.16. Pitch, P 1.27

(0.050") a 0.63 b 2.5

28

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Table 6.6 Solder land dimensions for flatpacks

(mm), please refer to Figure 6.16. b 2.5

29

Solder Land Dimensions, continued

- Fig. 6.17 Solder land dimensions for TAB.

30

Design for Testability

- Fig. 6.18 a) Correct position of test point,

separated from solder land. b) Test points on

solder lands are not recommended. c) Testing

on components or component leads should be

avoided.

31

Design for Testability, continued

- Fig. 6.19 Examples of test point placement on a

grid with 0.1 spacing, for testing of SMD

components with 0.05 pitch.

32

Testability

- Defect level

- DL (ppm) 1 - Y(1-T) x 106

- DL defect level

- Y yield

- T fault coverage (One cannot test all failure

modes) - Test Methods

- Functional test (Test the PCB in the system PCB

OK or not) - In-circuit test (Test at local test points

finds the exact fault) - Scan path (For logic circuits digital output

versus input) - Boundary scan (Scan path with separate test pins)

- Built-in self test (Add test circuitry on the PCB)

33

Test Principles

- Guidelines for Test Strategy for In-circuit test

- Single sided (normally) - double sided test

fixtures are expensive and less robust - Separate test points - avoid using component

leads or solder lands - 0.1" grid (normally) - 0.05 test probes are

fragile (0.1" is 2.5mm) - Solder on test points for reliable contact

- Watch out and consider possible problems with

high component - Modern equipment often uses flying

probesExample on YouTubehttp//www.youtube.com

/watch?vsj5yDyWw67w

34

Material Considerations for Thermal Compatibility

- Fig. 6.20 Mechanical strain is caused by

difference in coefficient of thermal expansion

(TCE), and changes in temperature. The magnitude

of the corresponding stress depends on

dimensions, temperature difference/change, and

the elastic moduli of the materials.

35

Thermal Design

- Electronic components can dissipate a lot of

heat! - You can use your PC for cooking some chips

are rated for more than 100 degrees C

From Vevin Skadron, Un of Virginia

36

Thermal Design

- Fig. 6.21 a) Heat flow from hole mounted and

surface mounted components on a PCB. b)

Relative amount of heat removed by conduction,

convection and radiation, from DIP hole mounted

components and SMD LLCC components - typical

values.

37

Thermal Design

- Fouriers law

- Q DT/RT

- RT (1/K) (L/A)

- Q Heat flow W

- DT Temperature difference C

- RT Thermal resistance C/W

- K Thermal conductivity W/mC

- L,A Length / cross-section

- Equivalent to Ohms law

- I DU/Rel

- Rel 1/s L/A

- Convection Q h A DT

- h convection coefficient W/m oC

Fig. 6.22 a) Heat flow due to conduction -

Fouriers equation. b) Heat flow due to

convection.

38

Thermal Design, continued

- Thermal Resistance

- Rjc Thermal resistance junction - case

- Rjl Thermal resistance junction - lead

- Rja Thermal resistance junction - ambient

- Tj Ta P Rja

- Ta Ambient temperature

- Tj Junction temperature

Fig. 6.23 Thermal model of an IC and package.

39

Thermal Design, continued

- Example IBMs Thermal Module for Mainframe

Logics

40

Thermal Design, continued

- Table 6.8 Typical thermal resistances for

various package types oC/W

41

Thermal Design, continued

- Table 6.9 Typical values for the effective

thermal conductivity of different types of PCBs.

42

Thermal Design, continued

- Effective Thermal Conductivity in PCBs

- Keff S (kiti) / ttot

- ki thermal conductivity layer i

- ti thickness layer i

- ttot total thickness

43

Thermal Design, continued

- Design of Right Thermal Coefficient of Expansion

(TCE) - a S ( ai Ei ti ) / S ( Ei ti )

- ti thickness of layer i

- ai TCE material in layer i

- Ei Elastic modulus of layer i

Table 6.10 Material parameters for calculating

TCE and effective thermal conductivity of metal

core boards.

