Methods, cont' PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 1

Title: Methods, cont'

1

A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the

influence of instant-release metformin on

response to clomiphene citrate and time to

conception in polycystic ovary syndromeWilliams

CD1, Pastore LM2, Shelly W2, Bailey AP2, Baras

D2, Bateman B11 Reproductive Medicine Surgery

Center of Virginia, PLC, Charlottesville, VA, 2

Department of Obstetrics Gynecology, University

of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

- Methods, cont.

- Mid-luteal progesterone was measured, and the

patient was considered ovulatory with a level

5ng/mL. However, CC was increased by 50mg to a

maximum dose of 200mg until optimal ovulation was

documented by a progesterone level gt15ng/mL. - Once optimally ovulatory, subjects remained in

treatment arm until conception or up to 6 cycles.

Subjects who did not become optimally ovulatory

on 200mg CC were unblinded. CC P subjects were

allowed to cross-over to CC M. CC M subjects

were withdrawn from further study after 6 cycles. - With positive pregnancy test, an ultrasound was

performed between 6-7 weeks at which time

metformin or placebo was discontinued. - Statistical Analyses

- Univariate analyses Student-t, Wilcoxon rank

sum, survival methods, and log rank tests

Background Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is

the most common endocrine disorder of

reproductive age women and is the most common

endocrine cause of infertility (Dunaif 92). 1

In some studies, adding metformin to CC has

been shown to improve ovulation rates in PCOS

patients who are resistant to CC (Nestler 98,

Vandermolen 01) but in other studies, no benefit

was demonstrated (Legro 07, Moll 06). 2,3,4,5

It has been postulated that the use of

extended-release metformin may not be as

efficacious in women with PCOS (Legro 07).

4 The investigators hypothesized that starting

instant-release metformin concurrently with CC

would improve ovulatory response and reduce the

time to conception compared to the use of CC

alone.

- References

- Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine F, Merriam GR,

eds. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cambridge

Blackwell Scientific, 1992. - Zawedzki JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for

polycystic ovary syndrome towards a rational

approach. In Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine F,

Merriam GR, eds. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

Cambridge Blackwell Scientific, 1992 377-84. - Franks S. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The New

England Journal of Medicine 1995 333(13)

853-861. - Fauser BC. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic

criteria and long-term health risks related to

polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The Rotterdam

ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop

group. Human Reproduction 2004 19(1) 41-47. - Legro R, Finegood D, Dunaif A. A fasting glucose

to insulin ratio is a useful measure of insulin

sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary

syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and

Metabolism 1998 83(8) 2694-2698. - Dahlgren E, Johansson S, Lindstedt G, et al.

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome wedge

resected in 1956 to 1965 a long-term follow-up

focusing on natural history and circulating

hormones. Fertility and Sterility 1992 57(3)

505-513. - Freedman DS, Jacobsen SJ, Barboriak JJ,

Sobocinski KA, Anderson AJ, Kissebah AH, et al.

Body fat distribution and male/female differences

in lipids and lipoproteins. Circulation 1990

81(5) 1498-1506. - Dahlgren E, Janson PO, Johansson S, et al.

Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for myocardial

infarction evaluated from a risk factor model

based on a prospective population study of women.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1992 71 599-604. - Hartz AJ, Rupley DC, Rimm AA. The association of

girth measurements with disease in 32,856 women.

American Journal of Epidemiology 1984 119(1)

71-80. - Haffner SM, Fong D, Hazuda HP, Pugh JA, Patterson

JK. Hyperinsulinemia, upper body adiposity, and

cardiovascular risk factors in non-diabetics.

Metabolism 1988 37(4) 338-345. - Schapira DV, Kumar NB, Lyman GH, Cox CE.

Abdominal obesity and breast cancer risk. Annals

of Internal Medicine 1990 112(3) 182-186. - Sellers TA, Kushi LH, Potter JD, Kaye SA, Nelson

CL, McGovern PG, et al. Effect of family

history, body fat distribution, and reproductive

factors on the risk of postmenopausal breast

cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 1992

326(20) 1323-1329. - Lapidus L, Helgesson O, Merck C, Bjorntorp P.

