Next Discussion Session PowerPoint PPT Presentation

1 / 52

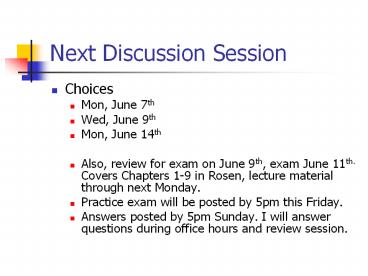

Title: Next Discussion Session

1

Next Discussion Session

- Choices

- Mon, June 7th

- Wed, June 9th

- Mon, June 14th

- Also, review for exam on June 9th, exam June

11th. Covers Chapters 1-9 in Rosen, lecture

material through next Monday. - Practice exam will be posted by 5pm this Friday.

- Answers posted by 5pm Sunday. I will answer

questions during office hours and review session.

2

Special Interest Groups

- Recall from last time Community/Group voting

pressure. People are more likely to vote if they

are part of a group that actively encourages

voting (ie. unions) - Further, these people tend to vote the same way

(unions traditionally vote Democratic in the USA) - This implies that these groups exercise a level

of power that individual voters cannot. As such,

there is an incentive to form special interest

groups.

3

Special Interest Groups (SIGs)

- SIG members generally share a common trait. SIGs

generally form to encourage politicians to make

policy decisions that benefit the shared

interests of their members. - Example NRA and gun control.

4

What are these common traits?

- Level of income people at different income

levels may have different ideas on what programs

to fund. - Industry of Employment Unions, Firm Owners

- Region People in the breadbasket (Kansas,

Oklahoma, etc) have preferences for the level of

farm subsidies - Personal Characteristics AARP, religious groups,

ethnic groups, even gender.

5

Lobbyists

- SIGs may hire lobbyists to meet with

politicians. These lobbyists may attempt to

provide information (could it be biased?) on the

state of the world, or they may attempt to offer

campaign contributions or bribes in exchange for

favors.

6

SIGs continued

- These groups may engage in rent-seeking behavior,

in order to win favorable outcomes for their

members. It is to be noted that SIGs with

opposing interests may be operating at the same

time in the same legislative body - Tobacco lobbyists spend millions each year

attempting to limit the level of cigarette taxes

imposed by states. - Non-smoker rights groups spend millions each

year trying to promote healthier lifestyles

through banning public smoking and raising

cigarette taxes.

7

Who are some of the big SIGs?

- National Rifle Association (NRA) a group that

seeks to protect the constitutional right to bear

arms. Outspoken opponents of gun control. Pay for

pro 2nd amendment publications, lobby, organize

congressional letter campaigns. Members receive

discounts at hotels such as Best Western and

Ramada, rental car companies Hertz and Avis. 4.3

million members.

8

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD)

- Group dedicated to ending drunk-driving through

legislative and grassroots action, and

victim-counseling. 47 million dollars of funding

in the 2002-2003 fiscal year. Frequently called

to testify before congressional subcommittees.

Instrumental in helping legislators propose and

enact tougher drunk-driving legislation, etc.

9

Chapter 7 Conceptual Issues in Income

Redistribution

10

Introduction

- Will provide framework for thinking about the

normative and positive aspects of government

income redistribution policy.

11

Introduction

- Some questions whether economists should be

concerned with distributional issues. - Value judgments embodied in the right income

distribution. - No scientific basis for the right distribution.

12

Introduction

- Focus on efficiency alone has problems.

- That focus, too, is a value judgment.

- Multiple equilbria.

- Decision makers do care about the income

distribution economic analysis ineffective if it

doesnt consider this policy-maker constraint.

13

Distribution of Income

- Can analyze household income, and see how equally

or unequally the pie is distributed. - Table 7.1 shows the percentage of money income

among households for more than 30 years.

14

Table 7.1

15

Distribution of Income

- Richest 20 receives about 50 of total income.

- Poorest 20 receives about 4 of total income.

- Inequality has increased over time.

16

Are the rich getting richer and the poor getting

poorer?

- Most of you have heard this at some point or

another. - Half true. The rich are getting richer. But the

poor are also getting richer. - Inequality is increasing because the rich are

getting more as a of income, relative to the

poor. - Note that using our current definition of the

poverty line, almost everyone in the US would

have been below the line in 1880. Economists

predict that almost nobody will be below this

line in the year 2090.