DET TAS FORBEHOLD OM ENDRINGER

44

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.24 Cross section and thicknesses for a

practical PWB with two Cu/Invar/Cu cores. The

thicknesses were designed to get an over-all TCE

of 7.5 ppm/C m The achieved value was

measured to be 9.3 ppm/C m Calculated

effective thermal conductivity in the x - y

directions was 21 W/ C m

45

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.25 a) Pin-grid package with cooling

fins. b) Measured thermal resistance in the

component with forced air cooling.

46

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.26 LLCC package with thermal solder lands

and thermal vias connected to a metal core in the

PCB.

47

Thermal Design, continued

- Improved Cooling

- Thermal vias

- Cooling fins

- Fan

- Thermally conducting gas helium, fluorocarbon

- Liquid water, fluorocarbon, oil

- Boiling liquid

- Heat pipe

- Impingement cooling/Microbellows

- Microgrooves

48

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.27 a) Forced air convection in a

channel between two PCBs (Texas Instruments) - b) Water-cooled heat exchanger for edge cooling

of PCBs and temperature distribution

(qualitative).

49

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.28 Heat convection coefficient in

different cooling media for natural convection,

forced convection and boiling

50

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.29 "Microbellows cooling" A jet of water

or other cooling liquid impinges on the backside

of the chip. The bellow structure is necessary to

accommodate thermal expansion

51

Thermal Design, continued

- Fig. 6.30 Cooling by forcing liquid through

microscopic, etched channels in the semiconductor

chip 6.32. The channels are approximately 400

µm deep and 100 µm wide.

52

Thermal Simulation

- Fig. 6.31 Bar diagram for calculated

temperatures on each component chip by the

thermal simulation program TMOD.

53

Thermal Simulation

- Heat dissipation and heat transfer simulations.

From Toshiba

54

High Frequency Design

- When needed?

- tr lt 2.5 tf

- tr 10 - 90 rise time

- tf l/v

- tr is 10-90 rise time

- tf is time-of-flight-delay over the length l of

critical conductor paths of the circuit - v is propagation speed v c/?er

- c speed of light (3x10E8 m/sec ?30cm/ns)

- er effective relative dielectric constant

55

(No Transcript)

56

Main board 1995 66MHz, 2002 333 MZ

57

3GIO 3rd Generation I/O PCI Express

In MHz

58

High Frequency Design

- Fig. 6.32 Distributed parameters in a model of a

loss free transmission line. C and L are

capacitance and inductance per m length.

59

Lossy transmission line

- Resistive power loss

- R the resistance along the line (per meter)

- L the inductance along the line (per meter)

- G the conductance shunting the line (per meter)

- C the capacitance shunting the line (per meter)

- Series components are the sum of both signal and

ground.

60

High Frequency Design

- Table 6.11 Signal propagation speed in different

media. v c0/(Öer) 30 (cm/ns)/Öer

61

Loss less line

- Homogenous and loss less transmission line

- Telegraphers equation

- At high frequencies the transmission line losses

on printed circuit boards in digital systems can

be neglected -gt homogenous - Parameters

- Distance to ground (power) plane(s)

- Geometry of conductor and dielectric around

- Additive / Subtractive process give different

geometry - Influence of delamination (air)

- Frequency dependent dielectric properties

62

High Frequency Design, cont

- Characteristic Impedance

- V ZoI

- Zo characteristic impedance

- Zo ((R jwL)/(G jwC))1/2

- w angular frequency

- R resistance per unit length

- L inductance per unit length

- C capacitance per unit length

- G loss conductance per unit length

- In loss free medium

- Zo ?(L/C)

- Reflection coefficient

- R (Z1 - Z2)/(Z1 Z2)