Adipose tissue distribution and female

carcinomas. A 12-year follow-up of participants

in the population study of women in Gothenburg,

Sweden. International Journal of Obesity 198812

361-368. - Schapira DV, Kumar NB, Lyman GH, Cavanagh D,

Roberts WS, LaPolla J. Upper-body fat

distribution and endometrial cancer risk. Journal

of the American Medical Association 1991

266(13) 1808-1811. - Regan L, Owen EJ, Jacobs HS. Hypersecretion of

luteinising hormone, infertility, and

miscarriage. Lancet 1990 336 1141-1144. - Homburg R, Armar NA, Eshel A, Adams J, Jacobs HS.

Influence of serum luteinising hormone

concentrations on ovulation, conception, and

early pregnancy loss in polycystic ovary

syndrome. British Medical Journal 1988 297

1024-1026. - Watson H, Kiddy DS, Hamilton-Fairley D, et al.

Human Reproduction 1993 8(6) 829-833. - Knudsen UB, Hansen V, Juul S, Secher NJ.

Prognosis of a new pregnancy following previous

spontaneous abortions. European Journal of

Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology

1991 39 31-36.

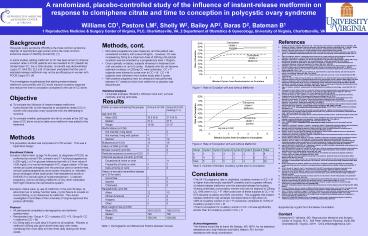

Figure 1. Rate of Ovulation with and without

Metformin

- Objective

- To evaluate the influence of instant-release

metforrmin hydrochloride (M) on the response to

clomiphene citrate (CC) in women with polycystic

ovary syndrome who are attempting to conceive. - To evaluate whether participants who fail to

ovulate at the 200 mg dose of CC alone would

ovulate once metformin was added to the

treatment. - Methods

- The population studied was comprised of n55

women. This was a triple-blind design. - Enrollment Criteria

- Inclusion criteria were a) age 18-45 years, b)

diagnosis of PCOS, as confirmed by normal TSH,

prolactin and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (lt200

ng/dL) a 2-hr glucose tolerance test with a

2-hour value of lt200 mg/dL or a normal hemoglobin

A1C oligoovulation (gt35 day menstrual cycles

averaged over the previous year) or amenorrhea

clinical hyperandrogenemia (acne and/or

hirsutism) or elevated serum androgen levels

(total and/or free testosterone levels or DHEAS)

if no clinical signs of hyperandrogenism , c)

desired pregnancy, and d) not taking metformin or

any other medication that might influence the

reproductive system. - Exclusion criteria were a) use of metformin in

the prior 60 days, b) abnormal liver or kidney

function tests, c) prior failure to ovulate on

clomid 200mg, or d) intolerance to metformin. The

Human Investigation Committee of the University

of Virginia approved this protocol (10268). - Protocol

- All participants completed a demographics and

behavior questionnaire. - Randomized into Group A- CC placebo (CC P),

Group B- CC metformin (CC M) - CC 50mg daily on cycle days 5-9 given to all

subjects. Placebo or metformin 500mg was given

three times daily with meals, increasing from

once-daily to three times daily dosing over three

weeks.

Results

Figure 2. Rate of Conception with and without

Metformin

Table 2. Number of blinded, ovulatory cycles

prior to conception

Conclusions

- The 54.1 pregnancy rate in unblinded, ovulatory

women on CC M is higher than previously

reported34, possibly due to a greater efficacy of

instant-release metformin over the

extended-release formulation. - Among unblinded, nonovulatory women who did not

respond to 200mg CC, 64 were in CC P. After

cross-over of these subjects to CC M, 67

became ovulatory and 50 conceived. This

suggests that instant-release metformin may

sensitize nonresponders to high-dose CC. - 40 of ovulatory women in CC P conceived,

compared to 70.6 of ovulatory women in CC M. - Time to conception for ovulatory women in CC M

was significantly shorter than for ovulatory

women in CC P. - Acknowledgements

- The Authors would like to thank Mir Siadaty, MD,

MPH, for his statistical assistance and Jody

Halloran and Kathy Watson, RN, for their

assistance with study coordination.

Table 1. Demographic and Behavioral Factors

between Groups