Architecture - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 11

Title:

Architecture

Description:

Light is the mystic element that glitters ... All of the figures ... Times Arial Calibri Eurostile Title & Bullets PowerPoint Presentation PowerPoint ... – PowerPoint PPT presentation

Number of Views:82

Avg rating:3.0/5.0

Title: Architecture

1

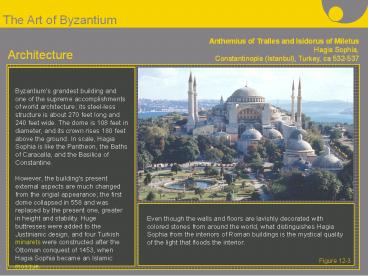

The Art of Byzantium

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of

Miletus Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul),

Turkey, ca 532-537

Architecture

Byzantium's grandest building and one of the

supreme accomplishments of world architecture

its steel-less structure is about 270 feet long

and 240 feet wide. The dome is 108 feet in

diameter, and its crown rises 180 feet above the

ground. In scale, Hagia Sophia is like the

Pantheon, the Baths of Caracalla, and the

Basilica of Constantine. However, the

building's present external aspects are much

changed from the origial appearance the first

dome collapsed in 558 and was replaced by the

present one, greater in height and stability.

Huge buttresses were added to the Justinianic

design, and four Turkish minarets were

constructed after the Ottoman conquest of 1453,

when Hagia Sophia became an Islamic mosque.

Even though the walls and floors are lavishly

decorated with colored stones from around the

world, what distinguishes Hagia Sophia from the

interiors of Roman buildings is the mystical

quality of the light that floods the interior.

Figure 12-3

2

The Art of Byzantium

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of

Miletus Hagia Sophia Constantinople (Istanbul),

Turkey, ca 532-537

Architecture

The canopy-like dome that also dominates the

inside of the church rides on a halo of light

from windows in the dome's base. The forty

windows create the illusion that the dome is

resting on the light that comes through

them--like a "floating dome of heaven." Huge

wall piers to the north, half-domes to the east

and west, and smaller domes covering columned

niches give a curving flow to the design. The

"walls" in Hagia Sophia indicate that the

architects sought Roman monumentality as an

effect, but did not design according to Roman

principles.

The use of brick instead of concrete was a

further departure from Roman practice and

characterized Byzantine architecture as a

distinctive style.

Figure 12-3

3

The Art of Byzantium

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of

Miletus Hagia Sophia Constantinople (Istanbul),

Turkey, ca 532-537

Architecture

The architects were ahead of their time in that

they used pendentives to transfer the weight from

the dome to the piers beneath, rather to the

walls. In this, the space beneath the dome was

unobstructed and allowed room for windows in the

walls, which created the illusion of the

suspended dome. This technicality can be

explained by experts today, but was a mystery to

Anthemius' and Isidorus' contemporaries in the

6th century. Additionally, the fusion of two

independent architectural traditions the

vertically oriented central-plan building and the

horizontally oriented basilica was previously

unseen, and was the successful conclusion to

centuries of experimentation.

Figure 12-3

4

The Art of Byzantium

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of

Miletus Hagia Sophia Constantinople (Istanbul),

Turkey, ca 532-537

Architecture

The mystical quality of the light that floods the

interior has fascinated visitors for centuries.

The canopy-like dome that also dominates the

inside of the church rides on a halo of light

from windows in the dome's base. The forty

windows create the illusion that the dome is

resting on the light that comes through

them--like a "floating dome of heaven." Thus,

Hagia Sophia has a vastness of space shot through

with light and a central dome that appears to be

supported by the light it admits. Light is the

mystic element that glitters in the mosaics,

shines from the marbles, and pervades spaces that

cannot be defined. It seems to dissolve material

substance and transform it into an abstract

spiritual vision.

Figure 12-3

5

The Art of Byzantium

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of

Miletus Hagia Sophia Constantinople (Istanbul),

Turkey, ca 532-537

Architecture

The poet Paulus described the vaulting as covered

with "gilded tesserae from which a glittering

stream of golden rays pours abundantly and

strikes men's eyes with irresistible force. It is

as if one were gazing at the midday sun in

spring." The use of the gilded mosaics serves

to create a more radiant light when the sun hits

it the light is more complex and

multidimensional and creates a different aura

than if the light had just hit a plain

mosaic. The gilded mosaic changes the color of

the light to a softer, more ethereal realm that

lends itself to the atmosphere of Hagia Sophia.