- Z1 and Z2 characteristic impedances of media 1

and 2

63

Propagation speed, v

- Dependent on electrical properties

- Derived from the material properties of the

medium (Maxwell equations) - Homogenous lossless transmission line in a

uniform dielectric medium - mr 1 for all non-magnetic materialsm is

magnetic permeability

64

Delay

- Concerns

- Synchronisation

- Clock Screw

- simultaneous is relative

- Causes

- Rise / fall time of component (driver)

- Physical distance

- Time of flight delay

- From one end of the line to the other (loss less

line)

Propagation speed (Co30cm/ns) Dielectric

?r (cm/nsec) Polyimid 2,5 -

3,5 16 - 19 Silicon dioxide 3,9

15 Epoxy glass (PCB) 4,2 - 5,0

13 Alumina (ceramic) 9,5 10

65

Reflections

- Fig. 6.34 Distorted signal as a function of

time when the transmitter has 78 ohms impedance

the same as the characteristic impedance and the

receiver has different impedances as indicated.

If the receiver also has 78 ohms impedance the

signal at the receiver is a time delayed replica

of the transmitted signal. - If RLZ0, transmission line behave as it was

infinitely long, hence no reflection

66

Termination of line reflections

- Terminate by

- Characteristic line impedance

- A 50 mismatch is acceptable

- However termination gives

- Higher power dissipation

- Which needs a higher driver capability

- Different techniques for adjust termination to

the driver capability, next slide

- It should be noted that if a reflection does

occur, and propagates back to the driver

(source), it can reflect again off the source.

The driver has an output impedance. If that

output impedance is exactly equal to Zo, then

there will be no further reflection from the

source. But if the output impedance of the driver

is different than Zo, an additional reflection

will occur. The magnitude of that reflection is

again determined by a reflection coefficient.

67

Termination possibilities

68

Reflections from other discontinuities

- In a typical PCB the characteristic impedance of

the x and y wiring planes are not identical.

(anisotrop media) - Connection via forms a small inductive and

capacitive discontinuity - Other

- Connectors

- Corners and turns of the copper line

- Do not use 90 turns

- Pins of IC packages

- Capacitors and terminating resistors

69

Obtaining a controlled impedance

- Fig. 6.35 Geometries for obtaining a controlled

characteristic impedance. - See pages 6.38 and 6.39 for equations and

examples

70

High Frequency Design, continued

- Fig. 6.36 Expressions for characteristic

impedance, Zo, signal propagation speed, TPD,

capacitance per unit length, Co, and crosstalk,

XTalk, in different geometries a) coaxial, b)

microstrip c) stripline. The expression for

coaxial geometry is exact, the others are

approximate and valid only in certain parameter

ranges.

71

High Frequency Design, continued

- Fig. 6.37 Dependence of the characteristic

impedance on geometric dimensions, for a)

Striplineb) Microstrip. w is the signal

conductor width, S is the distance between ground

planes for stripline, and H the distance between

signal conductor and ground plane for microstrip

(please refer to Figure 6.35). Curves are shown

for different signal conductor thicknesses, t.

a

b

72

Cross talk

- Cross talk is the capacitive and inductive

coupling of signals from one signal line to

another - Increases with board density and performance

(frequency and current drive) - Distance to ground (power) plane

- Smaller conductor spacing

- Dielectric constant

- Larger currents

- Rise and fall times

- Current drive

- Near End Crosstalk or reverse crosstalk If we

measure the crosstalk in the sample line at the

same end of the cable we inserted the signal, it

is called near end or reverse/backward crosstalk. - Far End Crosstalk or forward crosstalk If we

measure the crosstalk in the sample line at the

opposite end of the cable that we inserted the

signal, it is called far end or forward crosstalk

73

High Frequency Design, continued

- Fig. 6.38 Cross talk A signal from A to C is

transmitted to the B - D line and gives noise in

B (backward or near end cross talk) and in D

(forward or far end cross talk).