17

Distribution of IncomePoverty

- The poverty line is a fixed level of real income

which is considered enough to provide a minimally

adequate standard of living. - Inherently arbitrary, but still a useful

benchmark. - Trends over time

- Differences across groups

18

Quick digression on the poverty line

- Created in 1965 by Mollie Orshansky for the SSA.

- Based on food requirements. Dept. of Ag. (1955)

found that poor families spend 1/3 income on

food. Orshansky estimated the cost of providing a

basic level of nutrition and multiplied by 3. - Note poverty line increases with size of family,

but at a decreasing rate (due to the belief that

there are certain fixed costs in households)

19

Absolute vs. Relative poverty lines

- Some debate as to whether or not our poverty line

is appropriate. - Poor families now spend about 1/5 income on food.

- Others have proposed relative poverty lines.

Victor Fuchs (1967) proposed setting the line at

45-50 of the median households income. - US still uses a version of Orshanskys poverty

line.

20

Distribution of IncomePoverty

- Poverty line for a family of 4 was 18,244 in

2001. - Median household income more than double that,

42,228. - Table 7.2 shows poverty rates for selected groups

in 2001.

21

Table 7.2

22

Distribution of IncomePoverty

- Poverty rates in U.S. in 2001 might be considered

surprisingly high 11.7 for population as

whole. - Concentrated among certain groups, such as female

headed households, children, and minorities. - Elderly have lower poverty rates than the U.S.

average.

23

Distribution of IncomePoverty

- Can also look at trends over time.

- See Table 7.3

- Poverty considerably lower than in 1960s, but

not much progress since 1970.

24

Table 7.3

25

Interpretation Problems

- Poverty line ( poverty rate) is subject to a

number of criticisms. - When interpreting the numbers, it is useful to

know the conventions and limitations.

26

Interpretation Problem 1

- Income consists only of cash receipts.

- Excludes in-kind transfers like health insurance,

food stamps, and housing. - Would reduce poverty rate by more than 20.

- Excludes non-market work such as childcare or

housework. - Ignores income flow from durable goods.

27

Interpretation Problem 2

- Income is before-tax.

- It ignores cash refunds from the Earned Income

Tax Credit, which has grown dramatically in the

last decade, and now amounts to more than 31

billion annually. - Ignoring this overstates poverty rates, and also

affects the trends over time.

28

Interpretation Problem 3

- Income is measured annually.

- Not obvious what the correct time frame should

be. - Income does fluctuate from year-to-year.

- Lifetime income considerations seem relevant.

- Consider a starving college student, for

example. Not really poor in a lifetime sense.

29

Interpretation Problem 4

- Unit of observation

- Person, family, household?

- People often make decisions as an economic unit,

and there are economies of scale in household

production. - Classifications can matter for poverty numbers

- Bauman (1997) calculates that including the

income of non-family members (such as nonmarried

cohabitors) would reclassify 55 of people who

are poor out of official definition.

30

Upshot

- It is quite likely that the official poverty rate

is overstated. - This is not to say that there is no real reason

for income distribution. - Also, just because ones family is officially

above the poverty line isnt to say his family is

doing well for itself. A family of 4 with 19,000

annual income is still in some sense struggling.

31

Rationales for Income Redistribution

- Different kinds of social welfare functions

- Utilitarian

- Maximin criterion (Rawlsian)

- Pareto efficient

- Non-individualistic

32

Simple Utilitarianism

- The utilitarian social welfare function is

- Which depends on all n members of society. One

specific function form is

- This special case is referred to as an additive

social welfare function.

33

Simple Utilitarianism

- With the additive SWF that was given, also

assume - Identical utility functions that depend only on

income - Diminishing marginal utility of income

- Societys total income is fixed

- Implication government should redistribute to

obtain complete equality.

34

Simple Utilitarianism

- This can be illustrated with 2 people.

- See Figure 7.1

- Any income level other than I does not maximize

the SWF. - I entails equal incomes.

35

Figure 7.1

36

Numerical Example

- 2 identical individuals (Betty and Al),

diminishing marginal utility of income. 40 in

economy. - Additive social welfare function

- For example. If Al has 30 dollars and Betty has

10, Social welfare W 21 9 30. - Total Utility is maximized when each individual

receives 20. W 1616 32.