Figure 12-3

6

The Art of Byzantium

Justinian, Bishop Maxanius and attendants,

mosaic from the north wall of the apse, San

Vitale, Ravenna, italy, ca. 547

Mosaics

The golden wreath of victory Christ extends

during the Second Coming to Saint Vitalis is also

extended to Justinian, for he appears on the

Savior's right side in the dependent mosaic below

and to the left of the apse mosaic. These rites

confirmed and sanctified his rule, combining the

political and the religious. The laws of the

Eastern Church and the laws of the state, united

in the laws of God, were manifest in the person

of the emperor and in his God-given right.

Justinian is distinguished from those around

him, not only by his royal purple, but by his

halo, another indication of his god-like status.

Each figure's position in the mosaic is

important. Justinian, in the center, is

distingushed by his holy halo. He seems to be

behind bishop to the right, and with the imperial

powers to the left, yet his bowl is in front of

the bishop, unifying the two groups of people.

Figure 12-10

7

The Art of Byzantium

Justinian, Bishop Maxanius and attendants,

mosaic from the north wall of the apse, San

Vitale, Ravenna, italy, ca. 547

Mosaics

All of the figures are rigid in stature but the

objects everyone is holding to the right gives it

the sense of slow motion. Their feet seem to

float on the ground like divine powers and they

all have blank stares and simple charactersitics.

Iconography of religion is used for these

figures instead of veristic expression.

Figure 12-10

8

The Art of Byzantium

Theodora and attendants, mosaic from the south

wall of the apse, San Vitale, Ravenna, italy,

ca. 547

Mosaics

The empress stands in state beneath an imperial

canopy, waiting to follow the emperor'

procession. An attendant beckons her to pass

through the curtained doorway. The fact she is

outside the sanctuary in a courtyard with a

fountain and only about to enter attests that, in

the ceremonial protocol, her rank was not quite

equal to her consort's. It is interesting in

that neither she, nor Justinian ever visited

Ravenna, where they are shown in the mosaic.

Theodora's portrayal is more surprising and

testifies to her unique position in Justinian's

court.

Theodora's prominent role in the mosaic is proof

of the power she wielded at Constantinople and,

by extension, at Ravenna. In fact, the

representation of the Three Magi on the border of

her robe suggests she belongs in the elevated

company of the three monarchs who approached the

newborn Jesus bearing gifts.

Figure 12-11

9

The Art of Byzantium

Theadora and attendants, mosaic from the south

wall of the apse, San Vitale, Ravenna, italy,

ca. 547

Mosaics

Again, the figures are elongated, with bent

elbows. The faces are all facing forward, and the

eyes of the prominent figures are looking towards

the viewers. The hands of the major figures in

the mosaic are across their heart, and all of the

poses are very regal and stiff, upright. The

dimension of the mosaic is flat and there is very

little attempt at portraying objects and people

in some type of perspective.

Key word to use when describing the mosaics on

the walls of San Vitale Elongated, spiritual,

ethereal, votive eyes, religiously symbolic,

denatured

Figure 12-11

10

The Art of Byzantium

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child, icon (Vladimir

Virgin), tempera on wood, Late 11th to Early

12th Century

Mosaics

The Vladimir Virgin clearly reveals the stylized

abstraction that centuries of working and

reworking the conventional image had

wrought. The characteristic traits of the

Byzantine icon of the Virgin and Child are all

present the sharp sidewise inclination of the

Virgin's head to meet the tightly embraced Christ

Child the long, straight nose and small mouth

the golden rays in the infant's drapery the

decorative sweep of the unbroken contour that

encloses the two figures the flat silhouette

against the golden ground and the deep pathos of

the Virgin's expression as she contemplates the

future sacrifice of her son.

The icon of Vladimir was placed before or above

stairs in churches or private chapels, and

incense and smoke from candles that burned

blackened its surface.

Figure 12-29

11

The Art of Byzantium

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child, icon (Vladimir

Virgin), tempera on wood, Late 11th to Early

12th Century

Mosaics

It was exported to Russia in the early twelfth

century and then taken to Moscow to protect the

city. The Russians believed that the Vladimir

icon saved the city of Kazan from later Tartar

invasions and all of Russia from the Poles in the

seventeenth century. It is a historical symbol

of Byzantium's religious and cultural mission to

the Slavic world. These types of images were not

universally accepted by Christians. Those who

opposed the use of icons are termed

iconoclasts and those who embrace the concept of

the icon are known as iconphiles

The following passage from Exodus 204,5 explains

the reason behind the iconclast ideal Thou

shalt not make unto thee any graven image or any

likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or

that is in the earth beneath, or this is in the

water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down

thyself to them, nor serve them

Figure 12-29