74

Cross talk

- Cross talk A signal from A to B is transmitted

to the C - D line and gives noise in C (reverse

or near end cross talk) and in D (forward or far

end cross talk).

75

Forward cross-talk

76

Reverse cross-talk

77

High Frequency Design, continued

- Fig. 6.39 Backward cross talk as a function of

conductor separation in stripline geometry in

different dielectrics. The effect increases with

increasing er and decreases with increasing

conductor separation.

78

Minimize cross-talk

- Use maximum allowable spacing between signal

lines - Use low dielectrics materials

- Minimize spacing between signal and ground lines

/ plane - Isolate clocks and critical signals form other

lines with larger line spacing or isolate with

ground lines - Use twisted pair for sensitive signals (clock,

reset, set, clear) - When using ribbon cable make every other line a

ground line (e.g. U-ATA (UDMA hard disk cable) - Terminate signals lines into characteristic

impedance, use low impedance drivers

79

Attenuation

- Vb Va exp(-al)

- a Attenuation coefficient

- a (ar, as ) ad

- ar dominates at low frequencies

- as at high frequencies (GHz)

- ar R / (2Zo)

- as (p mr mo f r)1/2 / (w Zo) for skin depth

ds (r / p f mr mo)1/2 ltlt t - ad p (eoe)1/2 f tan d/ c

- R ohmic resistance per unit length

- r electrical DC resistivity in the conductor

- t conductor thickness

- tan d dielectric loss tangent

- w conductor width

- f frequency and m mr mo magnetic

permeability

80

Skin depth

- With an alternating current, however, there is a

delay in the magnetic field's response to the

change in current and the 'old' magnetic field

tends to push the current towards the outside of

the conductor. As the frequency increases, so

does the effect until at very high frequencies

the entire current flows in a very narrow skin on

the conductor--hence the name. - Skin depth is due to the circulating eddy

currents (arising from a changing H field)

cancelling the current flow in the center of a

conductor and reinforcing it in the skin.

81

Attenuation, continued

- Fig. 6.40 High frequency skin depth for copper,

and conductor resistance due to skin effect,

relative to the DC resistance. The resistance

has increased by approx. a factor 2 when the skin

depth d is one half of the conductor thickness t.

82

Attenuation, continued

- Fig. 6.41 Conductor- and dielectric losses as

functions of frequency for multilayer thin film

modules.

83

Figure 1, run once with a 4-mil-wide trace (red

eye diagram) and once with 8-mil (yellow). The

wider trace has less skin-effect loss, and

therefore better signal quality as indicated by

the more-open eye. Eye opening Space between 1

and 0 See http//bwrc.eecs.berkeley.edu/classes/

icdesign/ee290c_s11/lectures/Lecture02_Link_Over_E

nviron_6up.pdf

Same simulation as in Figure 1's better eye, run

once with a typical FR-4 dielectric (loss tangent

0.02 yellow eye diagram) and once with a

low-loss dielectric (loss tangent 0.004

purple). The low-loss material makes a

substantial improvement to the eye opening, but

would result in a much costlier PCB.

84

Ground bounce

- Wirebonds, package pins and PCB routing acts as

inductances at high frequency - Induced voltage/noise bounce VLL(dI/dt)

- Good practice

- Lower rise times

- Lower output drive

- Use ground and power plane

- Use bypass capacitors for power

- Minimize power/ground tracks (use plane)

- Use vias wisely (vias acts as a inductance)