37

Simple Utilitarianism

- Striking result is that full income equality

should be pursued, but some scrutiny required. - Assumes identical utilities

- Assumes decreasing marginal utility

- Assumes total income fixed

- E.g., no disincentives from this kind of

redistributive policy.

38

The Maximin Criterion

- The Rawlsian social welfare function is

- Social welfare in this case depends only on the

utility of the person who has the lowest utility. - Rawls (1971) asserts it has ethical validity

because of the notion of original position. - Notion that ex-ante individuals do not know where

in the income distribution they will be.

39

Original Position

- Rawls proposed a thought experiment

- Individuals start from a position of knowing

nothing about themselves. - They then choose how to organize society.

- The Maximin criterion is what Rawls believes

people would choose for themselves.

40

The Maximin Criterion

- These ethical claims are controversial

- Still selfish view in original position

- Individuals extremely risk averse here

- All that is relevant is the welfare of the

worst-off person, even if a policy is extremely

detrimental to everyone else.

41

Pareto Efficient Income Redistribution as

Justification for Income Redistribution

- Suppose that utility of richer person does depend

on poorer persons utility. That is

- Government redistribution in this case could

improve efficiency. It may be difficult for the

private market to do this, if, for example, the

rich lack information on just who really is poor. - Simply an externality problem.

42

Pareto Efficient Income Redistribution

- Altruism plays a role in this example, but

private market could conceivably give charity. - But not just altruism. Self-interest could play

a role. Suppose there is a possibility that, for

circumstances beyond your control, you become

poor. - When well-off, pay premiums. When bad times

hit, collect payoff. - Motivation of some social insurance programs.

43

Nonindividualistic views

- In previous cases, social welfare derived from

individuals utilities. - Some specify what the income distribution should

look like independent of individual preferences. - One example commodity egalitarianism.

- Right to vote, food, shelter, education, perhaps

health insurance.

44

Processes versus Outcomes

- All the above examples are concerned with

outcomes of distribution (who ends up with what) - Some argue that a just distribution of income is

defined by the process that generated it. - For example, equal opportunity in U.S.

- Ensuing outcome would be considered fair,

regardless of the income distribution it happened

to entail. - Fair bit of income mobility (Gottschalk, 1997).

- Does raise problem of how to evaluate social

processes.

45

Expenditure Incidence- the impact of expenditure

policy on distribution of real income

- Relative Price Effects

- Public Goods

- Valuing In-Kind Transfers

46

Relative Price Effects

- Suppose government subsidized housing of the

poor. - As a first pass, redistribution from rich to

poor. - May have overall effects on housing prices

- Landlords may reap part of gain.

- Affects wages of construction workers

- Generally, any government program sets off a

chain of price changes, and the incidence is

unclear.

47

Public Goods

- Do rich and poor benefits similarly from the

provision of public goods? - Difficult to measure, sensitive to assumptions

that are made.

48

Valuing in-kind transfers

- Government provides many benefits to the poor

in-kind that is, direct provision of goods

rather than cash. - Food stamps

- Medicaid

- Public Housing

- Estimating value is difficult. Not always valued

at dollar-for-dollar (if resale is difficult).

49

Valuing in-kind transfers

- Consider how the provision of an in-kind benefit

changes the budget constraint in transparency. - In this case, giving an in-kind benefit lowers

utility relative to an equally costly cash

transfer. - Although the person is better off by having the

in-kind transfer than not having it, she would be

even happier with the cash transfer.

50

Valuing in-kind transfers

- A person can never be made better off with an

in-kind transfer that is equal in cost to a cash

transfer. - There are instances, however, when a person is

indifferent between the two transfer schemes. - See overhead.

51

Valuing in-kind transfers

- Why give in-kind transfers if they tend to be

inefficient? - Commodity egalitarianism/ tax-payer sovereignty.

Congress (or taxpayers) may only want to provide

health-care or housing, rather than just give

cash. - May reduce welfare fraud (especially if the

in-kind transfer is an inferior good) - Politically viable because they help the producer

of the in-kind good.

52

Recap of Income Redistribution Conceptual Issues

- Distribution of income

- Poverty line

- Social welfare functions

- Valuing In-Kind transfers