85

Power distribution

- Simultaneous switching gives large current spikes

- High capacitance ? Keeps stable voltage levels

- Low inductance ? makes L dI/dt switching noise

low - Power distribution is also modelled as

transmission lines - Reduced supply voltage ? reduced signal to noise

86

Practical

- Use ground - power planes

- Reference planes for signal lines

- Better dynamic power distribution

- Time of flight

- High packaging density

- Cross talk

- Large separation between signal lines

- Want a high impedance from the driver circuit

point of view I U/Z - However High impedance ltgt Low packaging

density - Manufacturing tolerances

- Line width, homogeneity

87

EMC - Electromagnetic compliance

- International rules for

- Radiation of electromagnetic energy

- Functionality of device in an electromagnetic

field (environment) - Noise interference with other equipment

- Immunity against external radiation

- Design with respect to EMC/EMI from the start

88

EMC - Design of circuit

- Wires and current loops acts as antennas

- Good PCB design

- Ground and power planes

- Shielding

- Basic design rules

- Ground plane

- Compact design

- Reduced current loops

- Minimum clock frequency

- Components with as long rise / fall time as

possible - Decoupling capacitors

- Shielding

- Star topology

- Metal case

- LSots opening

89

SPICE simulations

- High speed simulation difficult

- Not accurate models

- Stray capacitance and inductance

- Skin effect

- Cross talk

- Power supply

- Radiant effects will need wave simulation

FEM,FEA,TLM - No model will represent the absolute truth

90

Software simulation at Ghz

- GREATER HIGH FREQUENCY CAUSE CONCERNS

- As Wave-lengths reduce to package pattern

dimensions (_at_ 5 GHz , l/10 5 mm), each trace

becomes a radiating antenna - Radiated energy signal loss

- Radiated energy interference on other electric

conductors - Radiated energy increased EMC problems

- Radiated energy damage to living organisms

- Alternative means of conduction will have to be

used, when these factors become dangerous - Shielded conductors (conductor surrounded by

Ground conductor) - Wave-guides

- Light strands

- Full-wave Analysis becomes absolutely necessary

91

Measurements on high speed circuits

- Probe coupling

- Probe impedance 8-100pF parallel with 1-10M?

- Very important to include with resonance

circuits, as capacitance/inductance alters

resonant frequency - Impedance matching

- Short ground lead

- Remember common ground on scope

- If possible use 50? input

92

Design of Flexible Printed Circuits

- Fig. 6.42 Bending of double layer flexible print

with different conductor layout. The Figure shows

the number of cycles before failure with 5, 10

and 20 mm bending radius and 180 angel of

bending. (Data Schoeller Elektronik). If the

copper layer in the bending zone is strained 16

or more it is likely to fail during the first

cycle.

93

Design of Flexible Printed Circuits, continued

a)

c)

b)

- Fig. 6.43 a) Solder lands on flexible prints

should be rounded in order to reduce the

possibility for failures, b) The contour of the

board should be rounded in order to reduce

possibilities for tearing (dimensions in inches).

The "rabbit ears" on the ends of the metal foil

is for obtaining better adhesion to the

polyimide. c) Plastic rivets should be used to

avoid sharp bends in the interface between the

flexible and the rigid parts of the PCB.

94

Design of Membrane Switch Panels

- Fig. 6.44 Detail of a membrane switch panel. The

tail with interconnections to the panel is

protected with a laminated foil. Light emitting

diodes may be attached with conductive adhesive.

Screen printed polymer thick film series

resistors may be used.

95

Design of Membrane Switch Panels

- Fig. 6.45 Contact areas of membrane switch panel

with back lighting and window. Examples of

lighted text on a dark background and the

opposite combination. If a metal dome is used the

information has to be next to the key and not

underneath it.

96

System Level Modelling

- Fig. 6.46 The SUSPENS model for the different

levels in an electronic system. The symbols are

parameters characterising the system and

different technologies of the system. They are

quantified and used to compare or optimise

different possible versions of the system in

computer calculations. - VHDL is also used.

97

End of Chapter 6 Printed Circuit Board Design

- Important issues

- When designing PCBs

- Working with the right people including marketing

and production people - Working with the best tools

- Use good Design Guidelines and do not violate

Design Parameters - Robust design to allow for process variations

- Use solder land dimension templates

- Design for test

- Specific design methods for applications with

specific requirements - High speed, high power etc.

- Questions and discussions?